Eating Disorders

False Food Allergy and Intolerance in Eating Disorders

Alternative testing for food intolerance and the risk of eating disorders.

Posted November 8, 2020

Food allergy and anaphylaxis are an increasing burden on citizens in developed countries. Prevalence is high in young children, but recent evidence indicates that they are becoming increasingly more common in teenagers and young women and, also, in developing countries.

However, the number of people who call themselves "allergic to food" is highly overestimated for the misuse of the term "allergic," which leads to defining allergic the undesirable effects of drugs, toxic reactions to food, enzymatic deficits (e.g., lactase or sucrase-isomaltose deficiency) and vasomotor reactions to irritants (e.g., citrus or tomato).

A further overestimation comes from attributing a food allergy to extremely different diseases (e.g., migraine, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic urticaria, chronic fatigue syndrome, child hyperkinetic syndrome, serum-negative arthritis, serous otitis, Crohn's disease) without the support of rigorous research. This has created a widespread general opinion that food allergy may be the "medical chameleon" potentially able to explain different disorders and symptoms without an identified specific biomarker.

Generally, there is a notable difference between the prevalence of clinical suspicion to an adverse reaction to food (about 20%) and diagnostic confirmation (1.8%) with the double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (considered as the gold standard in the diagnosis of food allergy) vs placebo.

Alternative food intolerance tests

An additional and worrying source of diagnostic confusion is the phenomenon of increasingly frequent use by the population of alternative diagnostic tests (see Table below), without any scientific validity. These tests are often recommended by health personnel (e.g., pharmacists, doctors, and homeopath biologists) who should identify, with methods different from traditional ones, the foods responsible for food allergies or food "intolerances." The latter term, which in its strictest sense indicates "any reproducible adverse reaction following the ingestion of a food or some of its components (proteins, carbohydrates, fats, preservatives) which includes toxic, metabolic and allergic reactions,” is increasingly used also to indicate a psychological aversion to different foods, as happens in a subgroup of patients with eating disorders.

Table: Some "alternative" tests used to assess food intolerances, none of which have robust evidence to validate the use:

- Cytotoxic test (Bryan test)

- Provocation/neutralization sublingual or subcutaneous test

- Biorisonance

- Electro-acupuncture

- Hair analysis

- Immunological tests (immunocomplex or specific food IgG)

- Applied kinesiology

- Cardio-auricular reflex test

- Pulse test

- Vega test

- Sarm test

- Biostrengt tests and variants

- Natrix or FIT 184 Tests

- BAFF (activating factor B lymphocytes) and PAF (platelet-activating factor) tests

False eating intolerances and eating disorders

Alternative testing for food intolerance is often misused in patients with eating disorders, particularly in those suffering from functional gastrointestinal symptoms. The hypothesis behind the use of alternative tests is that the targeted elimination of certain foods, to which the individual is "intolerant," produces an improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms and thus promotes the restoration of a regular diet.

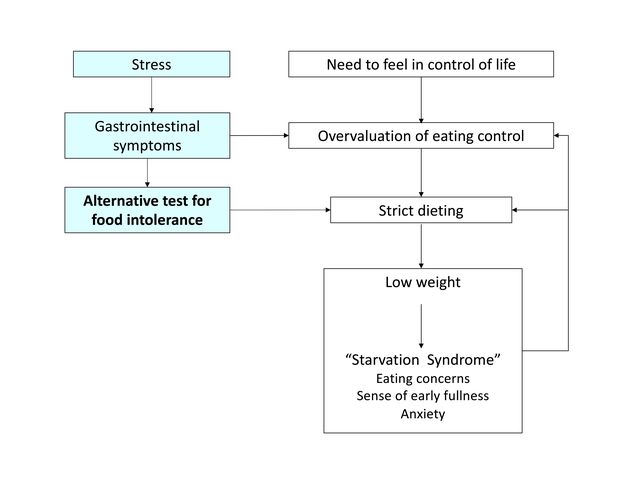

An account, confirmed by numerous clinical cases that my team has followed in recent years, described cases of anorexia nervosa developed in individuals who followed the dietary indications of alternative tests. The reported cases were young, normal-weight women who complained of vague gastrointestinal symptoms in the absence of documented organic damage. We have hypothesized that the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms in these people was triggered by stressful factors and not by intolerance to specific foods. The mediation factor between stress and dyspeptic symptoms could be the corticotropin release hormone that, at least in patients with irritable bowel syndrome, seems to act centrally modulating both motility and gastrointestinal symptoms.

The risk of developing an eating disorder following the prescription of a diet, which involves the elimination of several foods to reduce dyspeptic symptoms, seems particularly high in adolescents and young women who have a need to feel in control in life (e.g., feeling in control in various aspects life such as school, work, sports or other interests). Indeed, following a strict diet may trigger the shift toward the control of eating for two main reasons:

- Eating control is experienced as a successful behavior in the context of perceived failure in other areas of life.

- Reducing caloric intake and foods such as fermentation-producing carbohydrates often results in a short-term improvement of gastrointestinal symptoms.

However, gastrointestinal symptoms, after a short period of improvement, tend to worsen for the combined action of various mechanisms operating simultaneously, such as paying excessive attention to abdominal sensations that are not normally noted, and the negative effects of dietary restriction and weight loss on gastric emptying. These factors, associated with the overvaluation of eating control and morbid fear that the introduction of "intolerant" foods may exacerbate gastrointestinal symptoms maintain and intensify the eating-disorder psychopathology (Figure).

Diets that require the elimination of several foods, such as those suggested by alternative tests of food intolerance, also seem to be a trigger and maintenance mechanism of binge-eating episodes. Indeed, the attempt to limit food intake, regardless of whether it produces an energy deficit, requires the adoption of extreme and rigid dietary rules. The (almost inevitable) breaking of these rules is often interpreted as evidence of lack of self-control, resulting in temporary abandonment of the eating control and the intake of a large amount of food. The binge-eating episode, in turn, intensifies the concern about eating, shape, and weight and their control, which encourages further dietary restriction, resulting in an increased risk of a new binge-eating episode.

Treatment

In patients with an eating disorder who report a food intolerance, I refer them to an allergologist who, in most cases does not confirm the presence of any food intolerance. This correct diagnosis can help the patient to start a psychological evidence-based treatment such as enhanced cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders. This treatment helps the patients to gradually introduce avoided foods and regain weight (if indicated) and to develop a more articulate and non-predominant self-evaluation scheme based on the control of eating.

References

Woods RK, Stoney RM, Raven J, Walters EH, Abramson M, Thien FC. Reported adverse food reactions overestimate true food allergy in the community. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56(1):31-6. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601306

Senna G, Bonadonna P, Schiappoli M, Leo G, Lombardi C, Passalacqua G. Pattern of use and diagnostic value of complementary/alternative tests for adverse reactions to food. Allergy. 2005;60(9):1216-7. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00875.x

Dalle Grave R, Calugi S. Cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2020.