Play

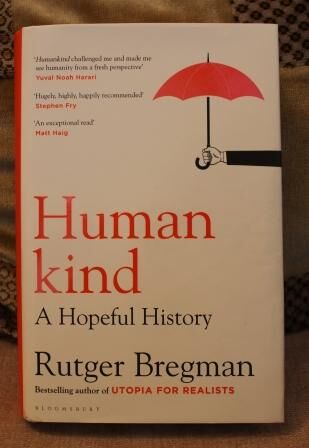

Humankind: The Case for a More Positive View of Humanity

Deep down, most people are pretty decent.

Posted February 25, 2021

After stealing a boat in June 1965, six teenage schoolboys were shipwrecked in a violent Pacific storm, arriving at a small, deserted island eight days later. They were rescued, by extraordinary luck, but not until September the following year. At the outset, they made a pact never to quarrel, separating to opposite ends of the island for a few hours to calm their aggression whenever friction arose. They created a food garden, hollowed out tree trunks to store rainwater, kept chickens in pens, made a kind of gymnasium and a badminton court, and also lit a fire, managing to keep it alight for more than a year. At the end, they were all in peak condition, including one boy’s perfectly healed broken leg.

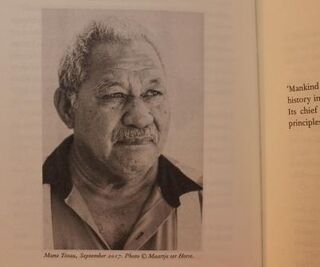

This heartening story runs counter to the grim fictional tale of William Golding’s twentieth-century classic book, The Lord of the Flies, which may have sold tens of millions of copies but turns out to be completely misleading... Fake news! The contrast between the two tales is made by Dutch author and journalist, Rutger Bregman, in his recent book, Humankind. To check out the Tongan boys' account, he even went to Australia to interview the sea captain who found them and one of those survivors living nearby. These two were firm friends still, 50 years later.

Bregman's central idea, backed by evidence and anecdotes, is that, "Most people, deep down, are pretty decent." Negative views, and opposing ideas like, "Most people think most other people can’t be trusted,” probably prevail, he says, because of an unhealthy addiction to "news" that is designed less to inform than to grab attention, hence its relentless focus on human misdeeds and suffering. People are not naturally combative. Taking his readers through an account of human evolution, he maintains that, “Although struggle and competition clearly factor… co-operation is much more critical.” Humans find ourselves in difficulties, though, because of a fatal flaw. As social animals, “We feel more affinity for people-like-us.” Forgetting that, ultimately, we are alike and powerfully connected, giving in to partisan, us-versus-them thinking explains why we make enemies and do bad things to them.

This does not always work to our advantage, though. For example, according to Bregman, bombing people, whether during the London blitz or in Vietnam, far from demoralising people, strengthens their resolve and encourages co-operation. There is also good evidence that in battle most soldiers never fire their guns. We are basically peace-loving. The inhabitants of the Bahamas were totally peaceful and entirely ignorant of weapons until Columbus showed up in 1492. Similarly, nonviolent people, totally abhorrent of bloodshed, were found on the Pacific Island of Ifalik after World War 2.

So... What went wrong? For Bregman, civilisation has many good points, but the problem started with the advent of settlements and private property, as a result of which, "The 1 per cent began oppressing the 99 per cent, and smooth talkers ascended from commanders to generals, and from chieftains to kings. The days of liberty, equality and fraternity were over.”

This excellent book goes on to debunk several other myths. The real story of Easter Island is, “Of a resourceful and resilient people… not a tale of impending doom, but a well-spring of hope.” Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment deliberately and fraudulently turned, “A scientific experiment into a staged production.” Milgram’s "shock machine" subjects were extensively coerced into using high voltage settings on purported "victims," to the point of lasting psychological trauma in several well-attested cases. The cries of Catherine Susan Genovese, attacked repeatedly at 3:15 a.m. in New York in 1964 were not ignored by 38 bystanders, and she did not die alone. Bregman concludes: “How out of whack our view of human nature often is; how deftly journalists push those buttons to sell sensational stories; and how it is precisely in emergencies that we can count on one another.”

Rather than unspeakable villains, as propaganda usually has it, Bregman says, "Our enemies are just like us.” Led by war criminals, for example, terrorists kill and die for each other, "Feeling part of something bigger, so that their lives finally hold meaning. Religion is an afterthought." To be clear, he adds, "This is no excuse for their crimes. It’s an explanation. Power is like a drug... It appears to work like an anaesthetic that makes you insensate to other people."

These are ideas worth reflecting on, as are those found in later chapters addressing questions like, "What if schools and businesses, cities and nations expect the best of people instead of presuming the worst?" To answer it, there is a description of a highly successful Dutch healthcare organisation run by someone who, "Sees his employees as intrinsically motivated professionals and experts on how their jobs ought to be done," and is therefore, "A manager who prefers not to manage." Later, about children, education and the need for play, Bregman writes, "Over the past decades, the intrinsic motivation of children has been systematically stifled," and, "Science has now supplied a mountain of evidence that unstructured, risky play is good for children's physical and mental wellbeing." Depression in adults, he adds, derives from, "A shortage of what makes life meaningful. A shortage of play."

Bregman is critical of contemporary "democracy," which ignores that people tend to be constructive and conscientious. Rather than being selfish, they tend to share readily. At the biological level, we are all kin, of the same kind, in a way that makes kind-ness natural and good. Using the example of South Africa's avoidance of bloodshed at the ending of the apartheid era, Bregman describes the essential part of the remedy as "contact": putting people together for long enough to get used to one another. Suspicion dies and bonding spontaneously occurs.

Covid-19 arriving during a period of global destabilisation, associated with multiple inter-related factors, including climate change and mass movements of both refugees and economic migrants, offers an unparalleled invitation and opportunity for people as individuals and collectively to reflect upon and revise their values, ambitions, plans and priorities, even if for the time being we cannot actually get together for discussion and mutual support. Written in a style that is relatively informal and personal, almost conversational, making it easy to read, there could hardly be a more appropriate, timely and helpful book as Humankind. "Bravo Bregman," I say.

Copyright Larry Culliford

Larry supports the World Wide Wave of Wisdom.