Memory

How Memory Can Help Us Cope With the Loss of Loved Ones

What Día de los Muertos can teach us about remembering and grief.

Posted October 29, 2021 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- How we grieve death depends on various factors, such as the nature of the relationship, circumstances, personality traits and more.

- Grief is a testament of human resilience and we can emerge and grow from it.

- Memorializing loved ones who have passed is a way of exploring meaning and authenticates our part in the mourning process.

- Memorializing allows us to galvanize relationships, sustain connections, and to recognize and honor those who have had a part in our lives.

As we approach holidays, sometimes feelings of grief and loss can arise in moments where we recognize that the loved ones we have lost are no longer with us to share the experience. Struggling with grief and loss, especially during holidays, can be tough.

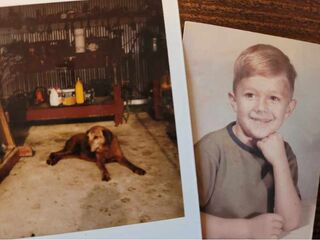

I remember as a child when our pet dog, “Lady” was too old and arthritic to go on. Lady was the love of our family. We bought her for twenty-five dollars. She had protected me once when another vicious dog tried to attack me. I put my arms over my head and crouched on the ground bracing for an attack that never came. It was Lady who jumped over me to stop the attack. I never forgot that amazing moment.

The love I felt for her is still a beautiful memory. But I also never forgot the pain of the day we lost her to disease and old age. As a child, it was hard for me to truly articulate my loss. Nothing could describe that pain.

Confronting loss is a part of our human existence

Growing up in my home allowed me to experience some rich diversity, as my mom, who was Mexican-American, introduced me to the cultural aspects of what it meant to be Mexican-American. My dad taught us about love for family, and my mom instilled a reverence for culture. I remember her bringing sweets back from the church one day and first hearing the words “Día de los Muertos" (Day of the Dead). Growing up in San Antonio, Día de los Muertos was a yearly festival filled with color, music, and food. The celebration would play an important role in my life moving forward.

Over the years, I have lost people. The hurt and pain can be tremendously impacting. Our attachments can be to an array of people or things in our lives. From a psychological perspective, research on bereavement shows us that the nature of a person’s attachments has implications for their grief reactions (Weir, 2020).

Stark reminders and the nostalgia of holidays

Holidays create nostalgia, and for many, holidays may also perpetuate nervous anxiety around feelings one has about what has been lost. Katherine Shear, an MD at Columbia University, has mentioned that the way we grieve a death depends on several factors, including circumstances surrounding our loss, unique personality traits we bring, the nature of our relationship, timing, context, and consequences associated with the loss (University of Louisville Depression Center, 2014). Dr. Shear also sees grief as a testament to human resilience, from which we can grow and evolve.

Memorializing our loved ones

Many years ago, as a younger artist, I participated in a contributive exhibit that brought local San Antonio artists together to share their work for a special art show around Dia De Los Muertos. It was here that I began to see things differently. This process of remembering through a celebration like Día de los Muertos gained more prominence in my processing of the experience of death.

Theorists like Moody and Sasser (2015) suggest that “memorializing allows individuals to explore life’s meaning.” While theorist Cann (2014) sees the process as a “way of allowing people to authenticate their part in the mourning process.” Other theorists like DeVries and Rutherford (2004), as well as Schwab (2004), see the potential of memorializing those we love as a way of "preserving our relationship with them."

The memories and experiences contained within us serve many functions. Memories help us understand our experiences and keep us connected. Memories can bind that connectivity in a positive way, moving us from avoidance to acceptance. The act of memorializing can provide a healthy conduit for channeling emotions. According to researchers Leming and Dickenson (2007), "memorializing" is a worldwide sociocultural practice whereby people preserve their relationship to a lost loved one through memories evinced in some form of practice or ritual.

Continuing our connections through memories

In a study on memorializing preferences, researchers from the University of Florida conducted a study based on a sample of 145 participants examining personal attitudes and life experiences with death. Their results reveal that although remembering can be painful, it can also bring comfort by connecting through a shared past (Bluck & Mroz, 2010).

