Adolescence

Multiple Causes of Increase in U.S. Teen Suicides Since 2008

Why did teen suicides increase in the U.S. beginning in 2008, but not in Europe?

Posted November 28, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

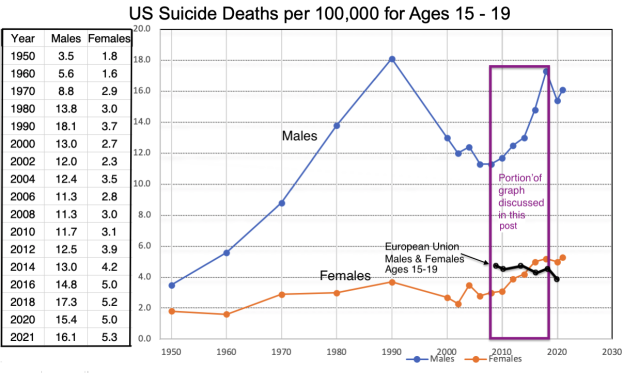

This is the eighth (and maybe the last) in my series of posts aimed at understanding the causes of changes in suicide rates among U.S. teenagers from 1950 to the present, which are depicted in the graph below the next paragraph.

The first post introduced the graph and solicited readers’ theories about the causes of the depicted rise, then fall, then rise again in suicide rates. In the second I discussed the sex difference in suicide rate (why it is much higher for boys than girls) and summarized evidence that the continuous rise in suicides from 1950 to 1990 resulted from a continuous and overall large decline in opportunities for kids to engage in the sorts of independent activities that are essential both for immediate happiness and development of the courage, confidence, and sense of agency required to meet life’s challenges. In the fourth I expanded on the message of the second by describing the social changes from 1950 to 1990 that gradually deprived kids of the independence and freedom they had enjoyed in earlier decades.

In the third post I presented reasons to believe that the decline in suicide rate between 1990 and about 2005 resulted, at least in part, from the availability of computer technology and video games that brought a renewed sense of freedom, excitement, mastery, and social connectedness to the lives of children and teens, thereby improving their mental health. In the fifth post I presented strong reasons to believe that the sharp increase in suicide rate from about 2008 to 2019 (the year before the COVID pandemic) resulted at least partly from increased school pressure brought on by No Child Left Behind and then Common Core. In the sixth and seventh posts I presented evidence from many studies countering the popular hypothesis that the rise in suicides after 2008 was caused largely by teens’ heavy use of digital technology, especially smartphones and social media.

Now, in this post, my intention is to present a more complex account of the mix of social forces that caused teens’ suicides and mental health problems generally to increase beginning about 2008. I will provide more evidence supporting the school-pressure hypothesis, introduced in the fifth post, but will place that in a context of other social changes that may have increased young people’s fears about the future and promoted a growing sense of helplessness and hopelessness.

A Post-2008 Rise in Teen Suicides Did Not Occur in Europe

A line of evidence against the smartphone/social media hypothesis that I did not introduce in previous posts is that teens pretty much everywhere have smartphones and access to social media, but the suicide rate for teens has not increased in other countries as it has in the U.S. As just one example, the growth of teens’ smartphone use in Germany over the years in question was comparable to that in the U.S. (see here), but there was no increase in suicide rate among German teens over these years. In fact, the same can be said for all 27 countries of the European Union (EU) taken as a whole. Using data I downloaded from Eurostat, I plotted the change in suicide rate for teens ages 15 to 19 for EU countries as a whole from 2009 to 2020—with black dots and lines—on the same graph (above) where the U.S. data are plotted. As you can see, while suicide rates for U.S. teens were rising sharply, rates for EU teens were essentially unchanged or even declining slightly. I was unable to get the database to break the EU teen suicide rates down by gender, so the plot shows average rates for males and females combined.

Other research, using other measures, has likewise shown that mental distress among European teens did not increase by anything close to the degree it did in the United States. For example, one study—using data from large surveys of teens conducted every four years from 2002 to 2018 in 36 mostly European countries—concluded: Overall, we found a small but significant increase in psychosomatic health complaints and no overall change in life satisfaction. Based on these two indicators, our findings do not provide evidence of a dramatic decline in mental well-being at the population level, as the effect was rather small. (Cosma et al., 2020).

So, one way of thinking about the sharp decline in mental health of U.S. teens since 2008 involves asking: What happened in the U.S. that did not happen in Europe, which could possibly affect teens’ mental health?

