Self-Help

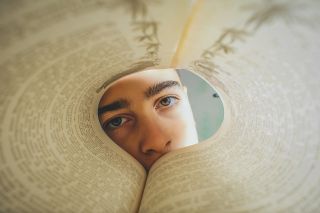

The Stories We Tell Ourselves Determine What We See

We all walk out of our childhoods with a story. Often they're wrong.

Posted October 18, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Each person has a story about themselves, others, and the world that determines what they see and expect.

- Some of the common negative stories are being unlovable, not capable, not appreciated, never getting a break.

- By being aware of their own story, someone can begin to change it by acting despite how they feel.

We all tell stories to others—scary or exciting events in our pasts, what we did or didn’t do over the weekend, what we’re struggling with right now. But there’s another story we tell ourselves, one that we often can barely articulate or even be fully aware of, a story about how we see ourselves, others, and the world. It’s a story created from our childhoods, and we add to it and refine it as we encounter life’s challenges. It becomes the lens through which we view the world that shapes our expectations, the script we learn to follow.

For some, these stories are positive—I’m a survivor; I can do it if I try. For others, they are more neutral: Life is filled with ups and downs, and you do your best.

But for still others, the stories are more pessimistic and handicapping. Their stories hold them back and make the world fearful or gray. But once you know your story, you can rewrite it.

Here are some of the most common stories that need to be rewritten:

I’m not lovable.

Unless you had others to help provide support and care, it’s hard not to walk out of your childhood with this story if you’ve been abused or neglected as a child. Because the story determines what you see and do, you attract others—partners, friends—who treat you a tad bit better than your parents but who abuse or neglect you nonetheless. If you do meet someone who treats you well—appreciates you, sees your strengths—you’re apt to run away, sabotage the relationship, or live in fear of them seeing who you really are and leaving. Because they don’t fit your story, it’s hard to believe what they say; you don’t trust them or feel like you can be the person you think they want.

I’m not capable.

You struggled with an undiagnosed learning disorder or had attention-deficit disorder, or you tried things but were horribly criticized. The resulting story is that you’re a loser, can’t do what others can do, and are not smart enough or skilled enough. If you carry this story, you not only see yourself as handicapped and one-down from everyone else, but you likely learned long ago to give up and not challenge yourself. You become a passive passenger in your own life.

I’m never appreciated; I don’t get the credit I deserve.

You quickly feel slighted; you’re sensitive to criticism; you compare yourself to others; life is unfair. The story here is rooted in feeling like the lost child in a family who never received enough attention and praise or from having critical parents who let you know that you never measured up. As a result, you’re competitive and jealous when a colleague gets a promotion at work, are constantly striving to get it right so you can get the attention and credit you deserve, or, like the unlovable folks, attract others who keep you feeling one-down.

Things rarely turn out well; I never get a break.

While those three stories are about you and relationships, this one is about you and the workings of the larger world—the original life sucks story. Here, you’ve learned to be pessimistic and cynical. You often feel like a victim, even of everyday events, and attract others who feel the same, consoling each other on how insensitive and harmful the world is. Depression is a familiar and strong undertow, but it’s easy to periodically blow up or become passive and stop trying.

The shoe always drops.

This story takes the previous one to a higher level of angst. This is less about cynicism and resignation and more about hypervigilance and ongoing anxiety. This is where big trauma kicks in, where you’re always looking around corners and looking ahead to worst-case scenarios, which are easily triggered by everyday life. Your story gives you some control by telling you that your best defense is expecting the unexpected, the worst. Here, folks develop a generalized anxiety disorder, rely on drugs or alcohol to lower stress, or have eating disorders or obsessive-compulsive disorders to control their reaction to their world.

Changing the story

The way out is being aware of the script and then changing it. Start by looking back on your life: If your life were a book, what would be its title? What recurring problems with others seem to dog you? What’s your everyday mood? These patterns give you clues to the story running your life.

If you sense the patterns but can’t clearly see them, get an outside perspective. Sometimes, this can be as easy as talking with your partner or best friend and asking them their sense of you and your life. They may be able to see a bigger picture that you can’t. But if they’re in the same small worldview as you, you may need to talk with an unbiased professional who can help you sort this out.

Once you’re aware, you have the opportunity for change. Much of our psychological lives are about upgrading our mental software from our pasts. Here, the challenge is acting despite your feelings, pushing back against the story that you’re not good enough or capable enough, or that the world is frightening and you need to be on guard.

Again, it helps to have support—friends, family, or professionals—but you can also take your own baby steps—not running away from the person who treats you well, not going down the rabbit hole of worst-case scenarios, pushing back rather than being passive when things don’t go your way. Start small—step up when you get the wrong change at Starbucks rather than accept what you get—but start.

We’re wired to see what we believe and find what we seek. By changing your story, you can begin to see life as it can be.

References

Taibbi, R. (2017). Doing Couple Therapy, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford.