Body Image

Where Your Mind Meets Your Body

How do we integrate our bodies with our minds?

Posted November 28, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Seventy percent of people struggle with body image dissatisfaction.

- Body image issues are precursors for mental illnesses.

- Body self-consciousness is rooted in one's brain and gives one the sensation of being who they are, both physically and mentally.

- Neuroscience studies imply that people with body dysmorphia sense their bodies not as they are, but as they think they are.

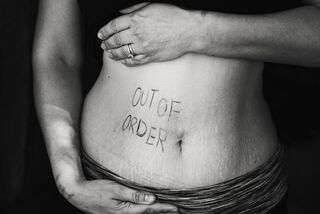

Across the world, people struggle with body image dissatisfaction. From the United States to Brazil to India, it is estimated that 70 percent of people are unhappy with their physical appearance, although the exact reason can differ across genders and cultures1-3.

In some cases, body image dissatisfaction turns into body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) which is characterized by a person’s distorted perception of one’s own body size and looks. BDD is estimated to affect 2 percent of the general population in the United States, but clinicians and researchers believe that the prevalence is greatly underestimated4. One of the major concerns about body image dissatisfaction and BDD is that they often serve as precursors for or symptoms of other mental illnesses, such as eating disorders, anxiety, depression, and even suicide.

It is widely agreed that we are living through a mental illness crisis, a fact that is corroborated by the rising scores of depression and anxiety (even before the pandemic) and the increase in suicide rates, especially among children and young people. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, suicide is 1 of the 3 leading causes of death among 10- to 34-year-olds in the United States, and is most often caused by mental health challenges, such as BDD.

While BDD and body image dissatisfaction (referred to collectively as “body dysmorphia” going forward) by no means affect everyone nor is the sole cause of all mental illnesses, it is an experience affecting the majority of people globally. Thus, improving how people relate to their bodies could be an effective way to counter the rise of mental illnesses.

I only realized body image dissatisfaction was so pervasive when I recovered from my own body dysmorphia which I had struggled with during my eating disorder. While I found it comforting that a certain degree of body image dissatisfaction was normal, I also thought it was very disturbing how disconnected we have become from our own bodies and how much importance we have placed on our appearance. I chose then that I did not want to live like that.

A large part of my current work revolves around helping people figure out how they can reunite with their bodies. I do this through research, coaching, and writing. In this post and future ones, I am diving into the multifaceted roots of how we relate to our bodies and why some people develop body dysmorphia. We will learn about lived experiences, the underlying science, and the most effective treatments.

In this post, I want to address how we got to where we are now: a world of people vexed with their bodies.

Separation of mind and body

Popularly, we talk of our bodies as separate from our minds, in dualistic terms, a concept rooted in the words of 17th-century French philosopher Descartes. This is one of the reasons why we have separated mental health from physical health, although in reality, they are both physical. Sometimes what we think of as physical health (e.g. back pain) is caused by “mental” issues (e.g. stress). One consequence of this dissociation is that our bodies have been removed from our identity, and instead become a tool for recognition.

Body self-consciousness

How do we integrate our body with our mind? In neuroscience, studies have found that body self-consciousness is rooted in our brain and it is what gives us the sensation of being who we are5,6, both physically and mentally. There are three components that make up our body self-consciousness:

- Physical body ownership: This is how you perceive your body from the outside. While the process is subconscious, it can be modulated by conscious input (for example what you see). Electrical stimulation of certain brain areas can manipulate whether a person thinks a body part belongs to them or not.

- Interoception: This is your brain’s way of noticing the sensations that happen inside your body. Interestingly, this is one of the key factors that are dysfunctional in people with body dysmorphia and eating disorders (as well as many other illnesses).

- Cognitive appraisal: This is a conscious process of identifying and labeling our internal sensations. It is through a cognitive appraisal that we construct a “mental idea” of who we are and what we look like. This psychological process is often leveraged in therapy settings to help people change their distorted body images.

Body ownership, interoception, and cognitive appraisal are mediated by both unique and similar brain regions7. This may explain why a person can have a defect in only one component (e.g. body ownership), with consequences for their body self-consciousness. Such phenomena are well-studied in people with distinct brain damage, and we will dive into that in future posts. We know that people with body dysmorphia generally have a reduced ability to notice and label their internal sensations accurately8. In some cases, they may not even identify their body as their own.

How does body self-consciousness go awry in people with body dysmorphia? How did we become so dissociated from our bodies that we can no longer accurately sense when our heart is beating or label how we feel during moments of sadness, happiness, hunger, or thirst?

