Stress

What Happens When Your Stress Exceeds Your Window of Tolerance

5 ways to decrease arousal.

Updated January 14, 2024 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- We all have a “window of tolerance,” which is an optimal arousal zone.

- Stress and other difficult emotions can bring us to the edge of that window.

- Being mindful of our "inner landscape" and practicing certain exercises can return us to a state of calm.

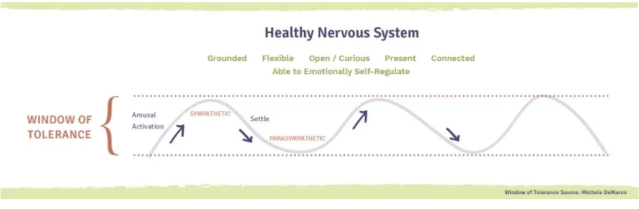

According to psychiatrist Dan Siegel (2012), we each have a “window of tolerance.” Siegel coined the term to describe normal brain/body reactions, especially following adversity. The idea is that human beings have an optimal arousal zone that allows emotions to ebb and flow, which, in turn, enables a person to function most effectively and manage the everyday demands of life without difficulty. Thanks to the deleterious events of the last few years, for many people that ebb and flow has been dammed.

A recent poll (Panchal et al., 2023) by the Kaiser Family Foundation showed that concerns about mental health remain elevated three years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 90 percent of U.S. adults believing that the country is facing a mental health crisis; moreover, half of young adults and one-third of all adults reported having felt persistent anxiety in the past year. Another study (Walsh, 2022) found that social media use among college students led to a 7 percent increase in severe depression and 20 percent in anxiety disorders. A study by Mental Health America (2022) found that nearly 5 percent of adults report having serious suicidal thoughts, totaling over 12.1 million individuals.

What the data makes clear is that if you’re worried, scared, anxious, depressed, irritable, confused, frustrated, grieving, exhausted, struggling to sleep, or just on edge (sigh), you’re not alone. As Joshua Gordon, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, said to the Washington Post, “Given the circumstances, feeling anxious is part of a normal response to what’s going on.”

Understanding Your Window of Tolerance

When a person is within their window of tolerance, they are, generally, able to think rationally, reflect and discern, function well, and make decisions without feeling overwhelmed. If they experience distress that brings them close to the edge of their “window,” they are typically able to leverage strategies to keep from leaping out. But with the prolonged and unprecedented levels of stress today, the effect can feel more like being pushed out of that window.

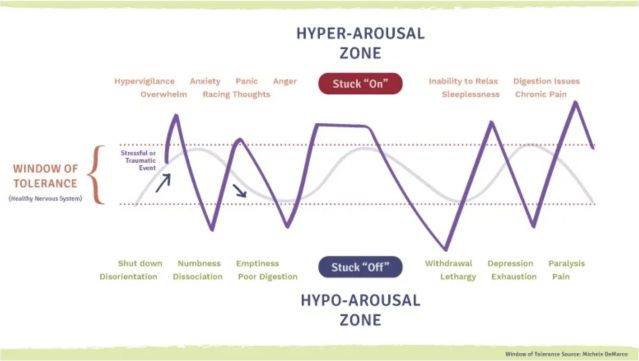

For people who have experienced trauma or chronic adversity early in life, this feeling is like being catapulted out of that window. This is because traumatic experiences imprint themselves on our physiology: a person’s senses become heightened, which sends them into a “perma-hyper-alert” state; and experiences and reactions intensify, so that everything seems more severe or even doomsday. Both responses make a person’s window drastically smaller and make finding strategies for coping that much harder.

While this experience doesn’t feel good, it is the result of our natural defense system triggering a survival-based response. The body processes perceived threats through the autonomic nervous system, an involuntary and reflexive “behind-the-scenes” mechanism that helps to keep us alive.

The nervous system has two major branches: the sympathetic nervous system, which mobilizes the body’s internal resources to act if there’s a threat; and the parasympathetic nervous system, often called the “rest and digest,” “feed and breed,” or “tend and befriend” system, because it dampens the acute sympathetic responses and keeps the body in a restorative and resting state.

When operating in our window of tolerance, these two branches play a happy game of “tag, you’re it”—working together to manage the body’s responses depending on the situation. For instance, if you’re running late for a meeting, the sympathetic nervous system may kick into gear during moments of rushing or worrying about the consequences of being late. Once you get to the meeting and settle in, the parasympathetic nervous system takes over and re-regulates the body back to calm and normal functioning.

But during extreme times of stress, one or both branches can get out of whack. What results are periods of either hyper- or hypoarousal.

Hyperarousal, commonly referred to as the fight/flight response, is associated with the sympathetic nervous system and is a system “stuck on.” In this state, a person can become hypervigilant, anxious, panicky, angry, overwhelmed, or consumed by racing thoughts. It can be hard to relax or sleep. They might also experience chronic pain or digestion issues—what we often call a “nervous stomach.”

Hypoarousal, commonly referred to as the freeze response, is associated with the parasympathetic nervous system and is a system “shut off.” It causes people to shut down and withdraw or to feel numb, empty, exhausted, depressed, and stuck. They may have little energy or motivation. They may also become disoriented or dissociate.

In either state, it can become difficult to process thoughts and other stimuli as we otherwise would. This is because the prefrontal cortex area of the brain—where rational, higher-order cognitive functioning occurs—effectively shuts down.