School Pressure, Achievement Pressure, and Lack of Economic Safety

In the fifth post in this series I cited surveys showing that, by a large margin, U.S. teens themselves attribute their high levels of psychological distress primarily to pressures associated with school. I also cited studies showing that teens’ anxiety, psychological breakdowns, and suicide rates have, in the years under consideration, plummeted during school vacations and risen again when schools reopened. I also referred to research showing that teens attending “high achievement schools,” where high grades and an impressive résumés are most valued, are even more prone to anxiety, depression, and suicidal behavior than are teens at other schools. I suggested that the increased focus on test drill, with consequent reduction in more enjoyable and creative school activities, brought on by No Child Left Behind and Common Core, increased the aversiveness and stress of school at the time when teen suicide rates began to increase.

Subsequent to my publication of the fifth post, one of the most influential advocates for the smartphone/social media hypothesis attempted to dismiss the school-pressure hypothesis (here) by referring to a study indicating that time spent on homework did not increase for high school students and may have even decreased a little for middle school students over the years in question. Another study, however, conducted by the Pew Research Center, showed a significant increase in time spent on homework over those years, especially for girls (Livingston, 2019).

More to the point, however, I don’t think time spent on an activity is a reasonable measure of psychological distress about that activity. It doesn’t take much insight into human psychology to realize that we often avoid activities that make us anxious and unhappy. Increased school pressure, and increased distaste and anxiety about schoolwork, may have led some to spend more time on homework and others to spend less time on it, resulting in relatively little change in averages.

A few years ago (in 2015) I published an article about the decline in emotional resilience among college students, in which, among other things, I described reports of emotional breakdowns after receiving a low grade on a test or paper, which for some was anything less than an A. The post generated hundreds of comments, some of which were from college students and a few from high school students. What struck me in reading the students’ comments was the anger they expressed about what they perceived to be societal pressure on them to achieve high grades even at the expense of genuine learning. Here are a few examples, quoted from the comments:

• Anything less than an A was unacceptable, and it was ingrained in us early on by our parents that perfection was our only chance for success in this competitive world. This article mentions students having anxiety and considering even a B grade to be a failure—that's why. I've definitely experienced that pit of hopelessness in my stomach any time I received less than an A grade.

• I hate reading articles about how our generation is too needy and has been coddled. You know what made us think we have to get all As? Our parents, our scholarships, our teachers, and the internet.

• You say you want people to learn? It's OK to get a B? BS. You want only the 'very best.' What you mean is the people that can grind out As. Yes, I got my As but was extremely unhappy while in school.

• They tell you that good grades are not enough, that getting all As is simply the bare minimum. You need to be a member of at least two organizations, but being a member is not enough, you must be leadership. ... At every corner you are told simply learning and doing your absolute best is not good enough. Instead of the focus being on learning the material and growing through the experiences, you are told what you are doing is worthless unless you can beat other students. Everything you do is measured against how other people are doing. You must constantly prove you are better than the other students.

These examples are no doubt extreme cases, and they exaggerate the degree to which school grades really do affect one’s future, but perception is psychological reality. These quotes illustrate a more general view that young people have about the competition that is forced on them by the school system and society in general. They have been led to believe they will be failures in life if they do not score better than their peers on measures they did not choose and that make no sense to them.

In the fifth post I presented evidence that the obsessions with grades and test scores were augmented by Common Core around the time when suicide rates began to increase. Another societal event around that time was the Great Recession of 2008 to 2009, which involved a sudden large increase in unemployment, loss of many people’s savings (as stock markets tumbled), and, psychologically, loss of people’s faith in the economy.

Of course, the Great Recession occurred in Europe as well as in the United States, but there are reasons to believe it had a larger psychological effect on U.S. citizens than on EU citizens. European countries generally have more government-supported programs to keep people out of poverty—such as universal medical coverage, unemployment protections for workers, and highly progressive tax rates—than does the United States. It is easier to fall from wealth to poverty, from having a home to homelessness, in the United States than in Europe. The Great Recession may have caused a marked increase in U.S. parents’ worries about their children’s economic future—worries that may have lasted for years after the recession ended and still be present.

Increased anxiety about their children’s future, coupled with a preexisting U.S. emphasis on competition and a growing belief that the competitive arenas for kids are schools and other adult-controlled, adult-judged activities that could contribute to a résumé for college or employment, led parents to become more involved with and anxious about their children’s school and extracurricular achievements than they had been before, thereby contributing to the anxiety and pressure experienced by the kids. This is speculation, but quite reasonable speculation. It can help explain why a decline in teens’ mental health occurred much more markedly in the United States after 2008 than in Europe.

A good deal of research shows that socially imposed expectations for achievement can lead to internalized perfectionism, which can lead to psychological collapse, because, after all, perfection is never possible (Curren & Hill, 2022). No achievement is good enough. All this is quite consistent with the findings that students at high-achievement schools have suffered more psychologically than those at other schools. It is also consistent with the finding, in the APA study I referred to in the fifth post, that the second greatest source of stress cited by the teens surveyed—after school pressure—was “getting into a good college or deciding what to do after high school.”

