Sex

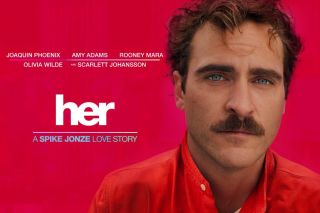

It’s All About Him: Reflecting on Spike Jonze’s "Her"

A Cautionary Tale for the Digital Age?

Posted December 27, 2013

Perhaps what is most disconcerting about Spike Jonze’s movie Her, an imperfect but thought-provoking futuristic look at love and technology, is that when you leave the theatre and go back into the real world —in my case, Third Avenue in Manhattan, where almost everyone had a cell phone in hand and where people were texting as they stood in line to exchange gifts or had a glass of wine with a friend— its premise doesn’t seem implausible. Granted, the Los Angeles Jonze presents us is without cars and has become more like a pedestrian mall than not, and there are subways too. Towering buildings with huge windows dominate the landscape, and interiors seemed stripped down to their essence. Personal style has vanished in favor of comfort, symbolized by the main character’s high-waisted, beltless trousers. There are no keyboards or wires in this future, just voice commands and hand gestures, which come to signify another kind of disconnection.

But the larger point is that the present—in fact, many of the topics I’ve explored in this blog—very much informs Jonze’s dystopian and somewhat depressing vision of love and relationship, played out between a dispirited, about-to-be-divorced Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix) and the object of his affection, an operating system named Samantha, voiced by Scarlett Johansson. What’s important to note is that the movie isn’t the rant of a Luddite but a thoughtful and often poignant look at how we live now may pan out in the future.

Theodore’s job at Beautifuhandwrittenletters.com tips us off to the point that in this future, people are no longer able to put their feelings into words on their own, and simply hire it out. It turns out that, for some of his clients at least, Theodore (writer # 612) has been “writing” what they feel for years. Of course, these letters aren’t “written” at all but spoken into a computer which then converts them into cursive. Given that forty-one states no longer require teaching cursive in schools, according The Cincinnati Enquirer, it doesn’t take much imagination to get to a time when the handwritten letter may be a nostalgic reminder of a pre-digital world.

Other present-day cultural tropes from the hook-up culture to how we get our news provide the fuel for Jonze’s vision. When Theodore allows as how he can’t prioritize between playing video games and Internet porn, it’s as if Michael Kimmel’s Guyland has become the script of the future. Similarly, it doesn’t seem much of a stretch to go from the kind of emotional disconnect Sherry Turkle has written about in Alone Together—becoming emotionally involved online, choosing a mate from a dating site, or breaking up via text— to falling in love with an operating system. In a world that already has “catfishing,” is Samantha the next logical step?

Now mind you, Samantha is no ordinary operating system. At the beginning at least, she’s not only inquisitive and sexy but hangs on Theodore’s every word, even as he warns her that he’s not ready to commit, and loves watching him sleep. She’s the perfect woman for a man without real- world emotional skills, the prototypical hook-up culture’s male, twenty years older and set in the future. She’s a personal assistant (deleting all those voicemails he’s been too disorganized to get rid of) and a super-Mom rolled into one, even choosing the best of his “letters” and sending them to a publisher who—in another nostalgic nod to the pre-digital world—puts them into book form. Yes, a book with pages and everything which actually arrives via snail mail, wrapped in paper and string!

Even the less subtle moments of black comedy seemed tethered in today. Except for Theodore’s ex-wife, no one else is bothered by the fact that he carries his “girlfriend” around in his pocket, and there’s a funny scene where a real couple, Theodore, and Samantha go on a double-date. The ease with which everyone accepts the relationship as “real” is reminiscent of how quickly the culture has accommodated itself to the “new normal” of living in the digital age, where seeing a couple eating dinner together while texting other people no longer seems strange or “friending” people you don’t know so you can get more attention or feel better about yourself is okay.

And yet, much in the movie suggests that Jonze is acutely aware that for all of the connection technology seems to offer, it has the potential to increase whatever existential loneliness people suffer. His hero is no prince among men, even if he does remind you of someone you might know. And for all that Theodore is praised by others for his sensitivity, he is also profoundly walled-off. He’s blown the one real relationship he had, that with his wife —revealed in flashbacks —but he worries most that he’s already felt all he’s going to feel. Technology allows Theodore to connect without the messiness, the bother, of human interaction. He’s gotten so used to phone sex that when he goes on a blind date, he’s visibly disturbed by the date’s instruction on how to kiss and then balks when she asks whether he’s just going to use her for sex. It doesn’t seem to bother him that Samantha is literally disembodied; ironically, in her quest to become human, it’s she who is troubled. Similarly, it’s no accident that Theodore’s friend Amy, played by Amy Adams, finally ends her marriage because of her husband’s inability to deal with her, and her mess. (He insists she leave her shoes by the door.) Theodore and Amy, long-time friends, don’t turn to each other in crisis but, instead, to their respective operating systems.

It’s hard not to see Her as a cautionary tale, reminding us that maybe all that the digital age has ushered in may not be as innocent or innocuous as it seems, despite our collective willingness to go along for the ride. In the end, it may have you looking at how plugged in you really are.

Copyright © Peg Streep 2013

VISIT ME ON FACEBOOK: www.Facebook.com/PegStreepAuthor

READ MY NEW BOOK: Mastering the Art of Quitting: Why It Matters in Life, Love, and Work