The prefrontal cortex is essentially a control center that corrals our baser emotions and impulses. It’s the “super-sensitive” area of the brain that evolved most recently—so much so that even short-term anxieties and everyday worries will cause neurochemical changes that can immediately weaken network connections. When this happens, the nervous system becomes dysregulated, and we move outside our window of tolerance.

If you’ve experienced this kind of dysregulation, or observed it in someone else, perhaps you’ll recognize how your (or their) response to things—like sudden noises, a remark, dropping something as simple as a pen—become more rigid, intense, or chaotic and harder to endure. Overreacting to harmless triggers or false alarms is a hallmark of being out of your window of tolerance.

Expanding Your Window of Tolerance

“Get over it” (“it” being distressing emotions that erupt when you’re outside your window) is a self-talk technique often employed to combat the upsetting feeling. “Think happy thoughts,” “Don’t be stressed,” and “Be calm” are a few others.

The problem is that the nervous system doesn’t easily understand this rational, higher-order cognitive functioning language. It prefers “somatic speak”—meaning tuning into the body for messages to help it shift an out-of-whack arousal level back to normal functioning. Because everyone’s window of tolerance is different, the key is to determine what works for you specifically, and when.

What follows are some practices to help when you find yourself outside of your window and in either a hyper- or hypoarousal state.

To decrease arousal (for hyperarousal)

- Diaphragmic or “belly” breathing. Diaphragmatic breathing means that when you inhale, your belly expands outward. When you exhale, your belly caves in. The more your belly moves, the deeper you’re breathing—which is what you want.

- The diver’s reflex/cold exposure. Hyperarousal makes you feel “hot under the collar.” The “diver’s reflex”—the body’s physiological response to acute submersion in cold water—can help ease that feeling. This post (DeMarco, 2023) provides more information.

- Grounding techniques. Grounding (or “earthing”) is a way to focus on what is happening to you physically, whether in your body or your surroundings. It’s a technique that breaks the cycle of hyperarousal by bringing you into the present, and out of fixating on the past or future.

- Container/“self hug.” Don’t let the name fool you. This is an effective calm-down exercise. It was created by trauma researcher Peter Levine (2024).

- Unexpected ways. Try drinking from a straw, or humming, singing, chanting, and gargling. Laughter also works, as does jumping on a trampoline. Use a weighted blanket at night for sleeping. (Research by Mullen et al., 2008, shows that deep pressure stimulation can help reduce autonomic arousal.) Try prayer or meditation.

To increase arousal (for hypoarousal)

- Sensory stimulation. Anything that arouses your senses can be helpful for getting out of that low-feeling “freeze.”

- The squeeze ball. Paced resistance, such as squeezing and releasing a tennis ball or small yoga ball can help to bring energy into your body back slowly and safely.

- Grain balloon. Multisensory attentional activity can help to reignite your nervous system when it’s “stuck off.” Get a small balloon and fill it with some kind of crunchy grain. Hold the balloon with both hands, and slowly roll it forward, squeezing and kneading with each turn. Pay attention not only to how it feels, but also listen to the crunching sound.

- Get into your thinking brain. Activating your mental processes can help to bring you back into your window of tolerance. Look around the room and name all the colors you see. Count the windows, chairs, or books on a shelf that surround you. Hold and describe an object, speaking out loud.

- Unexpected ways. Try finger painting, playing with Play-Doh or clay, and blowing through a straw.

We all have moments that push us beyond our window of tolerance. Understanding the personal systems, tendencies, and history that cause this to happen can go a long way toward helping us deal with life’s stressors.

It is important to remember that our window of tolerance can change from day to day, or even moment to moment; for instance, feeling tired, hungry, or sick often narrows our window. Also, bear in mind that stressful situations affect people differently, so don’t beat yourself up comparing yourself.

What matters is understanding the mechanisms of your specific window of tolerance, and this requires paying close attention to the patterns of your responses and to what’s going on inside your body when they occur. My new book Holding Onto Air: The Art and Science of Building a Resilient Spirit offers practical advice for managing your window of tolerance.

Facebook image: Rawpixel.com/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: SYC PROD/Shutterstock

References

Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R. E., Mavall, E. E. (2021). “Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: “A global survey,” The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(12). https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3

Levine, P. (2024). “Two simple techniques that can help trauma patients feel safe.” National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine. https://www.nicabm.com/trauma-two-simple-techniques-that-can-help-trauma-patients-feel-safe/

Mullen, B., Champagne, T. T., Krishnamurty, S., Dickson, D., & Gao, R. (2008). Exploring the safety and therapeutic effects of deep pressure stimulation using a weighted blanket. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health. 24, 65-89. DOI:10.1300/J004v24n01_05

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. W. W. Norton & Company.

Panchal, N., Saunders, H., Rudowitz, R., and Cox, C. (2023) “The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use,” Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/

Reinert, M, Fritze, D. & Nguyen, T. (October 2022). “The State of Mental Health in America 2023” Mental Health America, Alexandria VA. https://mhanational.org/sites/default/files/2023-State-of-Mental-Health-in-America-Report.pdf

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Walsh, D. (2022) “Study: Social media use linked to decline in mental health,” MIT Management Sloan School. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/study-social-media-use-linked-to-decline-mental-health

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2013). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Siegel, D. J. (2020). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.