Suicide

Why Did Teens' Suicides Increase Sharply from 2008 to 2019?

Evidence suggests that changes in schooling seriously hurt kids' mental health.

Posted October 22, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

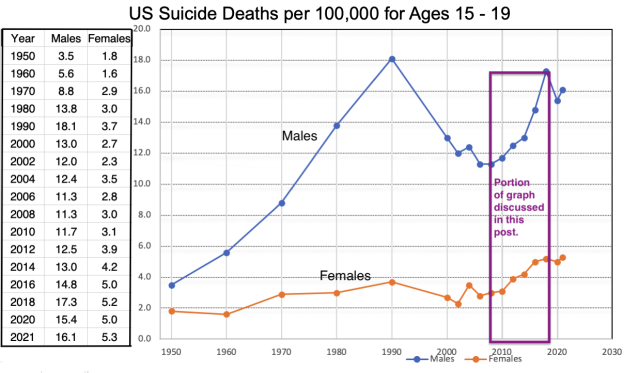

This is the fifth in a series of posts, aimed at understanding the causes of the changes in suicide rates among U.S. teenagers from 1950 to the present, which are depicted in the graph shown here:

In the first in the series I introduced the graph and solicited readers’ theories about possible causes of the changes in suicide rates depicted. In the second I discussed the sex difference in suicide rate (much higher for boys than girls) and presented evidence that the continuous rise in suicides from 1950 to 1990 resulted from a continuous large decline over this period in opportunities for kids to engage in the sorts of independent activities that are essential both for immediate happiness and development of the courage, confidence, and sense of agency required to meet life’s challenges without falling apart. In the fourth I expanded on the message of the second by describing the social changes from 1950 to 1990 that gradually deprived kids of the independence and freedom they had enjoyed earlier.

In the third I presented reasons to believe that the decline in suicides between 1990 and about 2005 resulted, at least in part, from the availability of computer technology and video games that brought a renewed sense of freedom, excitement, mastery, and social connectedness to the lives of children and teens, thereby improving their mental health.

Now, in this post, I present and support a theory about the final portion of the suicide curves shown the graph, the sharp increase in suicides from about 2008 to 2019 (the year just before the COVID pandemic).

My theory, in brief, is that during this period schooling became far more stressful and damaging to mental health than it had been before, and this resulted in increased rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide among students. The damaging changes in schooling resulted from the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act, which became U.S. law in 2002, and the Common Core Standards Initiative, introduced by the federal government in 2010 as follow-up to NCLB.

In support of the theory, I present here evidence that (a) NCLB and Common Core indeed did alter schooling in ways that would reduce the fun and increase the pressure; (b) children and teens themselves attribute their high levels of stress and anxiety more to school pressure than to any other cause; (c) rates of attempted and actual suicides for students are much higher when school is in session than when it is not; and (d) academic training and testing in preschool and kindergarten—brought on by NCLB and Common Core—have long-term harmful effects on children’s development.

No Child Left Behind and Common Core Reduced the Enjoyable Aspects of School and Augmented the Stressful Aspects.

Researchers who have reviewed the effects NCLB and Common Core have uniformly pointed out that these interventions markedly altered the nature of schooling. They brought a more rigid curriculum and high stakes testing to most schools, and the tests began to be used not just to evaluate students but also to evaluate teachers and whole school systems. Teachers no longer felt free to adjust the methods and content of their teaching to accord with the interests and needs of their students. They now felt compelled to teach in ways that would, they hoped, increase scores on the mandated tests.

In the belief that more time drilling would produce higher test scores, recess and subjects for which there was no mandated test, such as music and art, were reduced or eliminated in many schools. By 2014, according to a survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ((2015), the average time spent per day in recess (including any recess associated with the lunch period) for U.S. elementary schools was just 26.9 minutes, and some schools had no recess at all.

Reviews of how schooling changed over the period following these federal interventions have regularly pointed to a reduction in creative and enjoyable activities and increased focus on drill for high-stakes tests. One reviewer (Will, 2019) wrote: “Teachers say they feel like teaching has become more prescriptive, and there’s less room for creativity. Some say the intense focus on standardized test scores and student data has made it harder to build relationships in the classroom.”

