Cognition

Why Clever People Can Be Foolish and the Uneducated Clever

Mentalistic and mechanistic cognition can interfere to confuse the intelligent.

Posted July 6, 2014

Which is correct?:

- A. People drown by breathing in water.

- B. People drown by holding their breath under water.

Confronted with such a question, the vast majority of people would know that A was the correct answer. Now consider the following anecdote, seared on my memory for reasons that will quickly become apparent:

It was a conference at the London School of Economics in the early years of the new century on evolutionary psychology, chaired by the leading sociologist, Prof Lord Giddens, to which I had been invited along with the great and the good of the Darwinian and sociological worlds. In the course of an extempore comment, I pointed out that, although people indisputably have free will, the free will we have is limited to choosing from menus of options ultimately drawn up by our genes. I gave the example of suicide, making the obvious point that, although people can kill themselves by refusing food or drink, no one has ever committed suicide by holding their breath!

But at this point a well-known and very eminent professor of biology and neurobiology leapt to his feet and excitedly asked the audience “Whether Dr Badcock has ever heard of suicide by drowning?” A thunder of raucous laughter was immediately followed by hearty applause—and stunned silence on my part. The assembled intellectual elite of Darwinism and social science appeared to believe that people drown by holding their breath, and that my comment was completely laughable.

In other words, they had ticked B above! But how could this be possible? How could an elite audience of intellectuals with an average IQ well above 100, chaired by a member of the House of Lords and led by an influential professor, be so confused in its thinking?

After much painful rumination on this traumatic experience it was already apparent to me that the explanation must be that the audience was cognitively in mentalistic/moralistic mode, and could certainly not have been thinking rationally or objectively. But now a recent paper by Anthony I. Jack, Abigail J. Dawson, and Megan E. Norr may provide a much more general answer, based on their research into neural signatures associated with forms of dehumanization.

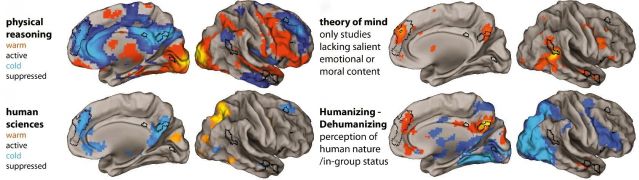

In a previous post, I highlighted the relevance of this research for the diametric model of the mind, and in this paper, the authors comment that “These findings suggest there may be an important distinction between the literal act of thinking about humans as biological mechanisms (scientific reasoning), and a process of social objectification.” Indeed, as I pointed out, it is one that can be imaged in the brain as illustrated below. As the images show and the earlier post explained, mentalistic thinking inhibits mechanistic areas, and vice versa.

I strongly suspect that my problem at the conference was that I was using scientific reasoning about a biological mechanism, but that the excitable professor was more interested in social objectification of my point as an instance of what he saw as dehumanizing biological reductionism—after all, I had uttered the scare-word gene! Hence his jumping to the conclusion that deaths by drowning contradicted my point, and—given that this was predominantly a gathering of the great and the good of social science—hence the audience’s ready complicity in ridiculing it. Indeed, looking at it another way, you could see it as an example of what in a previous post I called cloudy thinking.

But of course, if this is true—intelligent people thinking unintelligently because their brains were switched to mentalistic rather than to mechanistic mode—the diametric model implies that the reverse also ought to happen, and I believe it does.

A good example might be the finding that child vendors on the streets of Recife in Brazil were 98 per cent correct when doing sums involved in their trading activities on the street, but only achieved 37 per cent correct answers when asked to do similar calculations as abstract written test problems.

Effective trading is a mentalistic skill that demands much more than simply being able to do the relevant sums, as anyone who has ever been sold something they did not need will have learnt to their cost! Skillful selling demands an ability to vary or re-arrange buying options, exploit ambiguities, and generally to be flexible and inventive in presenting the advantages of the deal to the buyer while keeping track of the real costs to the seller. All of this demands high mentalistic intelligence, and it is perhaps not surprising that skill in arithmetic—in sharp contrast to abstract mathematics—is found more in women than in men.

But doing arithmetic in abstract written tests is quite different from doing it in the course of clinching a deal. Unlike handling money on the street, doing sums in a test is completely divorced from the social context, and is the kind of thing that adding machines or computers can do instantly—by contrast to doing dodgy deals, which they could not do at all! In short, the reason the street vendors did so comparatively poorly in the lab tests of their maths skills was that their arithmetic was being tested as an aspect of mechanistic intelligence, divorced from the social, mentalistic context in which they were used to applying it.

The street vendors, in other words, are the counter-example to the LSE intellectuals implied by the symmetry of the diametric model of the mind. If thinking in mentalistic mode can make highly intelligent people commit errors they would never make in an IQ test, then paper and pencil tests of mechanistic intelligence can make street vendors’ excellent mentalistic arithmetic skills seem poor by comparison!

The moral of this story is that you need to think carefully about which cognitive mode you are using when you try to solve a problem because, as I pointed out in the previous post, there is no one-size-fits-all-general-purpose mode of problem-solving—and certainly no single species of intelligence to go with it.

(With thanks to Anthony Jack. Illustration reproduced with kind permission from “More than a feeling: Counterintuitive effects of compassion on moral judgment,” by Anthony I. Jack, Philip Robbins, Jared P. Friedman & Chris D. Meyers in Advances in Experimental Philosophy of Mind, Continuum Press. Editor: Justin Sytsma, in press.)