Friends

How is Meaning in Life Different from Self-Actualization?

Some important distinctions between different kinds of self-fulfillment

Posted June 26, 2017

Imagine that you were doing your best to find meaning and purpose in life. What exactly would you be doing? Think about that for a minute, and write down your answer.

Now look at what you just said. To what extent would your activities be linked to:

- Self-Protection (keeping yourself safe from physical harm),

- Disease Avoidance (keeping yourself healthy, avoiding illnesses)

- Affiliation (making friends and allies, maintaining friendships, being accepted, being part of a group),

- Status-Seeking (pursuing prestige and/or dominance, being well-regarded by your peers),

- Mate Acquisition (finding someone to have a romantic relationship with),

- Mate Retention (maintaining a romantic relationship with your partner, holding on to your romantic partner),

- Kin Care (taking care of your own children [or perhaps nieces, nephews, family in general], spending time with your family).

In my last blog, I asked a similar question, but with a very important twist –what you would be doing to become self-actualized (or to fulfill your highest potential).

When asked about self-actualization, research participants in a recently published study were most likely to describe activities that were linked to achieving status. But when it came to eudaemonic well-being (or finding meaning in life), their answers were a bit different.

Here are some examples of what our research participants said they’d be doing to find meaning and purpose in life:

- “To better achieve meaning and purpose in my life, I would be reaching out to the world more, like volunteering.”

- “Providing a great home and life for my children.”

- “Working with animals, saving animals that are abused/neglected, supporting people in need, donating money to those in need, trying to make the world a better place.”

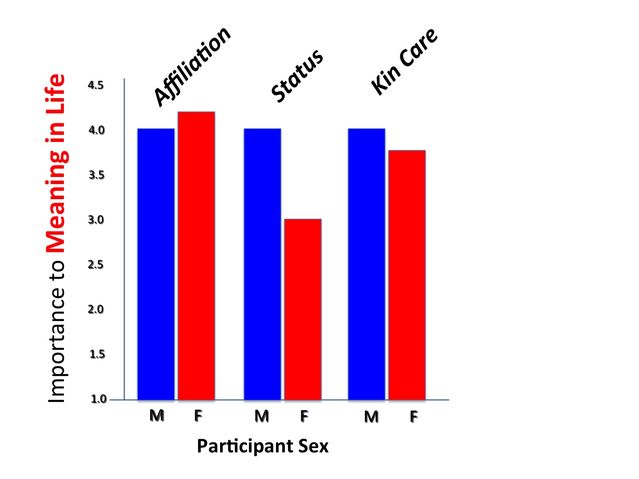

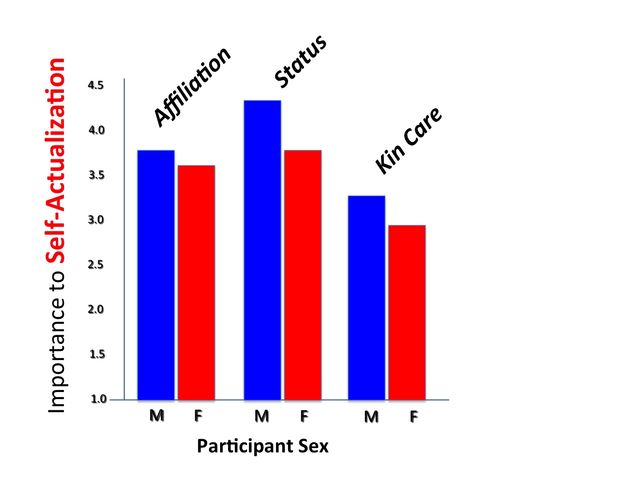

In the two figures below, you can see some of the results reported in a recent paper by Jaimie Krems, Rebecca Neel, and I in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. I’ve picked three of the motives that differed when people thought about what they would be doing to pursue meaning in life as compared to self-actualization.

For self-actualization, or fulfilling one’s highest potential, status-seeking was first on the list, especially standing out for men, but also important for women. For meaning in life, on the other hand, affiliating with one’s friends and caring for one’s kin rise to the top of the list, and status drops in relative importance for both sexes, especially for women.

So, the bottom line is that finding meaning in life is, for most people, primarily about making and maintaining our connections with others. And it isn’t the same thing as self-actualization, which is more linked to winning other people’s respect and esteem.

The central importance of social connections to people’s sense of a meaningful life is comforting. It fits nicely with other findings on the positive side of human psychology, such as research showing that people who spend their money on others are happier than those who spend on themselves (Dunn, Aknin, & Norton, 2008; see: Are you spending money in ways that make you unhappy?) A while back, I asked several people who I regard as having led especially meaningful lives for one bit of wisdom to pass on to my young son. The most common answer from these very productive people was not “kick ass and do anything you can to fight your way to the top,” it was instead: “be kind to others” (see: Overcoming the 5 obstacles to kindness).

Evolved to be selfish?

There’s a broader intellectual point in these findings. Some academics used to worry that thinking about human beings in evolutionary perspective, with its emphasis on selfish genes, would necessarily lead to an emphasis on the negative and self-centered side of human nature. But selfish genes don’t necessarily produce selfish organisms. Taking an evolutionary perspective on our species has made it clear that natural selection favored many positive and prosocial traits in our species: our ancestors always lived in groups, and they survived by cooperating with one another, caring deeply about their friends and relatives, and acting in ways that made others care about them. Indeed, not only did we evolve big brains that want to understand the meaning of life, we evolved big hearts that find the most meaning in taking care of others.

Douglas Kenrick is author of:

The Rational Animal: How evolution made us smarter than we think and

Sex, Murder, and the Meaning of Life: A psychologist investigates how evolution, cognition, and complexity are revolutionizing our view of human nature.

Related blogs:

Do you have to be self-centered to be self-actualized? How would you reach your highest potential?

Rate yourself on the new motivational pyramid

Rebuilding Maslow’s pyramid on an evolutionary foundation

Overcoming the 5 obstacles to kindness

Are you spending money in ways that make you unhappy?

How to spend your way to happiness. The best things in life are…?

References

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319 (5870), 1687-1688.

Krems, J.A., Kenrick, D.T., & Neel, R. (2017). Individual perceptions of self-actualization: What functional motives are linked to fulfilling one’s potential? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. In press