To tackle these questions, I have addressed research literature, discussed with scientists, and interviewed people that have lived with body dysmorphic challenges. This is what I have learned so far, and rest assured, we will continue to return to these points in future posts:

Suppression of feelings

“I realized that for years, I had completely neglected feeling my body.”—a 25-year-old cancer survivor from Italy

One idea which particularly resonates with me is that body dysmorphia results from a long period of suppressing our feelings, which diminishes our interoceptive awareness. Instead of sensing our internal state, we become reliant on external cues.

A teaser: Experiments have demonstrated that people with eating disorders are more susceptible to sensing a fake hand as their own6. We will dive more into this strange-sounding topic in future posts, but the important message here is that people with eating disorders are less connected with their own bodies, and more likely to depend on what they see (in this case, the fake hand).

This obviously presents a problem, because if they have a distorted visual perception of their body, it is going to be integrated into their body self-consciousness. This vicious loop can maintain people in a state of aggravating body dissatisfaction.

Lack of a mental self-image

“I have always meditated every day. It connects me with my mind and body.”—a 36-year-old woman living in Niger and practicing Muslim

It is also possible that people with body dysmorphia never learned how to sense their internal state. This inability would be a barrier to accurately labeling their feelings and building a mental image of themselves. A lack of a mental image of yourself will hinder interoceptive accuracy and make you more reliant on external cues.

Distorted ideals

“If I had never looked in the mirror, I actually think I would be really awesome.”—an American woman living in Belgium, age 42

Lastly, cultural and societal idealization of body types may distort our cognitive understanding of what a body should look like. Our cognitive appraisal and mental image may constantly point out the errors between ourselves and the cultural ideal, ultimately leading to an exaggeration of our differences which would impair our abilities to notice our internal sensations. This idea seems to resonate particularly well with people who do not “feel at home” in their bodies. Somehow, their body ownership has been lost.

A revealing finding is how fake body parts can so easily and quickly be integrated into our interoceptive awareness and emotional responses9. In other words, our minds can quickly change how we integrate new body parts into our body self-consciousness. This type of result implies that when we are struggling with body dysmorphia, we sense our bodies not as they are but as we think they are. By dissociating our minds from our bodies, our society has shaped our bodies into a product of our minds. But there is a part of your brain that is important for fusing your body with your mind: the anterior insula. Can we leverage the function of the anterior insula to think of our bodies as a part of who we are, rather than a depiction of what we are?

References

1) Ferrari EP, Petroski EL, Silva DA. Prevalence of body image dissatisfaction and associated factors among physical education students. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2013;35(2):119-27. doi: 10.1590/s2237-60892013000200005. PMID: 25923302.

2) Kapoor A, Upadhyay MK, Saini NK. Prevalence, patterns, and determinants of body image dissatisfaction among female undergraduate students of University of Delhi. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022 May;11(5):2002-2007. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1851_21. Epub 2022 May 14. PMID: 35800482; PMCID: PMC9254831.

3) Silva, Andressa Ferreira da et al. Prevalence of body image dissatisfaction and association with teasing behaviors and body weight control in adolescents. Motriz: Revista de Educação Física [online]. 2020, v. 26, n. 1

4) Rief W, Buhlmann U, Wilhelm S, Borkenhagen A, Brähler E. The prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder: a population-based survey. Psychol Med. 2006 Jun;36(6):877-85. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007264. Epub 2006 Mar 6. PMID: 16515733.

5) Blanke, O. Multisensory brain mechanisms of bodily self-consciousness. Nat Rev Neurosci 13, 556–571 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3292

6) Tsakiris M, Tajadura-Jiménez A, Costantini M. Just a heartbeat away from one's body: interoceptive sensitivity predicts malleability of body-representations. Proc Biol Sci. 2011 Aug 22;278(1717):2470-6. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.2547. Epub 2011 Jan 5. PMID: 21208964; PMCID: PMC3125630

7) Salvato G, Richter F, Sedeño L, Bottini G, Paulesu E. Building the bodily self-awareness: Evidence for the convergence between interoceptive and exteroceptive information in a multilevel kernel density analysis study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2020 Feb 1;41(2):401-418. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24810. Epub 2019 Oct 14. PMID: 31609042; PMCID: PMC7268061.

8) Quadt L, Critchley HD, Garfinkel SN. The neurobiology of interoception in health and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018 Sep;1428(1):112-128. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13915. Epub 2018 Jul 5. PMID: 29974959.

9) Ehrsson HH, Wiech K, Weiskopf N, Dolan RJ, Passingham RE. Threatening a rubber hand that you feel is yours elicits a cortical anxiety response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jun 5;104(23):9828-33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610011104. Epub 2007 May 21. PMID: 17517605; PMCID: PMC1887585.