The Art and Science of Great Conversations

Why you should speak up, and 6 ways it can go wrong.

By Psychology Today Contributors published May 2, 2023 - last reviewed on May 19, 2023

Conversation is a lot like art. It is one of those uniquely human experiences that distills so much complexity and exhibits such infinite variety that it verges on the indefinable. Unlike art, however, conversation is not a virtuoso endeavor. It is not only inherently an ensemble enterprise, it’s also how we share what we know, date and mate, and find security. Conversation has extraordinary powers to excite, our neurons being so sensitive to face-to-face engagement that they rapidly activate reward systems in our brains. Yet surveys show that it’s losing ground to texting and other asynchronous forms of communication that, at best, provide some pale illusion of satisfaction.

I. The Hidden Heart of Every Conversation

Dialogue is the most basic social covenant—an agreement to cooperate—and the most sophisticated.

By Valerie Fridland, Ph.D.

Rarely is anyone ever taught how to converse. Yet we all seem to know how to make conversations proceed. Even when we aren’t brilliant raconteurs, we all follow certain hidden rules for managing our tetes-a-tetes. We take turns. We strive to be clear. We speak in snippets, not

soliloquies.

What factors drive our conversations forward?

Unspoken Agreements

Conversation rests on, first and foremost, an agreement to cooperate. People implicitly consent to work together to be mutually understood. The idea that successful communication requires us to follow and, crucially, recognize certain culturally absorbed conventions was first articulated by British philosopher of language Paul Grice in the 1970s.

In observing the so-called cooperative principles, we seem to follow some basic ground rules, which Grice termed “conversational maxims” that help us figure out what to infer from what people say and how they say it.

The maxim of relevance ensures that what we say relates in some way to what has been said before. The maxim of quantity urges us to say enough to be informative, but not too much.

The maxim of quality binds us to be truthful, and it explains why we normally believe what others say, even if they are strangers. Finally, the maxim of manner has more to do with how we should say things—directly and clearly, unless there is a good reason not to.

Even when we flout the rules, other people will work to figure out how the apparent violation still supports the conventions. For example, if you ask me out on a date and I say I have to wash my hair, you interpret my response as relevant to what you asked and deduce a softened no.

Such intentional rule-breaking is also what helps us understand unstated meaning when people appear to be underinformative (breaking the maxim of quantity). For instance, if you ask me whether I like Bob and Carol from the office, and I reply, “I like Carol,” my very lack of informativeness in response reveals the real answer (that I like Carol but not Bob). Such strategic flouting of the rules allows us to be polite and indirect.

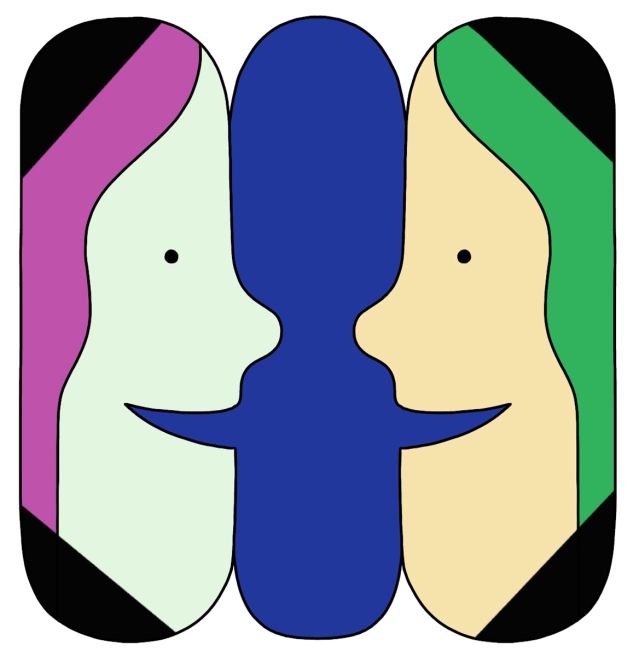

When Interlocutors Align

We not only follow unspoken rules, we also adjust our speech behavior to our conversation partner to facilitate communication and social approval—what’s known as communication accommodation (or alignment) theory (CAT). The direction and extent of adjustments go a long way in determining whether we come out of a conversation feeling that it was successful.

According to CAT, a speaker’s personality, status, and social background influence whether and how much someone will adjust their speech to match those they are talking with. Those with more interest in social approval and who have higher levels of agreeableness and self-consciousness generally modify their conversation more than those who do not score high on such scales. Those of high status accommodate less, as do people of dissimilar backgrounds.

The more positively speakers view an interaction and/or conversation partner, the more they tend to accommodate each other’s linguistic style. And, similarly, divergence—the opposite of accommodation—occurs at points when speakers want to increase social distance, as during heated discussions or conflict.

In conversation, CAT plays out as participants pick up one another’s vocabulary when discussing something—mimicking a word choice that their conversation partner used—rather than introducing a different term. (Replying, for example, “That’s a nice ride!” to a friend who says, “Check out my new ride.”) This also explains why we might shift styles when talking across generations or in power-based contexts, as in not talking about our “new ride” with grandpa or our boss, but instead using a more neutral term such as “car.”

