Well, shit. Now that I blowed his face off... Marco ain't worth a pesso! ~Maj. Marquis Warren, The Hateful Eight

“A Mexican Standoff is a confrontation among two or more parties in which no participant can proceed or retreat without being exposed to danger,” so Wikipedia, and it can be seen as “a poor man’s mutually assured destruction,” so the Urban Dictionary. The canonical image is of two or more gunmen pointing their pistols at each other. Popular movies and TV shows are full of MS. In the world of entertainment, the MS is often resolved by one party making credible threats beyond the exchange of bullets (I planted a bomb in your house, which will go off and kill your family as soon I die), or, and more intriguingly, by promises of non-violence (I’ll put my gun down if you put yours down), or even more intriguingly by pay-it-forward trust (I will put my gun down, but I expect you to put down yours as well). Sometimes it ends well, other times it does not. Just as in real life. In quotidian MS, two (or more) parties have boxed one another into corners of hurt feelings, bruised egos, and tarnished reputations. No one wants to give in, but if no one does, the outcome is a sour one for all. All would prefer de-escalation if it could be achieved.

To understand the challenges to strategy, let us consider three scenarios of the gunman MS. They all have in common the idea that if shots are fired, they will be deadly, and that once dead, it does not matter if the other is dead or alive.

Scenario 1: Life and death only

Each gunman has a choice between Shooting [S] and Desisting [D]. If one chooses S, the payoff is life [1] if the other chooses D, and it is death [0] if the other chooses S. If one chooses D, it’s the same: [1] if the other D and [0] if the other S. In other words, if you shoot, they other is indifferent between shooting and desisting. He will be dead either way. If you desist, the other is also indifferent between shooting and desisting. He will live either way. This result is a game-theoretic oddity. There is no mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium. The other is indifferent between shooting and desisting no matter what you do, or with what probability you do it. If both players were to care only about their own life (good) and death (bad), they should both desist. They can come to this conclusion individually and then discover that their dilemma was spurious. Shake hands and go back to the families.

It can’t be this easy, right? Scenario 1 must be missing some psychological ingredient that makes the MS a nasty dilemma. Let’s add greed to the mix.

Scenario 2: Life, death, and spite

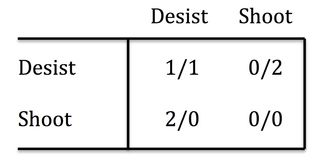

Each gunman would love it if he could shoot [S] a desister [D] and reap life and glory [2]. Mutual life is still good [1], and being shot [0] is still bad. Desistence is bad because it provides the other with an incentive to shoot. If you shoot, however, the other is indifferent between desisting and shooting because he will be dead either way. Shooting weakly dominates desisting; you either do better [if the other desists] or equally bad [if the other shoots]. So we expect both to shoot. Again, there is no mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium. The expected value of shooting is twice the expected value of desisting regardless of what the other does, or with what probability. Now this is a nasty standoff.

Scenario 3: Life, death, and guilt

Cinematic gunmen are not known for their conscience. Suppose they had one and would prefer mutual desistence [2] over living as a killer [1], while death, as in the other two scenarios, is unwelcome regardless of whether it is solitary or shared [0]. All it takes here is for one man to desist, and the other will realize that he is better off desisting too. The mixed-Nash is not defined, as above. So this scenario is not much of a challenge.

Degenerate Chicken

Since scenario 2 is the gloomiest, let’s take a closer look. The payoff matrix on the left shows what is at stake. It also shows the similarity of the MS to two well-known games. In the prisoner’s dilemma, it is worse to be shot while the other lives than to be shot while being able to return the favor. In the game of chicken, it is worse to be mutually shot than it is to be shot alone. In the MS, being shot confers the maximum disutility (death) regardless of what happens to the other. Remember: the dead do not care. Their conscience and their egos are extinguished.

