Imagination

Obama’s 2nd Term: Expanding the Liberal Imagination

If liberalism is back can it be different this time?

Posted February 10, 2013

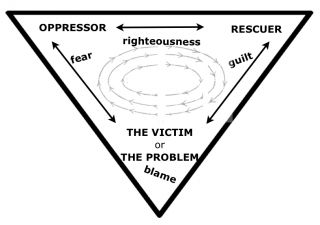

The predominant liberal, conservative and African American narratives keep African Americans at the bottom of the Drama Triangle.

I made a copy of President Obama’s Second Inaugural Address and broke it into six parts so that I could play any part of it for inspiration for the complex tasks that are ahead of us as a nation. I did not think it was a liberal speech. My contention has always been that Obama is Spiritually Liberal, but Socially Conservative in ways that I described two years ago. The stuff usually called social conservatism isn’t truly conservative.

Liberals, wishing for a call to arms, branded the speech a liberal speech. As Hendrik Hertzberg wrote in The New Yorker, “In front of the Capitol last Monday, Obama did not specify that creed. But the Tuesday papers did. OBAMA OFFERS LIBERAL VISION: ‘WE MUST ACT’ (the New York Times), A LIBERAL VISION (the Hartford Courant), FOR HIS SECOND TERM, A SWEEPING LIBERAL VISION (the Los Angeles Times).

I did not fall out of love with liberalism as so many did during the Reagan Revolution. To my mind, the advances in African American life would have been unthinkable without the power, earnestness, and dedication of liberals --from Abolitionists to present-day volunteers in organizations like the Innocence Project.

My view is that there would have been no Civil Rights revolution in the 1960s without liberals, some of whom were murdered as they pressed forward for justice for African Americans. The liberal-minded War on Poverty did make African American life better.

To repeat here what I wrote in a year ago in “Will the 60s Revolution Be Undone?”

“Resulting from it (the War on Poverty) were the Job Corps, Upward Bound, and the Food Stamp Act. President Johnson started massive federal funding for education with the Elementary and Secondary Education Act and made loans available to those seeking to go to college. The government assisted in the creation of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Millions were spent to form endowments for arts and humanities. Federal money went for cultural exchanges with other nations and cultural institutions in this country.

“The Social Security Act of 1965 authorized Medicare, thereby changing the lives of millions of older Americans. The following year welfare recipients of all ages received medical care through the Medicaid program.

“. . . The Cigarette Labeling Act of 1965, the Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act, the Child Safety Act, the Radiation Safety Act, the Flammable Fabrics Act, the Wholesome Meat and Wholesome Poultry Products Act, the Truth-in-Lending Act, and the Land Sales Disclosure Act.

“The modern save-the-environment movement started during our revolution with clean air and water quality acts and laws to protect animals and land. Liberal policies made a huge reduction in poverty rates during the 1960s. From 1959, the year before John F. Kennedy swept liberalism into power, until 1969, when Richard Nixon swept it out, poverty rates among whites fell from 18.1 to 9.5. Among blacks the rate fell from 55.1 to 32.

The American Racial Drama Triangle

I am happy that liberalism is back but I hope that this time it will find a new way to tap into the swirling emotions and shifting the roles—oppressor, rescuer, and victim— inside the American Racial Drama Triangle.

The predominant liberal, conservative and African Americans dramas keep African Americans at the bottom of the Drama Triangle.

The Drama Triangle shows the human conflict found in all dramatic stories; and it has a powerful hold on the racial narratives we tell ourselves in this country. With the Southern Strategy of the Republican Party, President Reagan was able to put together a winning electoral coalition by telling a very American story of African Americans as The Problem.

Great storyteller that he was, Reagan inserted into the narrative some vivid, inflammatory stereotypes like African American “Welfare Queens” driving Cadillacs and “strapping young bucks” using food stamps to buy T-bone steaks--all enabled by a liberal federal government. He was so successful that he convinced many Americans that "Government is not the solution to our problem government IS the problem."

All three roles in the Triangle need each other, and if someone plays one role, in time, he or she will play the others. Remember during the 2012 Presidential campaign, Mitt Romney, Paul Ryan, and many of their millionaire and billionaire friends saw themselves as victims. On and on inside the Triangle goes the swirling energy of blame, righteousness, guilt, and fear. This is how all dramatic stories are created.

