Dementia

Navigating the Complexities of Cognition and Brain Aging

How proactive habits can empower you to shape your brain's resilience.

Posted February 16, 2024 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Changing your behaviour now reduces your future risk of dementia dramatically.

- The 20th-century saw a remarkable leap in human longevity.

- Our memory isn't like a single muscle weakening with age; it shows many complex changes.

- Differing cognitive processes are affected in different ways by brain aging.

Our aging world

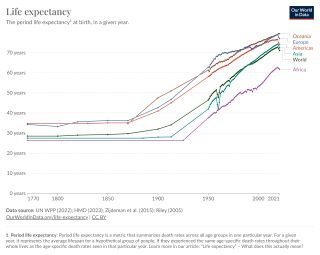

The 20th century saw a remarkable leap in human longevity. People born in 1950 could expect to live 20 years longer than their grandparents. Imagine a world where the older population (over 60) outnumbers children (under 14) for the first time ever. This major demographic shift has profound implications for society.

The aging brain

As we age, changes in mental abilities are a natural outcome, influenced by various factors affecting the brain. The flexibility of brain tissue diminishes, influencing its ability to rewire efficiently, and thereby affecting learning and memory. Communication speed between nerve cells slows down, contributing to reduced reaction times and processing speed. Natural loss of neurons (nerve cells) occurs in specific areas, influencing cognitive functions. While some of these changes are inevitable, adopting a healthy lifestyle with physical activity, mental stimulation, social engagement, and a balanced diet can significantly support brain health and cognitive function as we age.

While some abilities, like remembering specific events (episodic memory), tend to decline with age, others remain stable or even improve. Our understanding of the world and vocabulary (crystallized intelligence) often stay steady or even increase with experience. Additionally, some abilities like focusing on specific tasks (selective attention) and remembering unconscious habits (implicit memory) show minimal decline even as we age.

Some people maintain sharp mental acuity well into their later years (so-called super-agers), contrasting with others who experience a more pronounced decline.

What is metacognition?

I want to start with how we each think about and manage our own thinking and self-awareness. This is known as metacognition, and it is an essential cognitive skill involving the capacity to observe, regulate, and manage our cognitive processes—the one cognitive skill that rules them all. Metacognition plays a central role in our everyday functioning.

Is metacognition affected by normal aging? No, probably not, possibly not, or if it is, not in ways that are in lockstep with age-related changes in memory:

‘… in contrast to well-documented episodic memory deficits that occur with advancing age (for a review, see Hess, 2005; Zacks and Hasher, 2006), metacognitive processes associated with memory may experience little to no age-related decline in some circumstances (Castel, Middlebrooks, & McGillivray, 2016; Hertzog & Dunlosky, 2011)’. (source)

Differing cognitive processes are affected in different ways by brain aging—some remain unaffected, some improve, and some decline.

Aging memory

Our memory isn't like a single muscle weakening with age; it's a complex system where different parts experience unique changes. Remembering long-held information like vocabulary (semantic memory) usually improves with age, reflecting years of learning. Remembering specific details of recent events (episodic memory) might face some decline, similar to recalling what you just read in a newspaper article. However, skills like playing an instrument (procedural memory) often remain stable, proving practice makes perfect.

Even memories from years past (very long-term memory) tend to stay strong, as faces and personal experiences remain readily accessible. Interestingly, short-term memory, responsible for holding onto things like phone numbers for a few minutes, shows minimal decline with age. While forgetting where you placed your keys (working memory) might become more common, it's often the source of the information (source monitoring), not the memory itself, that causes the slip-up.

Abnormal changes in memory

As we age, occasional forgetfulness is natural, like misplacing keys or forgetting names. Yet, persistent forgetfulness affecting daily life demands attention. Watch for signs like increased difficulty recalling familiar information, struggles with routine tasks, challenges learning new things, repetitive actions, and difficulties in decision-making and financial management. Vigilance is key for cognitive well-being.

While occasional memory lapses are commonplace, a distinctive shift occurs when forgetfulness extends beyond minor instances. Dementia isn't a single disease, but a constellation of symptoms stemming from various underlying causes.

“Another way memory loss happens is when people are struck by one of the several, terrible, varieties of dementia, where they can lose all sorts of memories: autobiographical information about themselves, biographical details about others, information about the world at large. Life for the person with dementia gradually empties of colour and detail. Gaps appear in their conversation, as they lose the thread of the tête-à-tête. Gradually, insidiously, their condition worsens, and they may begin to fail to recognise the people they know and love; their minds gradually seem to become blanker, with no thoughts coming to mind, or if thoughts are articulated, they are usually thoughts about the immediate here and now—the person becomes ever more trapped in a continual present, unable to make the mental journeys along the timelines to an imagined future or an experienced past.” (source link)

Dementia is an umbrella term

Dementia is an ‘umbrella’ term for a spectrum of symptoms indicative of cognitive impairment. This condition manifests through cognitive, behavioural, and psychological symptoms, all stemming from biological changes in the brain. Alzheimer's disease is the most prevalent cause (about 65 percent of cases).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Ed, revised (DSM-IVr), outlines stringent criteria for diagnosing dementia. Central to these criteria is memory impairment, encompassing a diminished capacity to learn new information or recall previously acquired knowledge. Additionally, the presence of one or more accompanying factors is considered, such as aphasia (language disturbance), apraxia (impaired motor activity execution despite intact motor function), agnosia (failure to recognize or identify objects despite intact sensory function), and disturbance in executive functioning, reflecting impaired planning, organisation, sequencing, and abstraction abilities.

Crucially, these cognitive deficits must result in functional impairment within social or occupational domains.

Presidents and dementia

If you’re a fence-sitter or a political partisan, remember that cognitive functions are decomposable, slips of memory are common in aging (unless you’re a super-ager), and for a clinical conclusion regarding dementia you must show that cognitive deficits result in functional impairment within social or occupational domains and that these deficits represent a significant change from previous levels of functioning, quite a big ask to provide evidence for.

The message of hope regarding dementia

Changing your behaviour now reduces your future risk of dementia dramatically.

The modifiable risk factors for dementia are lower levels of education, hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, low social contact (loneliness) excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, and air pollution.

Cumulatively, they add up to about 40 percent of cases, preventing this number of cases would be an astonishing achievement.

References

Aggleton, J. P., Vann, S. D., & O'Mara, S. M. (2023). Converging diencephalic and hippocampal supports for episodic memory. Neuropsychologia, 191, 108728.

Aggleton, J. P., & O’Mara, S. M. (2022). The anterior thalamic nuclei: core components of a tripartite episodic memory system. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 23(8), 505-516.