Gratitude

How Does Gratitude Enhance Trust?

New research on the influence of gratitude.

Posted February 7, 2017

For those without subscriptions to self-improvement fanzines such as Live Happy, Success, YES! Magazine, Exceptional Magazine, Self Magazine, New You, and Self Obsession, you still have my respect.

Unfortunately, this means that you might be less versed in the massive scientific literature that shows being grateful is good. A literature that has been watered down into a single mantra: Gratitude can make you a better you!

You know there is a reason to be grateful when you wake up in the morning. You know there is someone you do not fully appreciate. Scientists have emerged from every corner of the globe to bludgeon you with reasons why it is time to start a practice of gratitude now.

Want a 54-inch chest? Be grateful. (He doesn't quite say the word but you can feel the sentiment).

Want to survive a horror movie despite being cast as a token minority? Be grateful.

What Is Gratitude?

Gratitude is the mindful recognition of benefits or gifts received that are attributed to the kindness of other people. Although traditionally seen as integral in philosophy and theology, gratitude research was almost completely neglected until the emergence of a wave of research in the first few years of the 21st Century. This contemporary research achieved notable successes in trait and interventional research.

Feeling grateful has been associated with less frequent negative emotions and thoughts, more frequent positive emotions and thoughts, greater meaning in life, more positive coping, greater appreciation of life, and even better sleep and exercise (Note: This is weird, if you ask me why I will be blunt—I have no $#@ clue) (e.g., Lambert, Graham, Fincham, and Stillman, 2009; McCullough, Emmons, and Tsang, 2002; Wood, Maltby, Stewart, and Joseph, 2008; Wood, Joseph, and Linley, 2007; Wood, Joseph, Lloyd, and Atkins, 2009). Much of these links were shown to be unique, occurring independently of other personality traits and across self and informant ratings (Breen, Kashdan, Lenser, and Fincham, 2010; Wood, Joseph, & Maltby, 2008, 2009). Gratitude was also shown to be clinically relevant, for example:

(a) Predicting better psychological adjustment in combat veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (Kashdan, Uswatte, and Julian, 2006) and adults managing major life transitions (Wood, Maltby, Gillett, Linley, and Joseph, 2008).

(b) Leading to fewer, less intense aggressive reactions following provocation (DeWall, Lambert, Pond, Kashdan, and Fincham, 2012).

(c) Lower suicidal risk (Li, Zhang, Li, Li, and Ye, 2012).

This wave of research was seminal in showing that gratitude is integral to well-being, relevant to clinical issues, and can be increased therapeutically. However, there are limitations to this pioneering work that need to be addressed.

A Contextual Lens

It is time to view gratitude as less of a panacea and more of a mechanism that facilitates healthy outcomes. From this vantage point, it is necessary to test potential causal links between gratitude to psychological and social well-being, and the efficacy of gratitude therapies on real-world changes in social behavior. My colleagues and I recently conducted a study to add to this literature. We wanted to know whether participation in a gratitude intervention would alter behavior and physiological reactions during a social interaction with a stranger.

A sense of psychological safety is a precursor to forming satisfying, meaningful relationships. A sense of psychological safety in organizations is a precursor to doing exceptional, innovative work.

Trust.

During times of uncertainty, when an important goal exists, are you willing to rely on another person?

We wanted to know whether gratitude facilitates trust during an actual social interaction with a stranger when financial benefits are at risk. Here is what we did:

First, half of the study participants completed an online gratitude intervention (reflecting on up to five things in their life that made them grateful over the past few days) or an active placebo (reflecting on up to five things they did over the past few days).

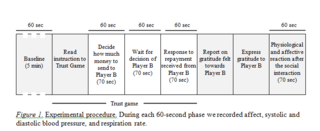

Second, a few days later they arrived at the laboratory for the trust game. The game began with a baseline assessment where we collected continuous data on their subjective feelings (with a rating dial that they could turn at any moment) and cardiovascular and respiratory activity. After learning about the rules of the game, they decided on how much money to send the other player—knowing that if the other player reciprocated, they would double their money. But we didn't want them to get off easily, so we had them wait, alone, wondering what the other player would do.

Essentially, the interaction was broken up into eight parts to capture the anticipation, the decision of whether to trust, wondering what the other person would do in return, how to respond to their gesture (of reciprocation or not), and a post-mortem about how the entire social interaction unfolded.

By deconstructing a social opportunity to trust a stranger we were able to explore the exact moments when people exposed to a gratitude intervention differed from their peers. Here is what we found:

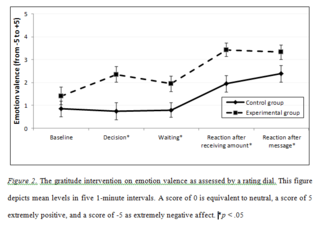

Yes, we found that adults in the gratitude intervention experienced more positive emotions in a social interaction, where trusting a stranger was essential to earning money. But we failed to find group differences at baseline. Think about what this means for a moment. Being in an intervention to become grateful has no impact on anticipating a social interaction with greater positivity. You are no different than anyone else. This also speaks to the futility of research which tries to show that gratitude is correlated with questionnaires, interviews, neurobiological activity, and other global indices of positivity. Researchers are asking the wrong question. Instead of asking does gratitude training make people experience positive emotions more intensely or frequently, ask under what situations is gratitude training helpful? We found an important situation where gratitude training does not offer benefits beyond a placebo - at rest; while waiting for an interaction to begin. The benefits did not emerge until meaningful decisions and actions occurred.

This is the first study to explore the exact contextual conditions that influence emotions experienced, subjectively and physiologically. Interestingly, we found that adults in the gratitude intervention entrusted more money to their game partners—evidence that gratitude does lead to more trust. Those in the placebo condition sent 52.1% of the money at their disposal whereas those in the gratitude intervention sent 69.6%, evidence of a meaningful behavioral boost in trust.

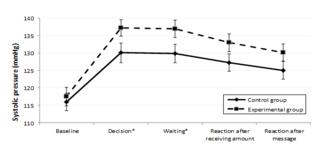

But there was a physiological cost to being grateful and trusting. There was a heightened level of uncertainty that was particularly pronounced during the decision of whether to trust a stranger and the seemingly infinite waiting period to determine whether that act of faith was warranted or foolish.

Context matters.

Something that gets lost when our questions are too simplistic: Does gratitude predict greater well-being? Is it healthy to be grateful? Are grateful people friendlier, trusting, and trustworthy people?

Gratitude appears to be linked to trust. But the details matter. People in a gratitude intervention endorsed the greatest positive emotions when deciding to trust a stranger but they also experienced heightened physiological arousal - tension that remained at a high level until after the interaction was over.

Be anti-parsimonious.

Let's nail down the nuances of personality strengths such as gratitude, interventions to enhance these strengths, and how they influence the anticipation, experience, and aftermath of decision-making in the real-world. Only then will we truly learn about how humans behave and where to intervene.