President Obama was wise enough not to cast any of his voters as victims, as old-style liberals might have done. The campaign cast them as “rescuers.” I was in constant contact with grass roots black folk in Ohio and I can say with absolute certainty that they felt that it was up to them to rescue the nation and the world.

How Denial Becomes Transcendence

I know from experience that most African American individuals who escaped the bottom of the Triangle heard from their parents what I heard from mine: “Don’t you come in this house sniffling, telling me that someone did something to you. Nobody did anything to you.” In short “you are not a victim.”

We were encouraged to live “in denial” and I have not found a psychologist who has anything good to say about it. Denial is choosing to reject an empirically verifiable reality. Wikipedia adds: “It is an essentially irrational action that withholds validation of a historical experience . . .”

But there are some benefits to withholding validation of a historical experience. It could be an important step onto the road leading to transcendence of the effects of that experience. “Nobody did anything to you” might be a declaration that humans are connected to some place “on high” where what happened on earth doesn’t really exist.

In African American history the connection to this place was through the Negro Spiritual, which is the basis for what we call American music and is therefore America’s spiritual gift to the popular culture of the world.

For all that is wrong with the essentially irrational thinking that withholds validation of a historical experience, there are powerful assets that have never been dramatized and sufficiently made a part of the American story. When dramatized this body of untold stories could bring the richness of African (or primal) spirituality as a gift to a modern world, which needs it now.

I though of this gift often when viewing “Doctor Bello” a film by Nigerian director Tony Abulu, opening in 8 cities and 12 AMC theaters across America on February 22, 2013. It is a story about the universal, human connection between empirically verifiable reality and un-manifested aspects of reality, aspects which we are gaining more and more understanding of.

The logline for the film is: “The cure for cancer has been found. . .in the Sky Mountains of Africa.” The film takes us to a universal place of primal spirituality that Africans connected to before Christianity, Islam and American slavery came.

Filmed Stories are the Bibles of Our Lives

Most people cannot, by theoretical explanations, “get” a sense of the connection between the manifested and the un-manifested. For them the connections can only be understood through stories. “Doctor Bello” is a simple, beautiful story with a profound subliminal message.

In ancient times, stories in the Holy Books of Judaism, the Bible, the Koran, and the mythologies of all people conveyed as much as humans understood at the time about our connection to the un-manifested.

Throughout human history, in the best stories, there has always been a sense that characters in the natural world are connected to something unknown beyond themselves, something that can only have effect through the narratives that play in out individual or collective heads.

Our dimly perceived connection is put into stories by our imaginations, and we gain strength not primarily through understanding but through inspiration that strengthens faith. In the 20th century, due largely to the quantum revolution, we’ve gain so many new perspectives on how we, here in empirically verifiable reality, are connected to those aspects of the universe beyond time/space.

We need new stories that inspire and inform us. Science fiction writers attempt to tell us new truths. Films and television shows are filled with all kinds of supernatural dramas that illustrate and hope to reveal and inspire subliminal sense of our enhanced sense of what is “out there.” Hollywood is aware of our evolved understandings.

But rare are the stories in which the revelation of connection does not depend on animals, mythical creatures, plants, inanimate objects or forces of nature that are given human qualities (such as verbal communication) and used to illustrate the new understandings.

Many of the stories of African and African American life could supply some of these understandings, but decision-makers in the story industries –fiction publishers and film and television producers-- tend to limit African American stories they produce and distribute to either the slap-stick or to the “woe-is-us” traditions. The desire seems to be to limit African American stories to being metaphors for smaller, mundane truths rather than the larger transcendent ones that are in African American music, for example.

Too many times liberal Hollywood has been unwilling to create African American stories that dramatize what remains in African American communities of the kind of primal spirituality that Africans had before Christianity and Islam came, which enabled African American communities to rise above the degradation of slavery and its brutalizing aftermath, Jim Crow. That enabled entire communities to say “nobody did nothing to us.”

Post-Racialism and the Gift of Spirit

African American culture brings something much more profound than a metaphor for degradation. It brings the “Gift of Spirit,” W. E. B. Dubois called it in The Souls of Black Folk. Post-Racism provides a convenient reason to reject the gift. When the hunger for the gift gets so great that it cannot be rejected, it must be re-labeled as American rather than African American.