In fact, according to research by Hagman (1995), remembering is a primary way for our relationships to be sustained once a loved one dies. Memorializing our loved ones during the holidays can galvanize our relationships and move us to creativity and commitment around the things in our own life. As stated by Bluck and Mroz (2017), “there is the impact we experience in the death of a loved one, but the distinction of remembering those passed is also a fundamental component of human life.”

Ways to memorialize our loved ones

Although Día de los Muertos is one way we can remember those who were a part of our life, there are other ways you can do this as well.

Public memorializing

Societal rituals are a way of publicly honoring loved ones while allowing us to share their story with others. This could be through a memorial website, a public donation, or support for things or programs that relate to a lost loved one’s former interests or talents. Other unscripted ways may be in the form of a family dinner in their honor or a social tradition like Día de los Muertos .

Personal memorializing

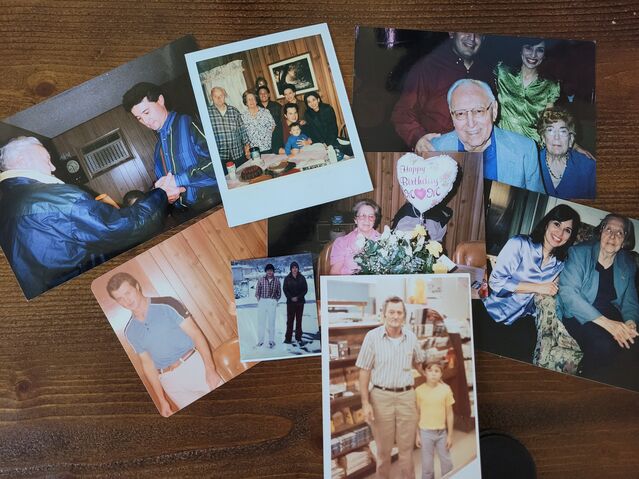

In this type of memorializing, a more personalized experience takes place for the bereaved (Bluck et al., 2019). Personally memorializing might include engaging with specific memories such as: incorporating a favorite recipe or meal from a loved one; listening to music they enjoyed; lighting a candle during Thanksgiving, Christmas, or other days; or creating a memory book and finding a special place in your home to enjoy pictures of them. According to researcher Moss (2004), such activities can spur the memory towards positive and realistic characteristics of a loved one while also affirming their significance in your life.

References

References

Bluck, S., Alea, N., & Demiray, B. (2010). You get what you need: The psychological functions of remembering. In J. H. Mace (Ed.), The act of remembering: Towards an understanding of how we recall the past (pp. 285–307). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bluck, Susan, & Mroz, Emily (2019). In memory: Predicting preferences for memorializing lost loved ones. Death Studies, 43(3), 154-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1440033

Bluck, S., & Mroz, E. L. (2017). The end: Death as part of the life story. The International Journal for Reminiscence and Life Review (in press).

Cann, C. K. (2014). Virtual afterlives: Grieving the dead in the twenty-first century. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. The Journal of American Culture, 39, 268–269. doi:10.1111/jacc.12566

De Vries, B., & Rutherford, J. (2004). Memorializing loved ones on the world wide web. Omega Journal of Death and Dying, 49, 5–26. doi:10.2190/dr46-ru57-uy6p-newm

Hagman, G. (1995). Mourning: A review and reconsideration. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 76, 909–925.

Moody, H., & Sasser, J. R. (2015). Does old age have meaning? In H. Moody & J. R. Sasser (Eds.), Aging: Concepts and controversies (pp. 27–51). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Moss, M. (2004). Grief on the web. Omega, 49, 77–81. doi:10.2190/cqtk-gf27-tn42-3cw3

Schwab, R. (2004). Acts of remembrance, cherished possessions, and living memorials. Generations, 28, 26–30.

Weir, Kristen (2020, June). Grieving life and loss. American Psychological Association, 51(4), https://www.apa.org/monitor/2020/06/covid-grieving-life

[University of Louisville Depression Center]. 2014, October 10, Katherine Shear, MD Presents a talk on the topic of Grief, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9qmZ9dYqQCs