Neuroscience

Groping the Body Politic

The grounding of meaning in bodily experience could have political consequences.

Posted November 1, 2016

What is meaning? How much is linguistic meaning grounded in experience? Does it matter for the extraction of word meaning whether people have actual, physical experience with the events that words represent? Cognitive scientists, linguists, and philosophers have puzzled over questions like these.

Politicians might not think much about how much linguistic meaning is grounded in experience. But a person who may want to be very concerned about questions like these is a few days away from the biggest face-off of his life – U.S. Republican Presidential candidate Donald Trump.

Trump has minimized the importance of specific instances of language use. During the 2nd U.S. Presidential Debate on October 9, 2016, after Clinton outlined some plans for how she would address the nation’s problems, Trump looked at the camera and said “It’s just words, folks. It’s just words.”

And, when challenged to explain recorded remarks from 2005 about his use of his celebrity status to grope women -- “Grab them by the p---y. You can do anything.” -- Trump repeatedly replaced any sort of meaningful explanation with the gloss-over: That’s just “locker room talk”[1].

Despite Trump's minimalizations, words matter. This may seem obvious, particularly for the 2016 Election. The electorate has hooked onto news coverage of Clinton’s electronic handling of words (emails!), and Trump’s words about women (Tic Tacs!) – the polls have shifted in response.

Swings in the polls in response to these “hot topics” demonstrate something researchers in neuroscience and cognitive linguistics have long stressed – people largely make sense of events in the world in a similar way.

For example, people show little variability in where in time they naturally segment events into smaller mini-events (e.g., making a bed, Zacks, Tversky & Iyer, 2001). And, people understand the causes of some kinds of events, such as various kinds of judgments, in similar ways. For a simple illustration, when asked to choose between “he” or “she” to continue sentences conveying judgments like “Amy praised Matt because…” about 80% of the time, people select the pronoun referring the sentence object (here, “he”, not “she”); Bott & Solstad, 2014; Niemi, Hartshorne, Gerstenberg & Young, 2016). Moreover, people use many overlapping parts of the brain to represent events regardless of whether the events are experienced in the flesh, viewed on the television screen, or described with words (Barsalou, 2008; Jackendoff, 2002; Johnson, 1990; Pulvermüller, 2005).

These findings point to a few broad things about human cognition. We understand some things about events by operating on mental simulations, and such processes occur very rapidly and typically without our awareness. They also suggest that we all viewed pretty much the same debate, heard the same words…maybe even saw similar Trump and Clinton imagery in our heads, and extracted similar meanings from it. To these meanings, presumably, we then applied our committed “Republican” or “Democrat” lenses and opined accordingly.

On the other hand, few people missed the FiveThirtyEight maps showing "What 2016 would look like if just women voted" -- a sea of royal blue in favor of Hillary Clinton, which contrasted starkly with "What 2016 would look like if just men voted" -- a bright red stop sign in favor of Trump.

These dramatic maps show us that there is a gendered aspect to the election. They also remind us of the importance of consideration of individual differences when thinking about human cognition. Word meaning may be largely “encoded” or “locked in”, but it can also vary based on whether one has experienced the events that words represent. Experiences, of course, hinge on things like whether one belongs to a particular social category, e.g., woman, man.

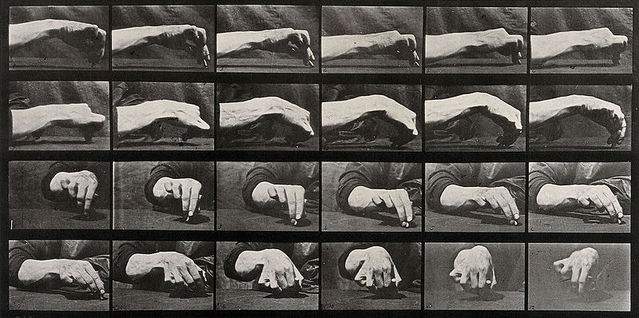

Researchers have found that actual, physical experience with particular kinds of actions is associated with different patterns of brain activity for words related to those actions (i.e., ice hockey experts show different neural response patterns to ice hockey words compared to non-experts; Lyons et al., 2010). It’s not unreasonable to speculate that the phrase “Grab them by the p---y” may actually be represented differently in the brains of men and women. For example, due to the facts of anatomy, the phrase might differentially activate brain regions associated with manual grasping, genital sensory processing, and aversive affect in men compared to women[2].

When Trump said these words, they may have been felt by women in a way that Trump simply cannot readily understand. The minimizing statement, “It’s just words, folks”, uttered in the second debate, may have served to further discredit their experiences.

What can be done when people simply can’t see eye to eye – in part because they've had very different prior histories?

One possible solution may lie in attempts to step into the other person’s shoes. By imagining what it would be like to live in a body like someone else's, we may be better able to imagine the effects our words have on them.

References:

Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 617–645.

Bott, O., & Solstad, T. (2014). From verbs to discourse: A novel account of implicit causality. In Psycholinguistic Approaches to Meaning and Understanding across languages (Studies in Theoretical Psycholinguistics). In B. Hemforth, B. Mertins, & C. Fabricius-Hansen (Eds.), (p. 213-251). Cham: Springer.

Jackendoff, R. (1985). Semantics and cognition. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Johnson, M. (1990). The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. University of Chicago Press.

Lyons, I. M., Mattarella-Micke, A., Cieslak, M., Nusbaum, H. C., Small, S. L., Beilock, S. L. (2010). The role of personal experience in the neural processing of action-related language. Brain & Language, 112, 214-222.

Pulvermüller, F. (2005) Brain mechanisms linking language and action. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6, 576-582.

Zacks, J. M., Tversky, B., & Iyer, G. (2001). Perceiving, remembering, and communicating structure in events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130, 29–58.

Note:

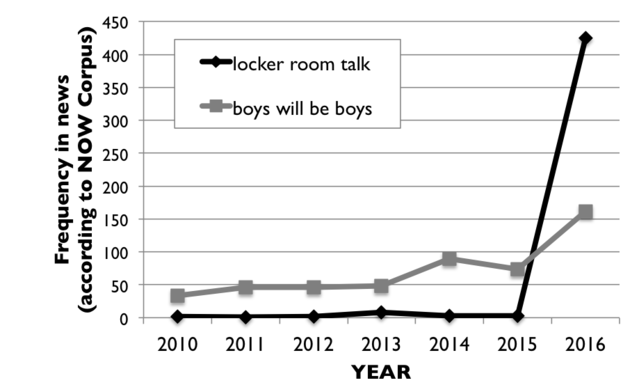

[1] "Locker room talk", incidentally, is treated as a familiar cliché, but was used in the news only 19 out of 444 total recorded times [According to a search of the NOW corpus (News on the Web) on 11/1/2016, which contains "3.5 billion words of data from web-based newspapers and magazines from 2010 to the present time"] between 2010-2015, with a spike of 425 times in 2016 -- nearly all of which were in October 2016. By comparison, the phrase "boys will be boys" (total frequency 2010-2016, n=499) was used more equivalently each year between 2010-2015 with a bump this year, see graphed results from NOW corpus analyses below:

[2] History of sexual trauma would also perhaps factor into neural response patterns.