Better to re-label it than to violate the Iron Laws upon which illusions of racial superiority depends. This is what I was getting at in the post Obama is black but he’d better not say so.

The open and hidden laws of the American Racial Drama Triangle is that African Americans must remain at the bottom of the national narrative, even while in reality they rise to the top –some even to the White House. Those who rise are re-labeled as race-less, which means Villains and Saviors and Victims can remain in their assigned roles.

No matter how carefully my wording in posts that assert that slavery and its aftermath strengthened some sense of the connections between humans and the un-manifested world, I get a comment like: “It is racist for you to say that African Americans are more spiritually connected than other people.”

To me the comments, when they come from liberals, reflects that even after acknowledgement of all the vast riches that European Americans (Our Founding Fathers and millions of white people, for example) bring to our contemporary multiracial mix, there is a quick-trigger defensive anger (sometime fierce) when someone asserts that non-whites do not come to the American mainstream empty-handed.

There are some white liberals who need the feel of someone beneath them in the Triangle or else they experience a treat to their sense of purpose. It is a treat to their place as rescuers in the national drama. Rather recreating narratives in their minds in which African Americans bring value to our multiracial nation.

This is when the liberal mind often jumps to post-racialism and declare: “There is no such thing as race, anyway. I don’t know what you’re talking about. People are people. My real concern is global warming.” It is hard to construct a narrative in which you are being helped by someone that you’ve been rescuing as a victim.

While doing reporting for this post, among the 10 white friends I talked to the one with least resistant to the idea that African Americans bring spiritual gifts to American culture is a super patriotic, ex-Marine. He made no attempts to take the post-racial exit from the discussion. “Sure, every group brings something good and something bad to the mix.”

The two white friends who are most left-leaning were most angered and confused by the idea. My sample is not large enough for me to draw conclusions, but it did give me something to think about.

When comments came from white conservatives (and I got reactions from only two, on the Columbia University Linked-in Forum), both comments held that by even mention race I was a racist. There is a very effective way of escaping into post-racialism and pushing into irrelevance any attempt by any group to make any comparative statement about a non-white group’s worth. Referred to in code words African Americans are securely locked in their place as The Problem.

One of my posts expressed my view that by dramatizing a sense of revenge as the legacy of slavery, Quentin Tarantino “Django Unchained” made a deliberate attack on the power of spiritual transcendence that African American slaves strengthened for all human beings.

One of the comments to that post was: “To claim that the african american race carries the "spirit" of something that is missing from others is ignorance, and only lends itself to further segregative thinking.” I have no idea if this commenter was a liberal or conservative, but I can agree that if we are locked in the Triangle the claim will lead to “segregative” thinking.

Expanding the Liberal Imagination

The famous African American writer James Baldwin wrote: “It is only in his music, which Americans are able to admire because protective sentimentality limits their understanding of it, that the Negro in America has been able to tell his story.”

The story, as many liberals, conservatives and African Americans see it, is, in Baldwin’s words, a story of “statistic, slums, rapes, injustices, remote violence; it is to be confronted with an endless cataloguing of losses, gains, skirmishes; it is to feel virtuous, outraged, helpless,” and angry, I might add. Baldwin continued: “It is not a very pretty story: the story of a people is never very pretty.”

Despite Baldwin’s deep insight and liberalism’s centuries-old front line experience, the African American story can be “pretty.” In fact, it has to be. Images from the story that Baldwin speaks of are as destructive as crack-cocaine to the aspirations of many African Americans. Any community who remains cast as The Victim or The Problem cannot possibly experience success.

In his 1950 book The Liberal Imagination, Lionel Trilling wrote about the ineffectiveness of liberal total faith in rationality, progress, and the study of the empirically verifiable realities of economics and other public policy areas. Trilling suggested that only by adding insights into realms where only the imagination can enter will help us define who we really are.

If Trilling had known back then what we know now his claim might have been that only insights into realms where the transcendent imagination can enter will help us define who we are becoming.

George Davis is author of the new spiritual spy novel, The Melting Points, about three women pursued by danger as the clockwork universe melts around them. In development is a television series based on his soon-to-be-published nonfiction novel, Branches, which continues the spiritual journey that Alex Haley dramatized in “Roots.” It continues the journey of America towards becoming an exceptional, multiracial nation.