Dementia

Still Alice? Still Alzheimer’s

Searching for good news and grace in the tragedy of dementia

Posted July 31, 2015

“Who can take us seriously when we are so far from who we once were? Our strange behavior and fumbled sentences change others’ perceptions of us and our perceptions of ourselves. We become ridiculous, incapable, comic… but this is not who we are. This is our disease and like any disease, it has a cause, it has a progression, and it could have a cure.”

— Alice Howland, Still Alice

Earlier this year, Julianne Moore won the Academy Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role for her portrayal of Alice Howland, the protagonist of the film adaptation of Lisa Genova’s novel Still Alice, about a linguistics professor who develops early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Moore’s performance showed us the struggle of woman whose identity was rooted in a love of language as her memory and verbal skills were lost to a literal tangle of neurons gone awry. The film itself brought some welcome light, and life, to the tragedy of dementia, an illness that that will probably affect all of us at some point (whether personally or through a family member), yet is often left undiscussed.

We don’t like to discuss dementia for the same reason we don’t like to talk about death. Because despite the implied meaning of the title Still Alice, the reality is that dementia is a kind of death, a gradual death of the mind in which the very essence of ourselves is eroded while our bodies go on living. And despite all that we’ve learned about dementia through scientific discovery through the years – which is quite a lot – we haven’t really made a lot of progress in terms of treatment. And so, following the adage “if you can’t say anything nice about some[thing], don’t say anything at all,” there really isn’t a lot to say about dementia. At least not until its inevitability strikes close to home and something has to be said.

If we are to talk about dementia, we should start with some of the impressive but sobering discoveries that have emerged from scientific research over the years. First, there are many types of dementia, each with a different cause. The two most common are vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. While vascular dementia is caused by a multitude of tiny strokes in the brain and is usually associated with risk factors like high blood pressure and smoking, the cause of Alzheimer’s disease is much less well understood. The short version of what we do know is that a variety of genes and other factors appear to influence the accumulation of “senile plaques” (made of a naturally occurring protein called beta-amyloid) and “neurofibrillary tangles” (made of another naturally occurring protein called Tau) in the brain which, along with loss of brain cells, are the hallmark pathological features of the disease (for a more in-depth, if slightly dated, account of the many different biological processes that seem to contribute to Alzheimer’s disease, have a look at this excellent review article published in 2010 in the New England Journal of Medicine).

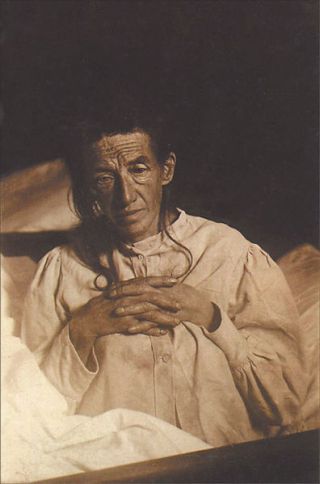

As an interesting side story, the fiction of Still Alice seems to have been based in part on the very first case of Alzheimer’s disease described by the eponymous German psychiatrist in 1907. Dr. Alzheimer’s first patient was a woman named Auguste Deter who, like the film character Alice Howland, developed severe memory problems at an unusually young age. Hospitalized when she was 51 years old, Deter died just 5 years later. In the 1990s, Deter’s patient records and brain tissue – preserved in microscope slides through the years – were rediscovered and reanalyzed. This testing confirmed the original pathology of plaques and tangles in her brain that we recognize as stigmata of the illness today, while also more recently revealing the presence of a mutation in a gene called presenilin 1 that, among other things, regulates the production of beta-amyloid.1 This gene is associated with an early-onset form of Alzheimer’s disease that runs in families and was the same gene that accounted for Still Alice’s Howland becoming symptomatic at such an early age.

While early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (occurring before the age of 65) is rare, the usual late-onset Alzheimer’s disease is quite common, affecting up to 35 million people worldwide.2 It becomes increasingly common as we age, such that past the age of 85, as many as 1 out of 3 people will have the disease.3 The risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease can be estimated by testing for other genetic abnormalities such as within the gene apolipoprotein E (apoE) or by positron emission tomography (PET) scanning of the brain for beta-amyloid accumulation. But despite these advances and their potential for early diagnosis and possible prevention before the onset of symptoms, the predictive value of these tests remains an inexact science. Aside from some of the inherited forms such as those related to presenilin mutations, genetic tests and brain scans do not guarantee that one will, or will not, develop Alzheimer’s disease. And so, the longer we live, the more likely we are to develop Alzheimer’s disease, but for most of us, there’s no way to tell for sure.

