Psychiatry

Rachel Aviv’s Search for the Meaning of Mental Illness

An interview with the author of "Strangers to Ourselves."

Posted May 20, 2024 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Rachel Aviv’s book "Strangers To Ourselves" explores how psychiatric diagnoses intersect with identity needs.

- She also considers how our desire for certainty can obscure the complexity of human suffering.

- The language and concepts that we use to describe mental illness can help, or hinder, our ability to heal.

All of us struggle with challenges that can negatively impact our mental health. But a smaller portion of us will experience mental health crises that lead us to psychiatrists or other mental health professionals, and perhaps to an official diagnosis.

Major depressive disorder. ADHD. Bipolar disorder. Borderline personality disorder. Anorexia nervosa. Autism. Schizophrenia. These names are powerful. For some, they provide welcome relief. They give us a sense of understanding and hope.

But for others, they feel like a prison sentence. Diagnoses like depression, anorexia, or schizophrenia sometimes lead people to think that something deep within them is “broken”—which can perpetuate stigma and pessimism. Some, like borderline personality disorder, can feel like a moral condemnation. These names can be particularly problematic when the normal crises of adolescence—social isolation, self-doubt, anxiety—are misconceived as mental disorders.

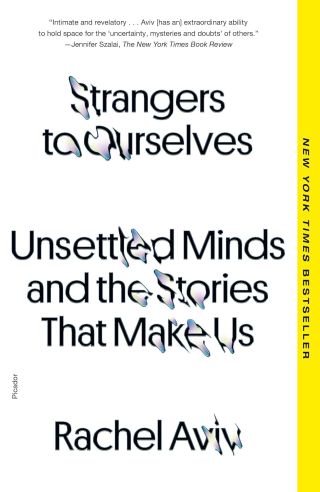

I spoke with Rachel Aviv, New Yorker staff writer and author of the bestselling and critically acclaimed Strangers to Ourselves: Unsettled Minds and the Stories that Make Us (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2022) Her thoroughly researched book tells the stories of how five people, from different cultures and communities, struggled to make sense of their diagnoses. The first story is about her own diagnosis, at the age of 6, of anorexia. Her book is an urgent and timely reflection on the power, and hidden costs, of psychiatric language.

Justin Garson: When I first read your book, I read it as a critique of the way that psychiatric categories don't just offer diagnoses, but identities—and how embracing these identities can cause unintentional harm. But after rereading it, I started to feel like it was more of an exploration of the very human need for identity as such. To what extent is your book a critique of psychiatry's ready-made identities, and to what extent is it an exploration of our basic need for identity?

Rachel Aviv: I definitely prefer the latter reading. Given how we need stories, containers, frameworks: have we sufficiently recognized how powerful psychiatric language and explanations are in fulfilling that need? When we are on that search and we’re handed this explanation of who we are (“depressed,” “bipolar,” whatever it is), have we thought enough about how that very human need for definition—combined with the vulnerability of whatever state led to the diagnosis—makes us susceptible to defining ourselves, perhaps too rigidly or faithfully, through that lens?

JG: That makes a lot of sense. Something like depression isn’t just a diagnosis like diabetes, but it’s a form of existence.

RA: I think there is this belief and hope that it is just like diabetes. And of course for people with diabetes, that might become an identity, too. But I think this common trope—“mental illness is a disease like any other,” “taking antidepressants is just like taking insulin”—is overlooking a very fundamental fact: The organ that makes sense of the world and makes sense of who we are is also the one that is directly affected.

JG: You write about being diagnosed with anorexia at the age of six, and being hospitalized for six weeks. A question you ask in your book is whether you were able to recover, in part, because you were too young to make the label the “defining fact” of your life. You didn't have any expectation that this was a permanent part of your identity that you’d always be struggling against. What are some lessons for how we, as a society, talk and think about mental health?

RA: One thing that may have helped is that the hospitalization was always seen within my family as a crisis. They talked about it like “Rachel is having a crisis,” versus “Rachel has an illness.”

When I asked a friend, Alice Gregory, who has also written about anorexia, to read a draft of that chapter, she made a really helpful observation that I tried to incorporate into my revisions: There was a certain kind of irony and almost dumb luck that I was a little too young for that word, “anorexia,” to have social cache and social traction. I’d never heard of the word, and it just didn't stick to me. It wasn't meaningful to my friends. It wasn't something that was shared at school. It was rejected by many adults in my life because they didn’t think the word made sense for a 6-year-old.

JG: I like the idea that it can be better to talk in terms of a “crisis” rather than in terms of an “illness.”

RA: It's hard because I think it could go the other way where there are people who say, “I don’t want to take medications, I don’t need lithium, that was just a crisis and it’s time-limited.” So I don't know that that takeaway is universal.

But I think during the first appearance of an illness, it is worth being open to the possibility that individual susceptibilities interacted with environmental factors in a very particular way, and if the environmental triggers are better controlled or dealt with the diagnosis doesn’t necessarily need to be seen in terms of lifetime prognosis.

JG: An ongoing theme in your book is uncertainty. Am I sick or am I having a spiritual crisis? Is my sadness due to a bad childhood or a chemical imbalance? Rather than answer them for us, you invite the reader to linger with these questions. Is there a virtue in just being able to sit with uncertainty and multiple interpretations?

RA: I do value the ability to let ambiguity exist—to sharpen one's understanding of the ambiguity without trying to resolve it. I admire that in general as an ideal in writing and otherwise.

But I felt like I didn't have a choice with this subject. There was no clean argument. If there had been, I probably would have gone for it. Each story that I told seemed to suggest a certain set of ideas and conclusions. But as soon as I would move to the next chapter, it would complicate whatever conclusions the previous one had gestured toward.

One of the few things that did feel clear in this realm was that to behave as if one knows the one certain answer in this field ends up looking like hubris. The field itself has swung from one position of certainty to another for a long time, and I think now we’ve finally reached a point, at least to some degree, where people are generally a little more open about recognizing that multiple frameworks and approaches are necessary. But I really felt like the material itself prevented me from getting to a place of certainty.