Addiction

Ask The National Institute on Drug Abuse Expert

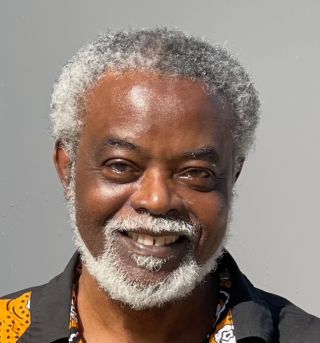

An interview with methamphetamine and cocaine expert, NIDA's Jean Lud Cadet, MD.

Updated March 12, 2024 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

Key points

- Researchers have found important racial disparities in substance use disorders, yet they are often ignored.

- The amount/frequency of methamphetamine use affects possible brain injury and treatment length/success.

- Epigenetic discoveries may help us understand how an occasional drug abuser develops a substance use disorder.

In my last blog, I discussed that methamphetamine (or cocaine), in concert with fentanyl, is often a factor in overdose deaths in the United States. In this interview, I spoke with Jean Lud Cadet, MD, chief of the Molecular Neuropsychiatry Branch at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) in Baltimore, Maryland. He completed training as a neurologist at Mt. Sinai in New York City. He also completed a psychiatry residency at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, where he was a medical student. Dr. Cadet has been the leading researcher and national expert on methamphetamine for nearly forty years. His research has been cited by researchers around the world over 31,000 times, and consequently, he is uniquely qualified to talk about past and current issues with “meth” and other drugs.

Racial Disparities in Substance Use Disorders Are Real But Usually Ignored

Gold: What have been the most important insights you have learned about methamphetamine and other substance use disorders?

Cadet: I have learned substance use disorders (SUDs) are very difficult to treat because of stigmas. I have also learned there are many racial disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of patients suffering from substance use disorders. Yet many clinicians refuse to deal with those facts, which is unhelpful to patients.

Gold: Many people think this is a black/white issue after watching the hit television show “Breaking Bad.” However according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), when it comes to people ages 12 years and older who used methamphetamine in the past year, American Indians/Alaska Natives had the highest abuse rate (2.4%), followed by Native Hawaiians or Other Pacific Islanders (1.1%). SAMHSA also reported an abuse rate of 0.7% for whites and only 0.2% for Blacks. Of course, abuse rates vary depending on the substance. In most cases of abused substances, neither whites nor Blacks have the highest abuse rates.

The question then becomes, why do so many doctors ignore research on racial disparities? It seems important.

Cadet: It is important. Racial disparities exist in the assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of patients presenting with substance use disorders. Many patients are also negatively impacted by attitudinal biases health care providers might abhor subconsciously or consciously. Yet despite literature documenting the existence of racial disparities, SUD professionals are reticent to read that literature or, if they have read these papers, they tend to ignore their contents and suggestions for change.

If health professionals admitted the existence of racial disparities, they would have to acknowledge their lack of cultural awareness and make individual changes in their approaches to SUD patients. More importantly, they would have to address issues relevant to structural racism in medicine. Most physicians and others caring for SUD patients do not appear ready to make substantial alterations in their modus operandi within very conservative structures.

Amount of Methamphetamine Abuse May Cause Brain Injury and Damage

Gold: Do you think methamphetamine-induced psychosis is more like traumatic brain injury (TBI) than a naturally occurring psychosis?

Cadet: The issue is complicated. Not all patients have identical causes for psychosis; any more than patients diagnosed with acute schizophrenic psychosis or acute manic psychosis have identical neurobiological etiologies for their psychotic symptoms. Also, the similarities of methamphetamine-induced psychosis to traumatic brain injury depend on the amount of methamphetamine patients were exposed to. This is manifested by the clinical course of methamphetamine-induced psychosis. Some patients have remitting and relapsing courses with negligible evidence of cognitive deficits, while others have progressive cognitive disabilities, and still others show profound cognitive deterioration. A case could be made that patients in the progressive cognitive disabilities group might have taken enough of the drug to develop neuropathological changes in the brain, somewhat akin to TBI. This is partly supported by studies of patients exposed to methamphetamine showing significant abnormalities in their neuroimaging findings. In addition, post-mortem studies have identified neuropathological changes in various regions of the brains of users of large doses of methamphetamine.