As if those facts aren’t sobering enough, consider that while our extensive knowledge of the biochemical abnormalities within the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease has led to the development of very sophisticated treatment strategies for investigation, none of these treatments has yet been shown to be effective. News headlines from earlier this year touted encouraging preliminary results from research with a new medication that reduces beta-amyloid accumulation, but taken together with disappointing results from many other very similar drugs to date, there is good reason for skepticism. In fact, reading the finer print, the early results of the new medication only suggest that cognitive decline may be slowed, not stopped. To date, no FDA approved medications (which aim to boost levels of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine) and no investigative treatments for Alzheimer’s disease (targeting beta-amyloid) have been associated with actual cognitive improvements and in some cases, the experimental drugs have made symptoms worse.

Another recent headline promised that a “new Alzheimer’s treatment fully restores memory function,” but this was based on an animal study in which ultrasound was used to remove beta-amyloid from the brains of mice. Unfortunately, despite the great value of animal research, encouraging therapeutic results in animal models often do not translate to positive results in clinical trials involving human beings. So, it remains to be seen, following years of necessary research ahead, whether such strategies might be effective in people. Furthermore, with regard to beta-amyloid, some researchers are beginning to question the importance of its accumulation in explaining Alzheimer’s disease altogether. Beta-amyloid accumulation occurs in those without dementia and in Alzheimer’s disease, the amount of beta-amyloid in the brain is not well correlated with disease severity.2 And for all the emphasis on plaques and tangles, Alzheimer’s disease is also associated with the widespread loss of brain cells that is the best correlate of cognitive impairment. Apart from the potential to prevent this from happening in the first place, actually reversing this process through neuronal regeneration is well beyond the scope of current therapeutic technologies.

If all this pessimism sounds too curmudgeonly, you’re right, it is. The truth is that due to years of rigorous scientific research, we have learned an amazing amount about Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, the amount that we now know is comparatively huge and therefore unusual for a psychiatric illness, so much so that many no longer think of it as a psychiatric disorder at all (which some might define, with tongue in cheek, as a disorder without a known cause), but a neurologic disease. And with all that we do know about it, the potential for the development of effective treatments holds great promise. It’s just that while there is good reason to be optimistic for the future, none of that promise has yet to be realized.

A friend’s mother recently died at the ripe old age of 97, having lived an active life up until a hip fracture, several strokes, and the subsequent development of dementia landed her in a nursing home for her final years. When she finally passed on, my friend was sad, but he remarked how in a way, he had already mourned her loss a year before when her dementia advanced and the person he knew faded away.

If there are saving graces in dementia, one is that as our sense of self fades, the kind of existential suffering that is linked to self-awareness often fades along with it. And while that is still sad in its own way, let’s think about this philosophically for a moment. Is it tragic that infants are unable to speak, cannot control their bladders and bowels, require total care from parents, and lack the kind of selfhood that we enjoy as adults? It’s not, because this is how life begins, with great potential lying ahead.

On the other end of life, dementia renders us infant-like with only death lying in wait, but behind us, we have hopefully led full lives, with all of our experiences and accomplishments fixed in time. It’s this perspective that we as caregivers – whether volunteers, recreational therapists, nurses, doctors, family members, and children – must embrace in our search for grace amidst tragedy. This other kind of grace, expressed through sacrifice and compassionate care, is captured in the quiet nobility of Still Alice’s Hollywood ending and at least for the moment, is the best we have to offer those with dementia. And that is something.

References

1. Muller U, Winter P, Graeber M. A presenilin 1 mutation in the first case of Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurology 2013; 12:129-130.

2. Sorrentino P, Iuliano A, Polverio A et al. The dark sides of amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. FEBS Letters 2014; 588:641-652.

3. Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. NEJM 2010; 362:329-344.

Dr. Joe Pierre and Psych Unseen can be followed on Twitter at https://twitter.com/psychunseen. To check out some of my fiction, click here to read the short story "Thermidor," published in Westwind earlier this year.