Health

Your Brain Relies on Your Heart for More Than Blood

Take care of your heart—it has your brain's ear.

Posted June 13, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- The brain relies on input from the heart to generate mental processes.

- The heart's role in psychological processes is not limited to those involving stress or emotion. It also includes cognitive functions.

- Cardiovascular disorders have negative effects on mental activity as a result of their effects on the brain.

- It appears that aerobic activity may allow people to benefit more from the heart's role in mental functioning.

With the brain getting a lot of attention during Alzheimer's and Brain Awareness Month, here's a surprise quiz: Which organ of the body is second only to the brain in its psychological importance?

By psychologically important, I mean it influences mental processes and provides researchers with tools for investigating them.

If you hadn't seen the title of this post, you probably would have had trouble coming up with an answer.

As you are probably aware, ancient philosophers attributed numerous psychological functions to the heart that are now known to be brain functions. But there is growing scientific recognition that the cardiovascular system causes, participates in, and reflects psychological phenomena. This research comes under names like brain-heart interaction, neurocardiology, and cardiovascular psychophysiology.

One very important mental function is threat evaluation. It is essential for survival for us to judge accurately whether a stimulus, event, or decision is favorable or unfavorable to our wellbeing. The heart may play an important role in this capability.

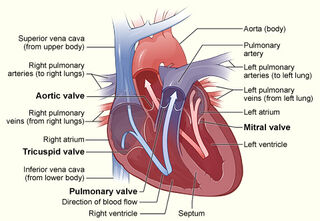

The cardiovascular system appears to be sensitive to the difference between a challenge and a threat (Blascovich, Mendes, Vanman, & Dickerson, 2011). This distinction rests on whether a person perceives that they have the resources necessary to cope successfully with a demanding situation. If so, it is experienced as challenging; if not, the result is threat. It has been shown that challenging situations produce cardiovascular adjustments reflecting more forceful contractions of the heart, whereas threatening situations evoke a response pattern dominated by constriction of blood vessels.

In much of this research, it is not clear whether the cardiovascular system influences or merely reflects the perception of threat and challenge. But there is reason to believe the heart can causally influence mental functions. For example, research suggests that the increase in blood pressure produced while the heart is contracting stimulates pressure-sensitive receptors ("baroreceptors") in blood vessels. These signal brain centers in such a way that, for example, an image of the facial expression that accompanies disgust is judged to be more intense while the heart is contracting than when presented in the time between contractions when blood pressure is lower (Gray, Beacher, Minati, Nagai, Kemp, Harrison, & Critchley, 2011).

The heart's influences on mental processes are not limited to the evaluation of incoming stimuli. Memory is another critical cognitive function that may reflect cardiac activity. Research suggests that stimuli to which subjects had previously been exposed are judged to be more familiar when presented during heart contractions than when presented while the heart is relaxed (Fiacconi, Peter, Owais, & Köhler 2016).

There is even a research tool, the heart-evoked potential, which is a measure of the brain's bioelectrical response to heart contractions that provides an indication of neural processing of cardiac activity.

Sound Body, Sound Mind

If brain functions normally reflect input from the heart, what is the effect of cardiovascular disease? Hypertension, a condition involving chronically elevated blood pressure, is a major risk factor for stroke, which can occur when it causes damage to blood vessels that supply the brain. And that damage can have a major impact on the brain's capacity for both mental and physical activity.

But it turns out that even in the absence of stroke, hypertension may impair brain functions, thereby promoting cognitive decline. Research on this problem has examined a variety of mental processes, including attention, processing speed, and memory. So, controlling high blood pressure works not only to reduce the risk of cardiac events but also to preserve cognitive functioning.

Hypertension may also affect pain perception. In many ways, it is correct to say that pain happens in the brain. But pain involves more than the detection of bodily sensations by the brain. There is evidence to suggest that pain is modulated by cardiovascular activity. For example, it appears that sensitivity to pain is reduced in hypertensive individuals. Although pain is generally unwelcome, it obviously can promote survival by alerting us to possible physical danger or damage. This is especially important in hypertensive individuals, who have elevated risk for cardiac events and, at the same time, may be less sensitive to cardiac pain stemming from those events that might otherwise alert them to possible myocardial infarction.

We Were Born to Run; or Bike or Swim; or, at Least, to Walk

There's a theory that we have the capacity for long-distance running because the survival of our hunter ancestors was facilitated by their ability to catch prey, not by being faster, but through greater endurance. Nowadays, catching a meal on the run more likely involves a fast food restaurant or a microwave oven. But there is another reason to build up our ability to cover long distances through our own physical exertion: It appears that aerobic conditioning promotes brain health. Physical exercise may stimulate the growth of new brain cells and seems to have a range of positive effects on brain functioning. We probably more often think of exercise as a means of weight control. But if that isn't enough to motivate you to up your exercise game, consider the benefits of a healthier brain and possible consequences not only for cognitive function but also for avoiding mental health problems such as anxiety and depression that reflect the health of our brains.

It must be pointed out that much of the research on brain-heart interactions is in the early stages. As a result, practical applications are largely experimental. For example, there is a lot of interest in the vagus nerve of the parasympathetic nervous system as an "information highway" responsible for communication linking the brain to the heart as well as to other bodily organs. Some research involves the use of biofeedback or direct stimulation to increase vagal activity as a means of improving mental and physical functioning. This has encouraged the development of various commercial products marketed as a way to tune up the vagus as a means of achieving all kinds of psychological as well as biological benefits.

It may be premature to embrace these products with high hopes for practical payoffs. However, research on brain-heart interactions does lead to a few useful suggestions. One is that it provides an additional reason, if you need one, to be aware of and maintain cardiovascular health since it is relevant not only to heart disease but also to brain function. Another is that while adjectives such as “holistic”, terms such as “mind-body connection”, and expressions such as “healthy mind in a healthy body” can seem rather vague, there is good science that bears out the underlying premise. And it might be of interest to revisit the writings of ancient philosophers, who were prescient in many ways long before the scientific method came into being.

References

Blascovich, J., Mendes, W.B., Vanman, E. & Dickerson, S. (2011). Social Psychophysiology for Social and Personality Psychology. London: Sage.

Fiacconi, C. M., Peter, E. L., Owais, S., & Köhler, S. (2016). Knowing by heart: Visceral feedback shapes recognition memory judgments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(5), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000164

Gray, M. A., Beacher, F. D., Minati, L., Nagai, Y., Kemp, A. H., Harrison, N. A., & Critchley, H. D. (2012). Emotional appraisal is influenced by cardiac afferent information. Emotion, 12(1), 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025083