She Knows Why You’re Into That

Whether you’re turned on by latex or leather, monsters or masochism, sex educator Tina Horn wants to help you understand why.

By Devon Frye published May 7, 2024 - last reviewed on May 11, 2024

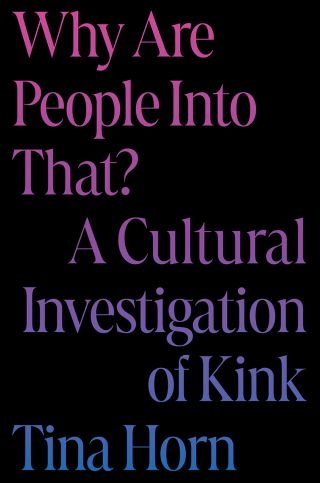

Tina Horn has always been into sex—having it, talking about it, analyzing it, deconstructing it, celebrating it. Her fascination with the myriad ways sexuality manifests has taken her from dominatrix dungeons to indie porn sets to sex-ed workshops, where she helps people make sense of—and find joy in—their most unique predilections. In her new book, Why Are People Into That?, based on her podcast of the same name, Horn explores how even the most niche fetishes, from cake-sitting to cannibalism, have roots in universal human desires—and how talking more openly about what turns us on could change all of our lives for the better.

What first appealed to you about being a dominatrix?

When I was in my early 20s and desperately needed a job, I learned about the existence of professional dominatrixes from books. Every time I read about this world, in fiction or nonfiction, my attitude was, I could do that! To a young woman with a modern literature degree, it seemed like the best paid improv gig in town—part field research, part theater.

What did your time as a dominatrix teach you about sexuality?

That it manifests differently in every individual who has ever lived or will ever live. And that just because I knew what a foot fetish was didn’t mean that everyone who walked in my door had the same kind of foot fetish; each one intersected with different aesthetics or forms of power play to create an entirely new fantasy. But there were patterns to study—a desire for vulnerability, the thrill of transgressing a taboo—which helped me learn to anticipate what each client wanted or didn’t even know to ask for. That’s still very present in what I do today.

Some people are uncomfortable to learn that you work in sex. What other reactions are common?

It’s like that classic joke: If you tell someone you’re a doctor, they pull down their pants and say, “Have a look at this rash.” A lot of people start oversharing—I’m often treated like a sex therapist, except I don’t get paid. The misconception is that, because I have transgressed the boundaries of what people consider taboo, they assume I have no boundaries—therefore, they give themselves permission to have no boundaries. Yet what they don’t realize is that it actually takes a great deal of energy to design and maintain the boundaries that allow me to transgress those taboos. Still, if you really need to talk to me about your sex life, I have a rate for that—and sometimes that rate is just a pint of beer.

Your work has exposed you to dozens of kinks. Were any particularly hard for you to understand?

I’m usually inclined to be curious about sex acts even if they don’t turn me on. But there are still certain kinks that I just can’t shake my discomfort around. One is sploshing—essentially wet and messy play, often with food but sometimes with other substances, like mud. For the book, I really pushed myself to understand sploshing—both what people like about it and why I dislike it so much.

What did you learn?

A woman named Darla DeVour, who has devoted her creative life to sploshing, told me, reverently, that sploshing is almost the eroticization of death. That may not be the first thing you think of when you see people slinging mud or cream pies at each other! But it’s ultimately about dissolving the self—and that was something I could understand. That’s what this project is all about: understanding desire by breaking it down into archetypes—not to be reductive, but to universalize it in the name of curiosity and compassion.

The DSM no longer labels fetishes as mental disorders in themselves. That’s progress, but is it enough?

It’s good that a lot of paraphilias, along with different gender identities and sexualities, are no longer treated as disorders—except if they cause “distress.” But distress can come from not having community support, or from seeing “foot guys” mocked on Sex and the City; women who get off on masochism might be shamed for being “bad feminists.” There are all kinds of reasons for our desires to cause us distress, but we’re not having enough honest conversation to understand the differences. Luckily, there’s a growing movement in psychology to rectify that—but there’s still a lot of weeding that needs to happen to really change the ecosystem.

What can people—even those who don’t identify as “kinky”—gain from learning about kink?

In kink, we have a saying: Don’t yuck anyone’s yum. But we can still have the humility to admit that there are some things we have a persistent yuck about. What if we simply try to better understand our yucks? My goal wasn’t to turn myself into a born-again splosher; the goal was just the inquiry itself. My hope is that more people will apply that curiosity to what new lovers, old lovers, friends, or public figures like. We might even solve some of the horrible problems caused by sexual repression if, instead of scorn and shame, we showed up with compassion.