Play

The History and Psychology of Chess

Consider 7 life lessons we can take from the game of chess.

Updated May 16, 2024 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Chess began as chaturanga in the Gupta Golden Age of India.

- The game arrived in Europe in the tenth century, probably through Islamic Spain.

- As well as pure reason and pattern recognition, there is a great deal of psychology involved.

The Gupta emperor Kumaragupta (r. 414-455 CE) founded the Nalanda mahavira (monastic university), which is regarded as the world’s first residential university. Nalanda, in modern-day Bihar, attracted students from as far afield as Anatolia, Japan, and Indonesia, and played an important part in the development of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Though Buddhistic, it offered every subject, including the Vedas. It had ten temples, eight compounds, and a great library spread across three large buildings including the nine-storey Ratnodadhi (Sea of Jewels).

In around 640, the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang spent nearly two years at Nalanda, and described it thus:

The entire establishment is surrounded by a brick wall… One gate opens into the great college, from which are separated eight other halls standing in the middle. The richly adorned towers and the fairy-like turrets, like pointed hill-tops, are grouped together. The observatories are lost in the morning vapours and the upper rooms tower above the clouds.

At Nalanda, one of the Heads may have been the astronomer and mathematician Aryabhata (476-c. 550). In the Aryabhatiya, Aryabhata treats of geometric measurements, using 3.1416 for pi, which he realizes is an irrational number. He defines sine, cosine, versine, and inverse sine, and, in a single sutra (verse), supplies a table of sines. He also covers linear equations, quadratic and indeterminate equations, compound interest, and more.

One of the fields of study at Nalanda was medicine, or Ayurveda. Of the three principal Ayurvedic texts, the most interesting is the Sushruta Samhita, attributed to the physician Sushruta, who, like Aryabhata, flourished in the sixth century. Sushruta is known as the “Father of Plastic Surgery” for his description of rhinoplasty (nasal reconstruction) using cheek flaps. In the Sushruta Samhita, he details over 1,000 disease entities, 700 medicinal plants, 300 surgical procedures, and 121 surgical instruments.

The History of Chess

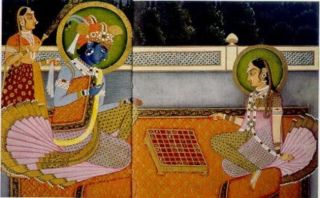

I like to think that, in their spare time, Sushruta and Aryabhata played chaturanga, the ancestor of chess, which, by the sixth century, had become widespread in Gupta India.

“Chaturanga” means “four divisions”, after the four divisions of an Indian army: elephantry, chariotry, cavalry, and infantry. Played on an uncheckered board, chaturanga had different pieces with different powers, with the objective being to capture the opponent’s raja (king) or reduce the opponent’s pieces to just the raja.

Over the centuries, the mantri (advisor) or senapati (general) morphed into our queen, the gaja (elephant) became the bishop, and the ratha (chariot) became the rook.

Remarkably, the raja, ratha, ashva (horse), and padati (foot soldier) moved the same way as their modern equivalents—the king, rook, knight, and pawn—although the padati did not have a double-step option on the first move.

In around 700, the Persians, who were quick to adopt the game, introduced the notion of warning that the raja (in Persian, the shah) was under attack to prevent an early or accidental end to a game. Later, the Persians added the rule that the shah could not be moved into check or left in check, meaning that he could no longer be captured but only made helpless (shah mat, checkmate).

Chess, in the form of the intermediary Shatranj, entered Europe in the tenth century, probably through Islamic Spain. Mediaeval players considered it nobler to win by checkmate, so that annihilation became only a half-win before altogether disappearing in around 1600.

7 Life Lessons From Chess

Chess is the aristocratic game par excellence, played by princes, politicians, and military commanders to hone their tactical skills, both on and off the battlefield. Although portrayed as a game of pure reason and intellect, there is, in fact, a tremendous amount of psychology involved.

I’ve been playing chess for almost as long as I can remember. Nowadays, I usually play online, in very short “blitz” games with a 60-second timer running on both sides.

Here are seven psychological insights garnered from those games:

- Your reputation precedes you. Your opponent will be intimidated by a rating that is much higher than their own. Similarly, if you win and they replay you, they will play with a half expectation of losing.

- First impressions count for a lot. Making a poor one can be useful. If you begin weakly, or slowly, your opponent will underestimate you and lower their guard.

- The best attack is the one that looks like a retreat. If your opponent is amid a frenzied attack, and thinks you’re on the back foot, they will not suspect or see that you are, in fact, manoeuvring for an attack of your own.

- Position, formation, or situation is more important than the total number or power of pieces. In other words, how you come at something is more important than what you've got. Sometimes, it's worth sacrificing a piece or two to manoeuvre into a stronger position.

- If in the habit of making legitimate moves, you may get away with making an undefended move, so long as you do not appear to hesitate before making it. In other words, if you bluff, do it boldly and seamlessly, on the back of a good reputation.

- It can help to suddenly change tack by refocusing on another part of the board and opening a new and unexpected field of action. Or, when a move is entirely expected, to make a completely different one, to confuse and destabilize your opponent.

- When badly losing, you can and should take big risks, like sacrificing important pieces, or making an undefended attack. Or you might try outrunning the clock.

These principles also apply to life outside of chess—whence the value of the game to princes and leaders.

Read more in Indian Mythology and Philosophy.