Hallucination

Dory Previn's Voices

New documentary shows how Dory Previn anticipated the Hearing Voices movement.

Updated March 24, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- The film Dory Previn: On My Way to Where Tells the story of the singer-songwriter's experience hearing voices.

- Musiican Dory Previn intuited the principles of today's Hearing Voices Movement.

- Previn is remarkably articulate about living--and making peace--with auditory hallucinations.

Musician Dory Previn's career started in the movies. She and husband André Previn collaborated on dozens of songs for films, including "Theme from Valley of the Dolls," A new documentary, Dory Previn: On My Way to Where (directed by Dianna Dilworth and Julia Greenberg), premiered at this week's South by Southwest festival.

In the film, Previn explains that she wrote the enigmatic lyrics, famously sung by Dionnne Warwick, based on her own experience with prescription drugs, mimicking the circular thinking and unfinished thoughts that shaped her inner and outer dialogues when she was under their influence: "Gotta get off, gonna get / Have to get off from this ride / Gotta get hold, gonna get / Need to get hold of my pride."

Dory Previn: On My Way to Where spends less time on Previn's career as a renowned composer for film than on Previn's remarkable post-divorce solo career in the 1970s, when she released seven albums and published two autobiographies, Midnight Baby (1977) and Bog-Trotter (1980). As she suggests throughout the documentary, Previn's experience with hearing voices was fundamental to the music she wrote. The voices, she contends, were often collaborators. Her documentarians use archival footage, her books, journals, and music to let Previn speak for herself. And she has plenty of wisdom to share.

Previn was ahead of her time. Like many of her feminist contemporaries, she believed the personal was political. But her music was more revealing and intimate than any of her musical contemporaries--including frank expression of her relationship with her voices.

Previn, once tormented by her voices, established a healthy relationship--and artistic collaboration--with them. The documentary brings to light her copious journals exploring the evolution of her relation to them. Remarkably, her account of this evolution intuited what would become core principles of today's Hearing Voices movement. In Bog-Trotter she writes,

I began to question. What if those voices gave me no peace, not because they were sick, but because they were healthy? If it were true, that would mean all those guards, techs, nurses, doctors – all those learned experts with their degrees – all of them were wrong.

The Hearing Voice Network (HVN), founded in the Netherlands in 1988, is most active there and in the United Kingdom. The organization is at the center of today's Hearing Voices movement. A grassroots advocacy and activist group, HVN is a forum for exploring questions Previn was asking decades before such a movement was conceivable: What if hearing voices can be healthy? What if the experts—who would generally deliver a schizophrenia diagnosis to those who heard them—were wrong? In fact, in her journals, autobiographies, and music, Previn articulated what would become HVN's core tenets:

- Raise awareness of the diversity of voices, visions and similar experiences

- Challenge negative stereotypes, stigma and discrimination

- Help create more spaces for people of all ages and backgrounds to talk freely about voice-hearing, visions and similar sensory experiences

- Raise awareness of a range of different ways to manage distressing, confusing or difficult voices

- Encourage a more positive response to voice-hearing and related experiences in healthcare settings and wider society.

HVN publishes video testimonies by people who hear voices and establish a working relation to them. Rai Waddingham's testimony in "Getting To Know Your Voices," is an eloquent representation of a common narrative--from torment to collaboration--many in the movement describe.

Previn's "Mr. Whisper" is her most explicit musical expression of her relation to her voices: "When I am going / 'Round the bend / I got a wild / Imaginary friend / When I am driven / Up the wall / My old friend

He comes to call." The song is a plea for "Mr. Whisper" to stick around—and be helpful.

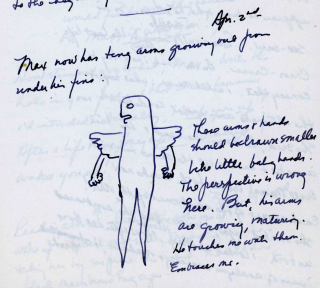

In her journals, Previn not only wrote about her voices, but drew semi-surreal portraits of them. She writes about this voice, whose name is Max, and others in Bog-Trotter:

"I politely invited the voices to come in quietly. A welcome was extended. They were free to exist in my head. The door was unlocked. I was willing to make them part of my reality as long as they behaved themselves. After a long period, I learned my first lesson, they had decided to accept my madness. A sensible dialogue would be possible only if I behaved sensibly toward them."

In 2013, Stanford anthropologist T.M. Luhrmann published an Op-Ed in the New York Times, urging mental health practitioners to consider a paradigm shift when it comes to diagnosing those who hear voices. She writes,

The Hearing Voices movement encourages people who hear distressing voices to identify them, to learn about them, and then to negotiate with them. It is an approach that flies in the face of much clinical practice in the United States, where psychiatrists tend to assume that treating such voices as meaningful encourages those who hear them to give them more authority and to follow their commands.

Lurhmann is is careful to point out that the variety of experiences of those who hear voices is vast, often a source of extreme suffering:

The more we know about the auditory hallucinations of schizophrenia, the more complex voice-hearing seems and the more heterogeneous the voice-hearing population becomes. Not everyone will benefit from the new approaches. Still, they offer hope for those struggling with a grim disease.

Dory Previn: On My Way to Where, presents illuminating footage of Previn discussing her voices onstage, and in public interviews on mainstream talk shows. In those interviews, as in her books, journals, and music, she questions whether her schizophrenia diagnosis is accurate. She wonders whether her experience should be classified as a disease at all.

As pyschology evolves to take patient testimony more seriously, practitioners would do well to take a second look at Dory Previn's work. On her own, Previn intuited the lessons of the Hearing Voices movement, establishing not only a therapeutic relationship to her voices, but a collaborative one. As she writes in Bog-Trotter,

Now I travel along a finely balanced line, with one head in fantasy and one head in reality. I won’t say which is which. No longer do I feel so alien in the 20th century. As long as I listen, and am watchful, and ever on guard, I am bound to be sure my inner friends love me. At last, we are integrated.