From Food to Mood

The bugs in your gut have hidden ways of helping you master your emotions.

By Hara Estroff Marano published September 5, 2017 - last reviewed on November 6, 2017

There are more than two pounds of bacteria that make their permanent home in your gut, and scientists increasingly think of them as an auxiliary genome, giving you the DNA for powers that would be hard to pack into your body cells. Cumulatively they carry about 100 times more genes than your already crowded chromosomes. Researchers all over the world are trying to pin down the many ways that the gut bacteria abet human health, a feat that earns beneficial bugs the moniker "probiotics." This much is known for sure: The microbes in your intestines are a diversified lot, and their very diversity is critical for your well-being. That diversity hinges on what you eat.

For most of human history, our ancestors got by on a hardscrabble diet in which nuggets of nutrients came bundled in indigestible plant material. The human gut was adapted to a diet of more than 100 grams per day of fiber from foraged food.

Such fibrous foods travel through the stomach and small intestine intact but eventually meet their match. In the colon, they are fodder for resident microbes, which work over the resistant carbohydrates (known as prebiotics because they enhance the growth of beneficent gut bugs) by fermenting them— releasing energy, gases, and a handful of metabolites called short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

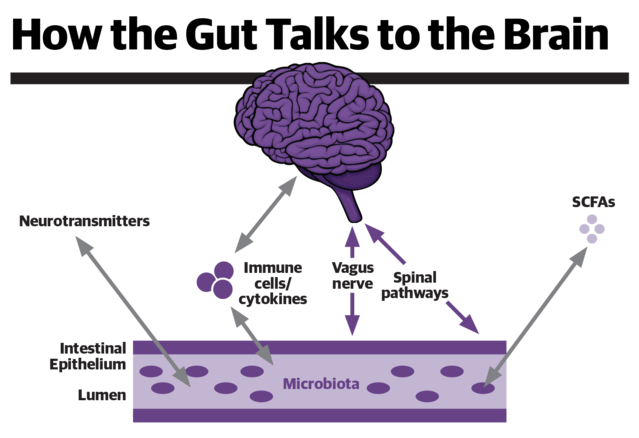

Highly active biologically, SCFAs are one of the many ways the gut communicates with the brain. SCFAs serve as signaling molecules throughout the body—mobilizing hormones and activating nerve pathways and many types of cells to regulate appetite, energy balance, body weight, immunity, brain function, and mood states.

That, at least, is the script. Over the past several decades, the typical Western diet of energy-dense foods has come to supply less than 15 grams of fiber a day. There's mounting evidence that a fiber-poor diet disrupts the balance of gut bugs, drastically curbing production of SCFAs. A lack of SCFAs, scientists say, is a hidden but powerful force behind rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and such psychological ills as anxiety and depression.

"There are genes and products in the microbiome that we absolutely require," says Timothy Dinan, professor of psychiatry at University College Cork, Ireland. "With narrowing of the microbiota, there's a failure to produce certain molecules that are essential to normal brain function."

A flurry of recent research shows, for example, that SCFAs help keep

appetite in check by stimulating the release of satiety peptides in the intestines and sending neural signals to the appetite centers in the brain. Other studies show that specific prebiotics known to boost SCFAs curb the neuroendocrine response to stress, dampening secretion of the hormone cortisol. SCFAs also modulate the way the brain processes emotional information, keeping it from dwelling on negatives.

At the University of Oxford, psychiatrist Philip Burnet and colleagues randomly assigned 45 healthy volunteers to receive one of two kinds of prebiotics—fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) or galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS)—or a placebo every day for three weeks. At the start and the end of the study, they measured cortisol levels for a period after awakening—an index of the neuroendocrine response to stress. Responses to emotionally positive and negative stimuli were also assessed, as an attentional tilt toward negatives is a hallmark of anxiety and depression.

"GOS prebiotic intake was associated with decreased waking salivary cortisol reactivity and altered attentional bias compared to placebo," the researchers report in Psychopharmacology. Those receiving GOS also paid more attention to positive than to negative stimuli.

In his own studies, Dinan has transplanted fecal matter from depressed patients into germ-free rats. "To our amazement," he reports, "we found that they become far more anxious and they develop anhedonia, a key feature of severe depression."

A plant-rich high-fiber-low-meat diet is essential for diversity of the microbiome, observes Dinan. And that maximizes production of SCFAs.

Facts

- The adult human gut microbiota comprises more than 1,000 species and 7,000 strains of bacteria.

- Maintaining diversity of gut bacteria protects against frailty in the elderly.

- Depressed people have far less diversity in the microbiome than do those who are not depressed.

- Consuming the meat of animals treated with antibiotics reduces diversity of the human microbiome.

- It takes less than two weeks for a switch from a good diet to a fast-food diet to induce changes in the microbiota.

- Foods that beget high levels of SCFAs from gut bacteria include Jerusalem artichokes, globe artichokes, onions, garlic, leeks, chicory, and bananas.

- SCFAs serve as key energy sources for the cells that make up the large intestine.

- The most abundant SCFAs are acetate, proprionate, and butyrate.

- Low levels of proprionate and butyrate have been found to contribute to inflammatory processes in the intestines and elsewhere in the body.

- Butyrate is especially important for maintaining the integrity of the gut's barrier function. It also protects against the development of colorectal cancer.

- SCFAs have been found to protect against diet-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome.