Stress

Just Sigh—It’s a Restorative Outbreath

A sigh is key to allowing the body to release stress and welcome relaxation.

Posted February 13, 2023 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Sighing is a form of outbreath that has multiple functions.

- The outbreath impacts the parasympathetic nervous system, helping one to “rest and digest” and override fight-and-flight responses.

- Combining sighing with expressive arts therapy expands the experience of the outbreath and body awareness.

We all sigh throughout each day. Most of the time it’s a reflexive action, something most of us rarely think about. Technically, sighing is just an expression of our outbreath and an exhale. When we breathe, two things happen. On inhalation, the diaphragm actually pulls itself down, flattening in order to allow us to breathe in. On exhalation, our respiration is much more passive and restful.

It is through controlling the outbreath (exhalation) that some remarkable things happen to our physiology. When we focus on the exhale, we can more deeply inhale, making the ability to sigh (a specific outbreath) a means to alter the body’s experience of stress. It’s a way to give emotions the capacity to shift, literally giving us breathing space to welcome restorative moments.

The simple experience of sighing has real possibilities for what I call “restorative embodiment”—focusing on the senses as a resource to support and reinforce self-soothing, invigorating, and recuperative experiences (Malchiodi, 2022). In my recent research with socioemotional learning with children and traumatic stress with adults, it is an effective place to help individuals identify the felt sense in the moment. It is also a way to “expel” what is distressful and make space for what is reparative, regulating, and restorative for body and mind.

The Purpose of Sighing

Sighing is a form of outbreath that has many different functions. The act of sighing can be a conscious or unconscious experience; it is often an autonomic response and reflexive action that is stimulated by stress, frustration, or boredom. A sigh is often used to non-verbally communicate emotions including anxiety or depression. In this sense, sighing can be a way to express a need for attention from others. When we sigh, we may be signaling others that we need support when stressed or that we need stimulation when bored or withdrawn. We also sigh to express contentment, joy, or relief—experiences of positive emotions that we may want to share with others.

Sighing is also a way to release tension in the body. This specific outbreath has a physiological function that increases the amount of air in our lungs and helps to regulate our oxygen levels. This is helpful during times of physical exertion or stress because the body needs more oxygen to sustain itself. Sighing can even be an indication of health. For example, sighing that is accompanied by chest pain can be a sign of a medical condition related to the heart or respiratory system.

There is strong and growing evidence that the outbreath has powerful impacts on health and perceptions of well-being. According to James Nestor (2020), science writer and author of the book Breath, studies show that individuals who have changed their breathing dramatically improved their health. There is also a difference in when we are breathing mindfully and when we are breathing while stressed. These discoveries extend our knowledge of breathing far beyond the idea that respiration is just to keep us alive. Parts of the brain like the somatosensory cortex, a part of the brain associated with touch communicates with the motor cortex to tell us when to inhale and exhale. This may be important to those individuals with asthma or anxiety because these regions may be sensitive to fluctuations in respiration, causing hyperventilation or breathlessness (Herrero-Rubio, et al, 2018).

In the trauma field, there is interest in the vagal nerve, the lungs, and, in particular, the parasympathetic nervous system. In vagal theory, this is the “resting and digesting” part of the nervous system. If we pay attention to our breathing by taking a deep inhale followed by an extending exhale, the parasympathetic system may override a fight-or-flight reaction. Essentially, the longer exhale tells the body and mind to relax—a respiratory pattern familiar to those practicing breath-oriented mediation.

Making a Forced Sigh

One way to really experience a sigh is through a stronger-than-usual outbreath or a “forced sigh.” This specific way of sighing involves taking a deep breath in and then exhaling with a long, audible sigh. In expressive, sensory-based, and body-oriented work, this forced sigh is expanded by emphasizing other nonverbal cues such as facial expressions, gestures, enactments, or body language.

I am currently investigating how different sighs (extended outbreaths) can help children and teachers improve self-regulation and co-regulation in the classroom and support socioemotional learning. In order to do this, I am working with teachers to develop variations of “sigh exercises” combined with expressive arts therapy—movement, enactment, sound, image making, and writing. While learning to make an extended sigh, I believe it is important for our bodies to learn to capture and understand it through multiple senses. Sighing along with movement, vocalization, mark making, and narrative provides a continuum of expression while teaching a powerful practice for stress reduction and the felt sense of personal experiences.

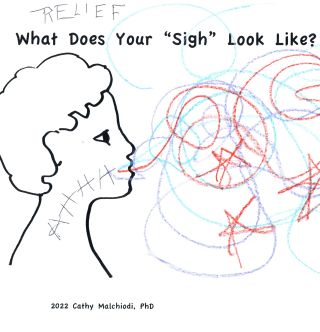

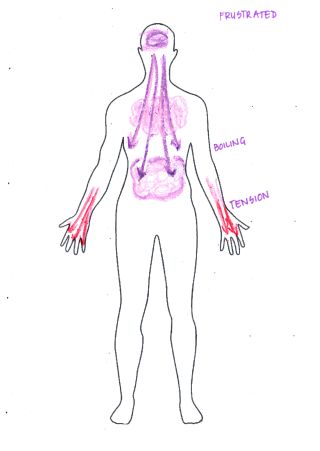

The children I have worked with are excellent researchers, providing feedback through capturing the experiences in colors, shapes, lines, and mark-making (see Figure 1) and storytelling about their art expressions. I can say that the preliminary data collected in the form of art expressions and narratives indicates that teachers are finding benefits in various “forced sighs” focused on various body/mind states. These body/mind states include sighs focused on “tired,” “frustrated,” “content,” and the most popular, “relief.” (Figure 2).

As we continue to explore these variations of sighs, I hope we will begin to understand ways these expressive experiences can specifically support socioemotional learning in children. And for anyone challenged by distress and particularly traumatic stress, I think this research has the potential to expand on how the outbreath helps in reduction of stress and increases body/mind awareness.

Sighing Out the Old, Sighing in the New

A sigh, in the form of an extended outbreath or expanding the experience into an image, sound, or movement, is not a panacea for stress. But I believe regular practice through this type of breathwork and somatically-based expression can be helpful. We can learn to use our outbreath to expel what we no longer want in our bodies and mind. We can also capitalize on this practice to welcome something new—joy, relief, invigoration, enlivenment, and contentment. The point is to know we can apply the power of our own outbreath to access how we feel in the moment or to restore body and mind, simply and mindfully.

References

Herrero JL, Khuvis S, Yeagle E, Cerf M, Mehta AD. Breathing above the brain stem: volitional control and attentional modulation in humans. J Neurophysiol. 2018 Jan 1;119(1):145-159. doi: 10.1152/jn.00551.2017. Epub 2017 Sep 27. PMID: 28954895; PMCID: PMC5866472.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2022). The body holds the healing. Retrieved at https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/arts-and-health/202212/the-body-holds-the-healing.

Nestor, J. (2020). Breath. The new science of a lost art. New York: Riverhead