Relationships

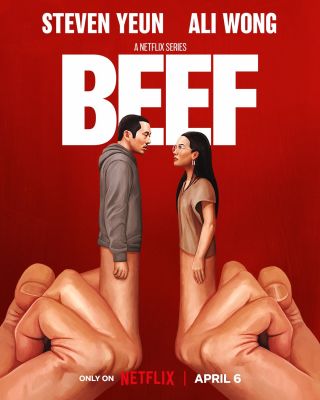

Netflix’s "Beef" Spotlights Squalor of Our Hidden Inner Life

Ali Wong, Steven Yeun, and a stellar cast demolish tropes in A24's new series.

Posted April 10, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

I had just finished watching Netflix’s "Beef" in three sittings, and I was scheduled to play tennis with a friend, but I just felt like crawling into a hole and hiding. I was destroyed. While the previous week, I played with verve, now I felt exhausted, heavy, in the “sunken place” as Jordan Peele put it in "Get Out." I was feeling some things.

Pace yourself when you watch this show. It packs a wallop. (Minor spoilers ahead.)

"Beef" is an existential dramedy, a dark dom-com as I put it, with incredible acting, writing, directing, cinematography, and sets throughout. I think it’s a breakthrough serial for Asian Americans in particular. "Beef" showcases immense Asian American talent in leads Ali Wong and Steven Yeun, as well as a deep supporting cast throughout, who raise a collective middle finger to stereotypes of Asian Americans as unemotive, expressionless model minorities, destined only to play silent, sidekick, worker-drone roles and never top the bill. This is one show that does emotional labor for us all.

"Beef" starts with an incident of road rage, then tumbles into a spy vs. spy back-and-forth, as Wong and Yeun's characters keep upping the ante against each other as exponential opponents and antagonists, before deepening into intergenerational trauma and the roots of their ills, and drilling into our emotional core. A24’s 10-episode limited-run series is a catastrophic, raw, and cautionary muse for our times, revealing narratives of unresolved emotion spiraling into pyrrhic, nihilistic deeds, leaving all parties, viewers included, exposed, spent, aching, and agonized for comfort.

As I said, pace yourself.

I’m often tagged as “calm and responsible,” yet I along with several Asian American friends have said that we found our angry selves mirrored in the show, going so far as to call it "a documentary." Confession: I’ve opened up my car window four times in the last 10 months to shout at the driver honking behind me, “Don't you see what's in front of me??!!” I had stopped for pedestrians or oncoming traffic, yet, here I was, the target of someone’s selfish, unreasonable impatience.

“Don’t you see what’s in front of me?”; “Don’t you see what’s behind me?”, “Don’t you see what’s on my plate?” are all metaphoric themes from our deepest interior, the unseen place that desperately wants to be seen, safe, understood, and perhaps even victorious.

"Beef" exposes wounds of the Asian American—and human—psyche that must be faced.

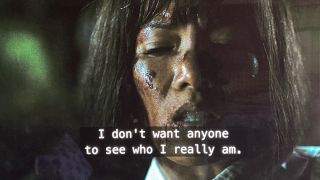

Shame

“If others knew my secrets, no one would love me.” There are many routes to shame, or feeling inadequate and unlovable, from imprints we get from our family of origin to the ways society and culture send us messages about our inadequacy and unacceptability. Wong as Amy Lau poignantly says, “I don’t want anyone to see who I really am.” She is overidentified with her most horrid narrative view of self, and unable to see her common humanity with compassion and generosity. Shame is a potent driver of suicide, and the movie opens with Danny buying implements to end his own life.

Suffering: There’s always a banana peel.

Some research shows Asian Americans are more pessimistic than white Americans, yet also as high in optimism. The First Noble Truth tells us “life entails suffering.” Histories of marginalization, subordination, colonialism, incarceration, exclusion, and so forth can lead to shame and a seemingly inescapable darkness. In Lee Isaac Chung’s "Minari" (also starring Steven Yeun, see my review in the references), catastrophe awaits behind every dawn. The so-called “American dream” is not ceaseless uplift, particularly for the marginalized and vulnerable.

Blame: There’s always a banana peel, and someone else dropped it.

We didn’t do this to ourselves. Someone did this to us. Someone else is to blame. We never got a fair shake. We were never loved unconditionally. As Audre Lorde said, “for to survive in the mouth of this dragon we call america, we have had to learn this first and most vital lesson—that we were never meant to survive.” All vulnerable people struggle between our own agency and autonomy, and what others have done and are doing to impair our possibilities.

A bereft emptiness is at our core.

Amy, Danny (Yeun), and George (Amy Lau’s husband played by Joseph Lee) all reveal a miasma of uncertainty and emptiness they’ve contended with all their lives. None of them received unconditional love from their parents, but criticism, narcissistic expectations, fear, and shame instead. They received what analyst Michael Balint called “the basic fault” or the lack of love in early life relationships, which has become echoed in what I call “the great chasm” of society, all the ways that society does not provide attuned understanding, safety, empathy, and love to all, and how many of us get caught up in the contingent self-esteem of wealth, status, achievements, and looks, instead of an inherent self-worth based on our humanity itself.

As Asian Americans, I think we were always wearing masks, especially to outsiders, but even to each other, and to ourselves. A pandemic happens, racial injustice surfaces more prominently—and history erupts. “I don’t want anyone to see who I really am.” But who are we? At the core? "Beef" reveals an answer in its closing scene, with Amy collapsed on a now-hospitalized-and-on-life-support Danny.

The grim—and tender—underbelly of the inner life is that we need each other. Asian Americans need specific attention from each other. And we have let each other down. We shouldn’t need to be reduced to the rawness of open wounds to realize this, but it’s exactly what has happened during the last few years.

"Beef" lands as the call of the century: a call to do better, to open our eyes and hearts to the needs and hurts we all carry, on this difficult Earth where we are so close to each other, and yet ache at all the space.

© 2023 Ravi Chandra, M.D., D.F.A.P.A.

References

Chandra R. Eight Questions for Understanding and Healing Resentment. Psychology Today blog, August 26, 2022

Chandra R. Which of Six Power Types Will You Embody and Support? Psychology Today blog, September 15, 2022.

Chandra R. MOSF 16.4: Film as Metaphor, Myth, Virtual Reality and Stepping Stone from Dismemberment to Belonging (with a review of Minari). East Wind eZine, August 21, 2021.

Chandra R. Memoirs of a Superfan Vol. 15.2: Lama Rod Owens and the Emotional Body of Asian Americans. East Wind eZine, August 24, 2020