My colleagues and I have reviewed the literature on neuropathological changes associated with methamphetamine and other drugs. Methamphetamine users have evidence of structural abnormalities in their brains. They also have a smaller hippocampal volume and exhibit altered white matter tissue integrity in the frontal cortex, corpus callosum, and perforant pathway. These findings implicate brain dysfunctions that must be taken seriously when evaluating patients and making treatment recommendations.

For example, a person with methamphetamine psychosis should not be treated with older antipsychotics like haloperidol because these patients are more at risk for motor abnormalities triggered by older antipsychotics. The risk is lower with newer antipsychotics.

Psychedelics, Including Psilocybin, May Be a Future Treatment for Methamphetamine Use Disorder

Gold: What do you think about psilocybin (“magic mushrooms”) for treating methamphetamine use disorder?

Cadet: Psilocybin is a non-addictive psychedelic agent shown to provide beneficial effects in cases of depression, anxiety, and alcohol and nicotine use disorders. Given there is no FDA-approved medication for methamphetamine use disorder, it is important to support trials of psilocybin-assisted therapy for this brain disorder.

Future Discoveries

Gold: What do you think will be the most significant discovery in addiction science in the next few years?

Cadet: I feel the biggest discoveries will be in epigenetics, which explains how behaviors and the environment may cause changes affecting how genes work. Epigenetics will provide a paradigm for understanding what triggers or affects the elevation from occasional use in some patients to continuous abuse. The All of Us research program is one major mechanism that could be used to help attain these goals.

Gold: I consider you a genius. But how has your family impacted your career and current level of success?

Cadet: I have always wanted to be a physician as far back as I can remember. This is probably because my mother worked as head of a pharmacy in a hospital in Limbe, Haiti. The hospital was a missionary hospital that cared for everyone regardless of their ability to pay. My parents, especially my mother, supported my goal and supported my education by enrolling me in the best secondary school, College Notre Dame du Perpetuel Secours in Cap-Haitien on the northern side of Haiti. My mother always said hard work pays off and provided the example I have followed.

Cadet’s Most Important Research Papers

Gold: What are your most important papers MDs, researchers, and parents and family members should read?

Cadet: I view SUDs as brain disorders with a significant underlying inclination to look for their neurological impact on all patients. I suggest reading these classic papers:

Cadet JL, Bisagno V, Milroy CM. Neuropathology of substance use disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2014 Jan;127(1):91-107.

Jayanthi S, McCoy MT, Cadet JL. Epigenetic Regulatory Dynamics in Models of Methamphetamine-Use Disorder. Genes (Basel). 2021 Oct 14;12(10):1614. doi: 10.3390/genes12101614.

IN Krasnova, JL Cadet Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death. Brain research reviews 60 (2), 379-407.

References

Cadet JL, Jayanthi S, Deng X. Speed kills: cellular and molecular bases of methamphetamine-induced nerve terminal degeneration and neuronal apoptosis. FASEB J. 2003 Oct;17(13):1775-88. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0073rev. PMID: 14519657.

Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Sugihara G, Takei N, Yoshikawa E, Nakamura K, Iwata Y, Tsuchiya KJ, Suda S, Suzuki K, Kawai M, Takebayashi K, Yamamoto S, Matsuzaki H, Ueki T, Mori N, Gold MS, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine causes microglial activation in the brains of human abusers. J Neurosci. 2008 May 28;28(22):5756-61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1179-08.2008. PMID: 18509037; PMCID: PMC2491906.

Cadet, JL. , Gold, MS Methamphretamine-induced psychosis: Who says all drug use is reversible? Current Psychiatry. 2017. November 16(11)14-20.