Think of the MS as a degenerate game of chicken (or prisoner’s dilemma). Although game theory regards shooting the rational choice (because it weakly dominates desisting), both gunmen are united in their preference for mutual life. But they can’t have it because each would have an incentive to defect and shoot the other.

Mutual desistence is more ”efficient” than mutual shooting. This inequality makes the MS a non-zero-sum game. But how can this efficiency be achieved if a rational gunman shoots? Several remedies have been proposed to overcome the destructive dictates of game theory. Social preferences, trust, social projection, and team reasoning are among these (e.g., Krueger, DiDonato, & Freestone, 2012, and the commentaries). These remedies tend to work when the two players have to act simultaneously. This condition is not satisfied in the MS. As soon as one man lowers his gun, the other shoots. Nor can they institute simultaneity by agreeing that they will both make their choice (by either shooting or by throwing away the gun) when the clock strikes 12. If they tried this, they would only create a meta-game. Row gunman can shoot Column gunman as soon as Column signals that he will wait for the clock to strike.

This is frustrating. When there is a non-zero-sum game in which mutual cooperation pays more than mutual defection, while rationality demands defection, we want to find a way to cooperate without fear of being exploited. Movie-script writers have to find ways to undo the MS – at least some of the time – because if they did not, their characters would die off too quickly. Their most common ploy, as far as I can tell, is to bring a third gunman to the scene. Gunman 3 supports Row by pointing his gun at the back of Column’s head or vice versâ. Usually, what happens next is that Column lowers his gun.

This is astonishing. Why would Column lower his gun? Before the appearance of gunman 3, Column rationally expected mutual death with Row, and he expected to be shot if he unilaterally desisted. To desist now, with 2 guns pointed at him, should not affect this calculation; indeed, Column should now be even more convinced that he will be shot if he desists. Arguably, the MS might be defused if gunman 3 pointed a gun each at Row and Column, assuring both that they cannot achieve the life + glory payoff [2], but we rarely see that on the screen.

Positive sum games

This brief excursion in the Tarantino world of guns and threats illustrates the potential destructiveness of rational behavior is strategic dilemmas. Once the guns are drawn, it’s too late for the two players to find a resolution. Some third force needs to intervene, and there is no guarantee that such a force will awaken in time. How then can the positive sum of mutual cooperation be attained? It seems to me that foresight can help. A foresighted player anticipates when a situation might devolve into a MS, and then avoid this situation altogether. If both players are foresighted in this way, they both win (“What if there was a war, and no one showed up?”). If only one of them yields by giving the other what he wants, both live, although one is richer than the other. In short, the foresighted player can redefine the Mexican Standoff as a game of chicken. In chicken, yielding comes at a material or reputational cost, but the outcome is better than mutual destruction. What is more, if both players understand that they are playing chicken and not standoff, the various strategies noted above (trust, projection etc.) can help bring about the collective good of mutual cooperation.

A few post-traumatic notes:

[1] When sitting down to express my blogger's gene, I had a choice between

[A] writing an essay on how to talk to women, or

[B] writing an essay on mutually assured destruction among men.

I chose the easier topic.

[2] I don't think the Mexicans should be burdened with the eponymy of this standoff. It looks rather Wild-West Gringo-ish.

[3] Google scholar offers next to nothing on this interesting dilemma. I found a slightly dated sociology paper that mentions the Mexican Standoff as a game-theoretic scenario but offers no references. See if you have better luck.

[4] The two clay gods are Mexican indeed, and I am their proud owner. After a little search on the net I discovered that they are Azt- and not Olmec.

[5] A reader asked if there are Mexican Standoffs outside of Hollywood. I advised him to find MS in his own life, and count his blessings if he can't. At the macro-level, conflicts that have come to be labeled 'intractable' tend to be of the MS variety. Consider Israel/Palestine.

Krueger, J. I., DiDonato, T. E., & Freestone, D. (2012). Social projection can solve social dilemmas. Psychological Inquiry, 23, 1-27.