Play

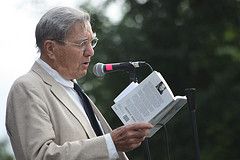

Galway Kinnell and the Eating of Oatmeal

In flights of fancy, poets reveal their imaginary companions and worldplay.

Posted December 9, 2014

Many consider the poet Galway Kinnell, who died last October at age 87, to be one of those rare and serious talents who come along only once or twice in a generation. And yet Kinnell was not above a certain down-to-earth whimsy tied, at least in part, to the playful invention of imagined people and places.

Take Oatmeal as a case in point. If you listen to or watch Kinnell read this poem, you’ll hear lots of laughter from his audience. You’ll also hear him call upon the powers of play as he seeks to enliven a breakfast of oatmeal with a little fantasy. It is better for one’s sanity not eat the “glutinous,” “gluey,” “slime” alone and so, he explains,

"That is why I often think up an imaginary companion to have breakfast with."

Kinnell invites John Keats to dine, only to discover that Keats had similarly invited Edmund Spenser and John Milton to chat over a bowl of oatmeal. As many readers will recognize, Kinnell has much to say in this poem about the writing of poetry. But he is also, quite literally, channeling a wider history of imaginary world invention that often begins in childhood—but does not necessarily end there.

In his memoirs, for instance, fellow poet and writer Robert Louis Stevenson lovingly described his boyhood flights of oatmeal fancy. “When my cousin and I took our porridge of a morning at breakfast, we had a device to enliven the course of the meal,” he wrote. The two envisioned countries buried under the snow of sugar or flooded with the waters of milk. Indeed, from breakfast to dinner, sunrise to sunset, youth to maturity, Stevenson immersed himself in play with imaginary worlds and the imaginary people in them.

Perhaps Kinnell knew of Stevenson’s worldplay. But whether he did or not hardly matters, for he had his own to draw upon. And it was our privilege to hear about it when he participated in Michele’s Worldplay Project.

Among many other honors and recognitions, Kinnell received a MacArthur Prize Fellowship in 1984. As a member of that august group he responded to Michele’s query concerning the invention of imaginary worlds and granted her a phone interview. As a participant in her Worldplay Project, they talked at length about his childhood play in imagined places:

GK: I had three older siblings, a brother and two sisters… The oldest one played….paper dolls, she didn't deign to go with us when the three of us descended into the cellar to play Little Men. We did it quite a number of times. And in the course of doing it, we built a little village and had houses, rooms and furniture and everything.

They actually had embodiments, because there was such a thing then called toy soldiers made of cast iron. After a while they disappeared from the shelves. I think they must have been made in Japan or something, because when the war between the United States and Japan developed these things seemed to disappear from the 5 and 10. They were quite expensive, because they were actually solid iron figures about 3 inches tall. They were made in all sorts of soldierly forms, a marine, an admiral, a sailor and so on. And also there were Indians and cowboys. And also there were pirates, there was quite a variety, although all of them were men, males, though there was one cabin boy.

Nothing was choreographed beforehand. We just went down and there were three or four certain figures that sort of belonged to me and to each one of us, especially belonged. And we were in charge of the house in which they lived. Or we spoke for them. And then there were others who were not attached to any of the three of us and anyone could speak for them. So, we just began and we had little dramas. Someone would walk down the street and someone would call out to him and—the truth is, I really don't remember any particular event or thing—but we soon fell into that world and I don't know how far my siblings fell, but I fell all the way into that world.

That was the first time in my life that I really experienced transcendence of consciousness or something like that. When my mother's voice came down the stairs telling us it was time to go to bed or whatever it might be, it was a shock to me. There was this world that I belonged to and then to discover that one or two or three hours had passed while we were doing this was also a shock, because that time had been separate from ordinary time. So I was really in the trance of another world when I played that game.

And then later in my life, when I started writing, I noticed something that I connected with that trance, when I was really involved with a poem I entered the world of the poem and then suddenly I realized that I had missed a dentist appointment or something, when someone called me up and woke me from that spell. [phone interview, July 3, 2003]

Kinnell told Michele more about the worldplay of writing poems. What he had to say informed a great deal of her understanding of imaginative play in poetic art, some of which (like the passage above) found its way into her book, Inventing Imaginary Worlds. And some of which didn’t, like this insight into the blurring of work and play in artistic composition:

GK: I think it’s like that—that work is play. Poetry involves the sounds of words so much, that just trying to get the sounds to relate to the thing, to express the thing you are writing about, and at the same time to relate to the sounds of the other words around them so it forms a musical line, that kind of play. But it doesn’t seem like play at the time of doing it, but part of the whole construct of the work, and even though the work might be extremely serious and even morose, still there’s that element of play that is just an inseparable part of it. [phone interview, July 3, 2003]

Poetry is that much richer for the paradox and for the worldplay that inspires and sustains it. So, too, is the eating of oatmeal.

© 2014 Michele and Robert Root-Bernstein

For more on Stevenson’s imaginary worlds or the Worldplay Project with MacArthur Fellows, see Michele Root-Bernstein, Inventing Imaginary Worlds: From Childhood Play to Adult Creativity.