From Fear to Guts: How the Microbiome Fights Anxiety

The microbes in your gut influence how you respond to stress. How you nourish them may determine whether or not you develop anxiety.

By Devon Frye published December 17, 2019 - last reviewed on September 28, 2020

If ever there was one, this is an Age of Anxiety. As many as 1 in 5 Americans struggled with an anxiety disorder in 2007—and more recent data suggest that worries have only worsened in the years since. According to an American Psychological Association poll, nearly 40 percent of adults felt more anxious in 2018 than one year prior.

The search for effective remedies has long focused on the brain because it is believed to be the puller of all strings, the major go-between with the outer world. But that view is shifting, specifically toward the gut and the array of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiome, that inhabit it. Recent studies suggest that the microbiome not only plays a significant role in the development of anxiety, it may also open paths to treatment—and ultimately, perhaps, prevention.

The billions of bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract dwell in a complex ecosystem where they complete the process of digestion and perform many other tasks helpful to their human hosts. They thrive on undigested food and churn out some useful metabolic byproducts, including short-chain fatty-acids (SCFAs), created from “undigestible” carbohydrates, and tryptophan catabolites (TRYCATS), breakdown products of the essential amino acid tryptophan. SCFAs are important signaling molecules in the nervous system and brain, and tryptophan aids production of the neurotransmitter serotonin.

“The gut bacteria are like mini factories,” says Gerard Clarke, a psychiatrist at Ireland’s University College Cork and a researcher at APC Microbiome Ireland. “There’s so much production going on in your digestive tract.” A healthy, diverse microbiota—formed through a lifetime of exposure to beneficial bugs and a nutritious diet—generates a steady supply of SCFAs and TRYCATS to bolster the integrity of the gut and its operations.

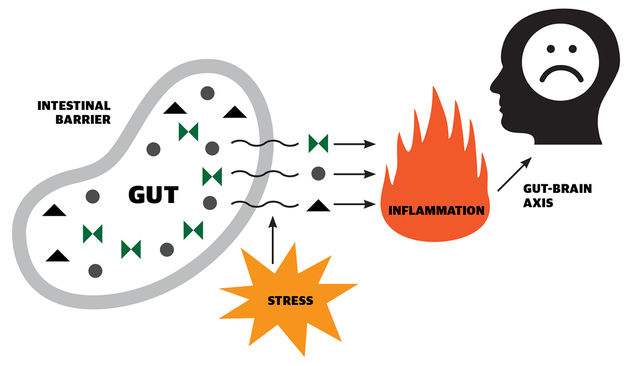

Stress, however, throws a wrench in the gears. According to a review published in 2019 in the Journal of Neuroscience Research, exposure to stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and the cascade of hormones released can, among many other actions, increase the permeability of the intestine. Toxins may then leak from the gut into the bloodstream, triggering an inflammatory response. Inflammatory substances can travel to the brain via nerve pathways connecting brain and gut.

The stress-induced neuroinflammation may spark anxiety, says study author Karina Alviña, of Texas Tech University. A precise chain of causality has not yet been established. “Right now, we mostly have correlations,” Alviña says. “But we think there is a really close relationship between the microbiome, the immune system, and increased vulnerability to developing anxiety.”

Researchers are still unsure what the exact bacterial composition of an anxiety-resistant microbiome would look like, but “we do know that diversity is consistently associated with health,” says Clarke. Gut diversity can be improved through diet—especially fibrous vegetables or fermented foods like yogurt and sauerkraut. It can also be boosted by consuming specific “good” bacteria, or probiotics. Clarke’s research suggests that supplementing one’s diet with certain probiotics may be able to inhibit the release of cortisol, weakening the stress response that leads to anxiety.

In a recent review reported in General Psychiatry, of 15 studies using probiotics to treat anxiety, five showed a positive effect. Such evidence may not seem dramatic, but because each person’s microbiome is unique, Clarke says, it’s not always clear which bacterial strains are best. “It’s not an umbrella thing that all probiotics do. The effects are strain-specific.” His lab and others are attempting to zero in on the most anxiolytic strains.

“The microbiome has really changed the way that we see neurological disorders,” says Alviña. “Maybe the brain doesn’t control everything.”

What Makes Your Microbiome?

The microbiome is already forming by the moment you’re born. “In a natural delivery, the newborn is exposed to the vaginal microbiome,” Texas Tech’s Karina Alviña says; those born via C-section don’t pass through the same environment. That difference, and others, could affect gut composition for life. Other factors that influence the microbiome include:

Infant feeding method:

Microbes in breast milk seed the infant’s microbiome, psychiatrist Gerard Clarke says. “Being breastfed seems to get us on the right track for good mental health later.”

Socialization:

Other people are just like us—covered in germs. Increased exposure to others in early life is associated with a healthier microbiome, according to a 2016 review.

Outdoor exposure:

Soil microbes may guard against mental health challenges, a 2007 study found. Says Clarke: “Less access to greenspace may mean less microbial content.”

Antibiotic use:

Antibiotics kill harmful bacteria. But good bacteria fall prey, too, and the full effects on the microbiome are unknown. One 2016 study suggested that antibiotic use in infancy could weaken the immune response later in life.

The Pathway to Anxiety