Parenting

Parenting Adolescents and the Power of Saying "No"

It can be hard to say "no," but life gets harder if you can't.

Posted June 1, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- The ability to say "no" can help both parents and children protect their self-interest in relationships.

- Adolescents who say "no" can aggravate their parents, but these teenagers may also be skilled at setting boundaries with their peers.

- Parents often set limits with their child's welfare in mind, so it can be helpful to consistently explain their decisions.

Consider some of the powers of saying “no.”

In relationships, stating “no” can be used to argue with, to protest about, to refuse, to defend, or to block something unwanted from going on.

- “No, I disagree!”

- “No, that’s wrong!”

- “No, I won’t do this!”

- “No, I didn’t say that,”

- “No: stop doing this to me!”

The Necessity of Saying “No”

“No” is a powerful, limit-setting word that protects self-interest in relationships. Without the capacity to say “no,” a young person’s wellbeing can be unguarded. “No” is every person’s primary defender.

Although “no” may not be popular to say or easy to say, it's often necessary to say during the push and shove of adolescence. “I told my boyfriend to stop, he got angry, and now we’re not dating anymore!” “No” can have social consequences.

It does a teenager no favor to be taught that “no” is the opposite of “nice,” to be raised and praised as someone who is always agreeable, never complains, pleases at all costs, goes along to get along, bows to disagreement, and suffers dissatisfaction in silence.

In a world of risks, temptations, and social pressures, parents want to raise a young person sufficiently armed with the power of saying “no” so that safety and healthy self-interest will be protected. “We’re glad he stood up against the bullying, even though we’re sorry that you had to do it at all.”

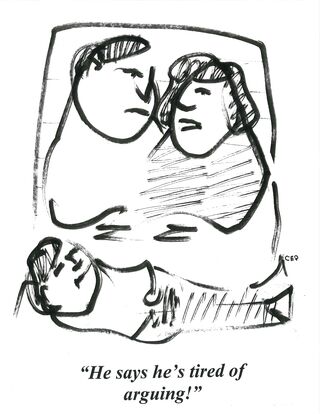

The Aggravation of Saying and Hearing "No"

All this being said, parents tend to be less enthusiastic about this negative declaration when it is used with them. “We want our adolescent to be able to say ‘no,’ just not so often with us!” The adolescent “no” challenges their authority. It opposes what they want.

So, it can be a frustrating adjustment for parents when their mostly compliant ("yes" saying) child becomes a more resistant ("no" saying) adolescent. Now passive resistance like delay, and active resistance like argument, can become more frequent: “Her constant disagreement can be exhausting to live with!”

The child grew up in the Age of Command, believing that parents had the power to make them and stop them. “My parents are in control.” The adolescent, however, has entered the Age of Consent, and now understands that parents can’t make or stop them without the young person’s cooperation. “To get what they want, my parents need me to go along.”

For parents feeling aggravated by adolescent resistance, it's worth remembering this: The teenager who dares to express “no” to the family powers that be (the parents) is often more practiced with setting limits and saying “no” to friends. “He’s no pushover with us, so we’re confident he can stand up to his peers.”

Also, when feeling frustrated by the adolescent “no,” it can help to understand how the adolescent often feels frustrated too. Pushing for more freedom of operation, she or he increasingly encounters the parental “no” as desired permission or provision is refused. “They never let me do anything!”

For an adolescent, pushing for more freedom to grow, a parental “no” can be hard to take. Understanding this, parents can promise: “We will be firm where we have to, flexible where we can, explain our decision, and always want to hear whatever you have to say, so long as it is said in a non-hurtful and respectful way.”

When an adolescent “no” is expressed or a parental “no” is challenged, a conversation needs to begin. “No” is often worth talking about.

The Protection of the Parental “No”

Although sometimes angrily accused of being on a “power trip” by an adolescent whose want has been denied by a parental “no,” parents often forbid with the young person’s welfare in mind. Thus when giving an important “no,” parents need to explain themselves.

For example: “You are not allowed to drink or drug when you are driving. Here is why. As substance use alters your mood it affects your mind—your perception, reactivity, and judgment. Driving a car is a very dangerous activity that kills close to 40,000 people a year, so it requires all your sober attention to keep it safe. Any driving you do must be alcohol and drug-free.”

When Parents Won’t Take “No” for an Answer

When a parent feels that they won’t and shouldn’t take “no” for an answer, they can believe and behave like no difference of opinion will be tolerated, no argument should be allowed, and any disagreement must be punished. And now, parenting is at risk of becoming dictatorial.

At worst, a dictatorial parent can not only shut down open and honest communication, but this domineering behavior can have lasting effects on their growing teenager.

In the extreme, living with such a parent can pose a couple of formative risks, affecting how an adolescent might be prone to act in later relationships. Identifying with the dictatorial parent, the young person may be predisposed to act commandingly forceful: “You will do as I want!” Or, adjusting to the dictatorial parent, the young person may be predisposed to act submissively compliant: “Better to give in than to make a fuss!” In the first case, they can be at risk of abusing, in the second of becoming abused.

A simple “no” can be a very complicated, but very necessary, word to say.