Speakers also unconsciously adjust loudness, pitch, syntax, and speech rate to match those they talk to, and they can even converge on phonetic characteristics—for instance, unconsciously shifting toward slightly more Southern vowel pronunciations (like baa for bye) if their conversation partner has a Southern accent. Because the speaker who has more power or social status will be the one to whom the accommodation is directed, such accommodation might explain why and how new speech features spread over time within communities.

Why make any accommodations at all? Increased speaker alignment leads to more favorable social outcomes, in particular a more positive impression of those involved in the conversation. For example, in a 2016 study that manipulated whether a speaker came to a conversation with higher or lower status, researchers found that when less powerful participants in an interaction made adjustments to a higher status speaker, they were viewed more positively, as was the degree of conversational rapport. When among strangers or equals, accommodation helps manage social distance and increase perceptions of conversational quality.

In the nuanced marvel that is conversation, drawing deeply on social and cultural understanding, accommodation stops short of mimicking. Both over- and under-accommodation can lead to the feeling that others are disingenuous, overly familiar, uninterested, or unpleasant.

For example, if a speaker continues to use only -ing endings (walking) when others have shifted toward using more informal -in’ endings (walkin’), this might lead to a perception of stiffness or pretension on the part of the under-accommodating participant. In contrast, think of how parents might try to adopt a youthful speech style, using slang and overly colloquial speech to relate to their teenagers. Throwing in a like or dude here or there might make a teen feel affirmed, while sticking them in every sentence would come across as mocking. Instead, genuine accommodation is fairly unconscious and natural or risks coming across as sucking up or patronizing.

In short, there is much going on behind the scenes to make our conversations successful. We usually all want the same thing—to leave a conversation feeling positive.

II. Why You Really Should Speak Up More

We love ’em when we have ’em, but fear of being boring—and other misperceptions—leads people to quit conversations prematurely or avoid them altogether.

By Mark Travers, Ph.D.

Rewarding as conversations can be, they are unknowable in advance. That unpredictability contains enormous possibility, but it also can give rise to anxiety, providing opportunity for misconceptions about conversation to flourish. Often enough, this creates a barrier to building relationships, preventing people from really connecting or understanding each other.

For starters, people sometimes hesitate to even initiate conversations because they mistakenly fear that they might run out of things to say. Or they pull the plug on a good discussion, thinking, wrongly, that those that last for more than a few minutes are perceived as boring by their conversation companion.

“Having a good chat is one of daily life’s most rewarding experiences, and yet people are often hesitant to set aside significant amounts of time for conversation because they are concerned that they will run out of things to talk about and that their conversation will grow dull or awkward,” says Michael Kardas of Northwestern University.

He and his team recruited pairs of strangers to engage in conversations with each other in an experimental setting. The researchers paused the participants every few minutes and asked them how they felt the interactions were going.

After the first few minutes of conversation, people tended to indicate that they were enjoying themselves—but also that they feared they would run out of subjects to talk about as the discussion continued and that things would go downhill. Yet, in fact, there was no drop-off in interest or enjoyability as the conversations continued.

The longer they lasted, the more lively and pleasurable the exchanges became. “As the conversations continued, people found more material to talk about than they had expected to find, and they enjoyed themselves more than they anticipated,” Kardas reported in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. “In general, once people begin talking, they tend to find things that they share in common, and these commonalities propel the conversation for quite some time.”

You Also Learn More Than You Realize

In addition to misunderstanding the hedonic trajectory of face-to-face talk, people underestimate the amount of information they get out of conversations, even with random strangers encountered in daily life. They not only misjudge how much they will learn, but also how much pleasure they will get out of the social interaction, finds a team of researchers led by Nicholas Epley of the University of Chicago.

The undervaluing of learning seems to stem from the inherent uncertainty of conversations. It’s difficult to anticipate what one could discover before actually speaking with someone.

Epley’s earlier work has shown that people consistently underestimate the interest of others in connecting through conversation as well as how much they themselves—whether introverts or extroverts—will enjoy it. One upshot is that commuters travel in silence rather than engage with a seatmate. They not only miss out on a positive experience each time, they also fail to learn the value of social engagement in general.

Contributing to the missed opportunities is a reticence bias. People mistakenly believe that they will be liked more if they speak less, but studies show that to be thought interesting, they need to speak more than half the time in a conversation. Researchers at Harvard and the University of Virginia found that those who speak more are viewed as more endearing than those who speak less.

Further, it didn’t matter whether the conversational goal was to be liked, to be thought interesting, or to enjoy themselves. Reactions to all three aims were highly correlated; conversation partners formed global impressions of each other.

The reticence bias can prompt people to pass up worthwhile chances to socialize. Or they may unintentionally come across as uninterested or unengaged by wrongly believing that they need to pull back on their contributions to a conversation.

The shared advice of the researchers? If you want to forge deep and meaningful relationships with others, keep talking face to face. At the very least, you’ll be happier.