Are We Teaching Helplessness to Young People and Over-Sensitizing Them to “Trauma”?

At the expense of complicating the argument further, another reason for the decline in mental health among teens since 2008 may have to do with the way we, as a society, have reacted to kids’ distress. As we adults have taken over ever more of kids’ lives, allowing them to do ever less on their own away from us, we have become ever more involved with their emotional experiences as well as all their other experiences. In the process we may have sensitized kids to negative emotional experiences in ways that exaggerate their negativity.

Teasing may be seen as “bullying.” A flirtatious touch or comment may be seen as “sexual abuse.” These may become disturbing, or even “traumatizing,” to the degree that we, or society in general, teaches that they should be disturbing or traumatizing. At the extreme, if one begins to see every annoying question or comment as a “microaggression,” one might begin to believe they are in a sea of attack. Where once adults taught kids to recite sticks and stones can break my bones but words can never hurt me, adults today are more likely to focus their teaching on ways that even relatively innocuous words can hurt.

Moreover, the repeated suggestion to kids that they should talk to a counselor or other authority about any problem they have sends the implicit message that they are unable to solve their own problems. We may in that way be teaching kids that they are fragile and helpless rather than resilient and competent. When such disempowering messages are combined with restrictions on kids’ independent play and activity—the traditional ways that kids have learned to solve problems on their own—the messages may be doubly effective in convincing kids that they are helpless. Helplessness, which is a primary component of anxiety, can lead to hopelessness, which is almost the definition of depression.

Of course, there are two sides to all this. There is real bullying and real sexual abuse, which have long been problems too shrouded in secrecy. And there are times when a person may need help from a therapist or counselor to deal psychologically with a problem. But we may have carried good intentions too far in the messages we send.

In a recent essay in The Atlantic, the feminist writer Jill Filipovic (2023), expressed some regret for her past support of “trigger warnings,” founded on the premise that even the mention of something hurtful in a lecture or in everyday conversation can create psychological harm in the listener. She pointed out that “by 2013 [trigger warnings] had become so pervasive—and controversial—that Slate declared it “The Year of the Trigger Warning.” She went on to write:

“In giving greater weight to claims of individual hurt and victimization, have we inadvertently raised a generation that has fewer tools to manage hardship and transform adversity into agency? … Applying the language of trauma to an event changes the way we process it. That may be a good thing, allowing the person to face a moment that truly cleaved their life into a before and an after, and to seek help and begin healing. Or it may amplify feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, elevating those feelings above a sense of competence and control. …A person’s perception of themselves as either capable of preserving through hardship or unable to manage it can be self-fulfilling.”

I agree.

Concluding Thoughts

I began this series of posts weeks ago because I was concerned about the voices proclaiming that the problem of teens’ mental health is all about smartphones and social media. If we would just take these away from kids, or limit their use in some way, we could solve the problem.

These voices have been popular, regularly quoted in the press, because they feed into our society’s almost automatic, reflexive way of thinking about kids. If kids have a problem, the problem must be the result of something kids are doing. To solve the problem, we must stop them from doing whatever that activity might be. We must deprive them of yet one more of their remaining means of independence. We adults are loathe to blame ourselves. We believe we are protecting kids by restricting their independence, and we believe we are educating them better through ever more restrictive schooling and school-like activities outside of school. When kids themselves tell us something different, we ignore them.

Compared to the task of changing social structures so kids can once again play and explore independently, which they must do to grow up happy and resilient, and compared to the task of truly reforming schools, so they work with kids’ natural ways of learning rather than against them, and compared to the task of changing social structures to emphasize the value of cooperation more than competition, taking kids’ smartphones away is easy. But that won’t solve the problem. It’ll make it worse.

As always, I welcome your thoughts and questions. Psychology Today does not allow comments, so I have posted this on a different platform where you can comment. I invite you to comment here.

References

Cosma, A., et al. (2020). Cross-national time trends in adolescent mental well-being from 2002 to 2018 and the explanatory role of schoolwork pressure. Journal of Adolescent Health 66 (2020) S50eS58.

Curren, T., & Hill, A.P. (2022). Young people’s perceptions of their parents’ expectations and criticism are increasing over time: implications for perfectionism. Psychological Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000347.

Filipovic, J. (2023). I was wrong about trigger warnings: Has a national obsession with trauma done real damage to teen girls? The Atlantic, Sept. 2023 issue.

Livingston, G. (2019). How teens spend their time is changing, but boys and girls still differ. Pew Research Center Feb. 20, 2019.