Cognition

Thinking Like a Pig

Pigs show sophisticated cognitive flexibility on a video game task.

Posted February 16, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

It’s easy to underestimate the intelligence of pigs. Most of us haven’t had much experience actually interacting with them, so all we have to go on are stereotypes about their supposed dirtiness and laziness.

But researchers who work with pigs, as well as farmers who raise them, know these animals are capable of various types of complex learning. Over the past twenty years, investigations of farm animal cognition have increased, raising questions about their care and management, as well as our ethical obligations toward them.

Video Game Hogs

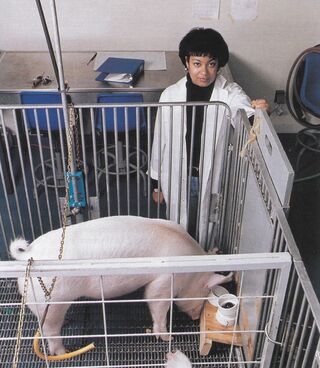

In a new study, pigs demonstrated remarkable mental and behavioral flexibility on a task that wasn’t designed for their species. Candace Croney, a professor at Purdue University and director of the Purdue Center for Animal Welfare Science, along with colleague Sarah Boysen, taught four pigs to play a video game with a joystick. The pigs’ performance, though it did not rival that of dexterous primates, shows they possessed a conceptual understanding of the task.

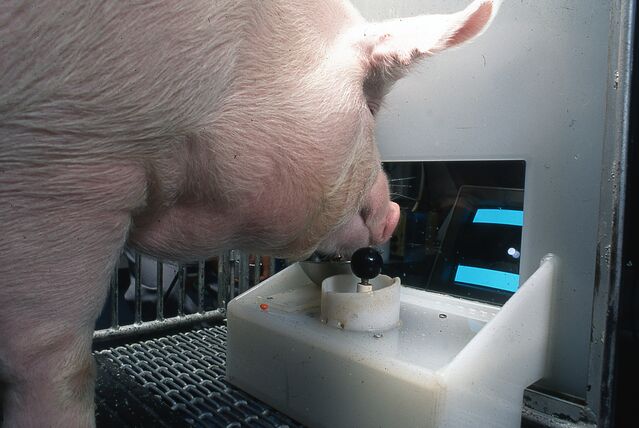

The subjects, two Yorkshire pigs named Hamlet and Omelette and two Panepinto micro pigs named Ebony and Ivory, were first trained to approach and manipulate a joystick with their snouts. Croney says they decided to try the joystick interface since pigs are known for rooting with their snouts — only to realize that people do not actually manufacture joysticks that are ready-made for farm animals.

“We had to mock-up different versions of equipment that pigs would be able to manipulate with their snouts,” she says. “There was a lot of testing to see what would work.”

The experimental apparatus that Croney and Boysen arrived upon consisted of a computer with a color monitor positioned behind a transparent window connected to a modified joystick shaft attached to a gear shift knob. The system was also connected to an automatic food pellet dispenser.

Croney says the pigs were shockingly easy to train. “I had experience training dogs to perform different operant learning tasks, and we used the same sort of approaches here: luring the pigs over and rewarding them for coming near the equipment, then eventually touching the equipment, and gradually shaping their behavior until they were being rewarded for moving the joystick,” she says.

The next step was teaching the pigs how to play a video game using the joystick. It began with a blue border along the inside edges of the computer screen, which created four target walls. The pigs’ job was to move a cursor in the center of the screen in any direction to contact one of the target walls. If they succeeded, they received a food reward, as well as verbal encouragement and pats from an experimenter.

From there, the task became more challenging, as sides of the border disappeared, presenting the pigs with only three, two, or one target wall to hit.

This task was designed for, and mainly been tested on, primates known for their dexterity. Once primates understand the conceptual aspect of the task, they tend to make very few errors.

Pigs, on the other hand, performed well above chance, but not as well as primates. Croney and Boysen say the fact that the task was not designed to work with the anatomy of a pig turned out to be a bigger limitation than they originally anticipated.

“The pigs seemed able to make the connection between the movement of the joystick and the cursor and understand the task they were being asked to perform,” Croney says. “What was harder for them was the consistent, smooth operation of the joystick. That is to say, the pigs were, unsurprisingly, far less dexterous than primates.”

Still, Croney and Boysen say that these far-sighted, hoofed animals could succeed to the degree they did at the task is itself a remarkable indication of their cognitive and behavioral flexibility.

Pig Appreciation

Although the pigs were rewarded for correct answers with food pellets, social motivation appeared to play a huge role in their performance, as well. Croney, who was the primary caretaker and trainer of the pigs, noted that even when the food dispenser jammed and stopped delivering treats, the pigs would continue to work at the task if she continued delivering praise and pets in response to correct answers. At other times, when the task seemed most challenging for the pigs and resulted in their reluctance to perform, only encouragement from Croney was effective in helping them persevere and continue training.

“It was very rewarding to know that you could facilitate learning and mitigate stress for these animals with very simple engagements that they told us they found positive because they would solicit them,” she says.

Croney also noticed that her four pig subjects were unique individuals with different levels of attention and motivation and differing thresholds for tolerating what was being asked of them.

“It was very much like classroom teaching; they each learned at their own pace,” she says. “I came out of this with a much bigger appreciation for the species and the individuality within the species.”

Though Croney and Boysen say this might not have been the best task to investigate cognition in pigs, they still gained insights into pig cognition and learned more about designing tests of cognition for other species.

“We as scientists need to think about the assumptions we make about what animals can or cannot do,” Croney says. “It could be that we simply have not found the right paradigm to ask them the question in a way that allows them to tell us the answer.”

Finally, Croney hopes that her work, and other research exploring the mental abilities of farm animals, has an impact on animal welfare.

“Much of the time, we take for granted the experiences these animals are having, in part, because of a lack of research in these areas,” she says.

“What’s important to me are the ethical implications of taking animals under our care. We should as much as we can about them. They have value outside of any benefit we can derive from them.”

References

Croney CC and Boysen ST. (2021). Acquisition of a joystick-operated video task by pigs (Sus scrofa). Frontiers in Psychology 12:631755. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631755.