III. How to Have a Great Conversation

The sense of connection that makes talk so exhilarating comes from an array of synchronization strategies we unconsciously deploy.

By Frank T. McAndrew, Ph.D.

One of the most remarkable and least appreciated things about human social life is the speed and fluidity with which talk bounces back-and-forth between speakers, and there are few things more delightful than an effortless conversation. When conversational styles mesh smoothly, we walk away from social encounters feeling good, feeling connected, and flinging around words like rapport and chemistry to describe the experience.

That sense of interpersonal attunement is one of the biggest rewards for engaging in live, in-person interaction. And for many, it is one of the most welcome pleasures of postpandemic life.

Great conversations don’t just happen. We take measures to subtly synchronize with the conversational styles of others, sending little signals to seamlessly switch back and forth. And we generally launch the intricate dynamics of human communication with small talk.

Small Talk Gets a Bad Rap

How do great conversations start in the first place? The Oxford English Dictionary defines small talk as “polite conversation about unimportant or uncontroversial matters.” People claim to hate it—some because they perceive it as a waste of time and an impediment to meaningful conversation and others simply because they are not good at it. But small talk turns out to be a much underrated pillar of everyday life.

Studies indicate that people are happier when they talk to others, even if it is just strangers on a subway and even if it is just small talk. But small talk does much more.

It begets big talk. Many critiques of small talk are artificially framed as a contest between the benefits of small talk versus the benefits of deeper conversation, as if people must be forced to engage in only one or the other. Of course, you are bound to be disappointed if all of your conversations are nothing more than superficial loops of chatter about things that no one really cares about.

The trick is to be skilled in both types of talk. Rather than being antagonistic to each other, different levels of talk work in tandem to create effective relationships. Small talk is best used as a social lubricant, opening the way to more consequential topics.

Think of it as foreplay, synchronizing the level of intimacy between partners in a conversation and as a mechanism for signaling friendly intentions while simultaneously minimizing uncomfortable silences. The actual topics of small talk do not matter very much; its purpose is not to convey information but rather to serve as an opening act to warm up the audience for the meaty stuff to follow, the stuff that elevates, exhilarates, and expands us.

Attention Conveys Intention

We spend more time looking at our partner while listening than while speaking. It’s not just a way of signaling attention; it allows us to give feedback to the speaker—say, widening our eyes to signal surprise, interest, and agreement, encouraging the person to continue the interaction.

Attention has its own magic. We crave recognition from others, and there is experimental evidence that being ostracized or ignored by others creates a pain that is every bit as real and intense as that caused by physical injury. In our prehistoric tribal groups, ostracism from the group could essentially be a death sentence.

According to social attention holding potential theory (SAHP), developed by British psychologist Paul Gilbert, we compete with each other to have people pay attention to us. When other people take notice, we feel good, enjoying all kinds of positive feelings—confidence, belonging, acceptance. Knowing that you are being heard by your conversation partner is part of the larger phenomenon. (On the flip side, being ignored by others produces much darker emotions, especially envy, anger, and despair.)

Your Turn to Talk

At some point, however, we might tire of listening, and we display signs that we are becoming impatient. We may start fidgeting, primping our hair, or tugging at our clothing.

Escalating, we may start nodding rapidly as if to say, “OK, OK, OK,” and may even grunt or make fake sounds of agreement to get the speaker to shut up. Eventually, we may become more direct, making exaggerated inhalations and raising an index finger or even a hand as if we were a student in school trying to get a teacher’s attention.

A speaker not yet ready to yield the floor will avert their gaze and pretend not to see their partner’s nonverbal pleas. They’ll likely turn up the volume of their voice. A skillful speaker may even make eye contact with the listener and make a “stop” gesture with one hand, simultaneously acknowledging the request to speak and signaling an intention to honor it soon.

When the speaker is finally ready to turn the conversation over, they will decrease the loudness of their voice, gaze directly into the listener’s eyes, and slow the tempo of their speech so that the last syllable of the last word stretches out a bit longer than it normally would. A clear pause then serves as an invitation for the listener to jump in.

In most conversations, the exchange of roles from speaker to listener and back is seamless, and it is surprising how little talking over each other occurs. But then there comes that most awkward of signals to send—that you have nothing more to say and do not wish to speak.

If your partner appears to be turning the conversation over to you, but you are not interested in speaking, it is okay to just come right out and say so. Also, staying relaxed, maintaining silence, and avoiding eye contact will signal that you are comfortable allowing the other person to continue speaking.

Six Conversation Habits to Break

By Dave Smallen, Ph.D.

Interrupting

This can make it seem as if you don’t care what the other person has to say.

Story-Topping

This can shift the conversation from connection to competition.

Bright-Siding

Always encouraging others to be positive can feel invalidating.

Being Right

The conversation becomes about winning an argument.

Being All-Knowing

Explaining information without being asked for your expertise.

Advice-Giving

Sometimes people just want empathy.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of this issue.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Rawpixel.com/Shutterstock