Another reviewer (Jarrett, 2019) wrote: “I think the current situation is sad. It is stultifying, especially in schools in high-poverty neighborhoods. There is very little fun at all. These schools are under pressure to increase test scores, and they spend too much time with “skill and drill” test-prep activities. In some of these schools, the teachers’ salaries depend on the students’ test scores, pushing some teachers to teach to the test and give lots of homework in hopes that test scores will rise.”

In Surveys, Kids Say School Is the Primary Source of Their Distress.

There’s an old saying in humanistic psychotherapy that goes something like this: “If you want to know what is bothering someone, ask them.” Concerning the rise in anxiety and depression among kids in recent years, adults have produced a variety of guesses, based on their own suppositions. But if you ask kids themselves, you get a remarkably consistent answer. What’s bothering them is school. Here are the results of the relevant systematic national surveys I have been able to find, all conducted after the onset of Common Core:

• In a Pew Research survey published in 2019, which asked teens about the pressures they and their peers face, 61% responded that “getting good grades in school” caused “a lot” of pressure, and an additional 27% said it caused “some” pressure. No other cause came close to those numbers in the teens’ responses.

• In a Harris Poll, published in 2023, surveying children ages 9 to 13 about their most common worries, 64% cited concerns about school performance. No other concern approached this level.

• A large, demographically balanced survey of “Stress in America,” conducted in 2013 by the American Psychological Association. concluded that teenagers in school are the most stressed-out people in the country. In the survey, 83% of the teens cited school pressures as a cause of their stress. The next leading cause was “getting into a good college or deciding what to do after high school,” cited by 69%. Nothing else came close. Equally telling was the finding that when teens were surveyed during the school year, 27% reported experiencing recent “extreme stress” compared to 13% when surveyed during summer vacation.

Interviews and a Facebook survey of teens and parents, by National Public Radio in 2013, about sources of stress on teens, gave voice to the statistical findings above. Here are some examples:

• A high school junior was devastated to see that she didn't get a perfect 4.0 on her report card. The mother reported, "She had a total meltdown, cried for hours; I couldn't believe her reaction."

• To the Facebook question about stress, a 16-year-old wrote: “This year I spend about 12 hours a day on schoolwork. I'm home right now because I was feeling so sick from stress I couldn't be at school. So, as you can tell, it's a big part of my life!”

• Another wrote, of the stress of school: “It's a problem that's basically brushed off by most people. There's this mentality of, 'You're doing well, so why are you complaining?'” This student wrote further of experiencing symptoms of stress in middle school and being diagnosed with panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in high school.

• And another wrote: “Parents are the worst about all of this. All I hear is, 'Work harder, you're a smart kid, I know you have it in you, and if you want to go to college, you need to work harder.' It's a pain.”

Still further evidence of the role of school pressure in teens’ mental breakdowns derives from research by Suniya Luthar and her colleagues showing that rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide attempts are much higher for students at “high-achievement schools” than for those at more typical schools. High-achievement schools were defined by the researchers as those where test scores are especially high and a large percentage of graduates go on to elite colleges. The academic pressure at such schools is especially high and so are the rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal behavior. For more on Luthar’s research, see my post here.

The pressure on students derives not just from the school workload but even more from the continuous evaluation of their performance and the students' perception that their self-worth depends on how well they are doing in school. Many have become convinced that a low grade, even in a single course, will destroy their future.

Rates of Students’ Suicides and Suicide Attempts Plummet When School Is Not in Session.

Research conducted in recent years has shown that rates of mental breakdown and suicide are much higher for students during months and weeks when school is in session than during vacations from school.

Collin Lueck and his colleagues (2015) tabulated rates of psychiatric visits at a large pediatric emergency mental health facility in Los Angeles on a week-by-week basis for the years 2009-2012. They found, overall, that the rate of such visits in weeks when school was in session was 118% greater than in weeks when school wasn’t in session. In other words, the rate of emergency psychiatric visits during school weeks was more than double what it was during non-school weeks.

A sharp decline in such emergencies occurred not just during summer vacation but also during school vacation weeks over the rest of the year. The researchers also found a continuous increase in the rate of such emergencies over the four-year period of the study during school weeks, but no such increase during vacation weeks. This is consistent with the idea that school became more stressful with each year from 2009 through 2012, but life outside of school did not.

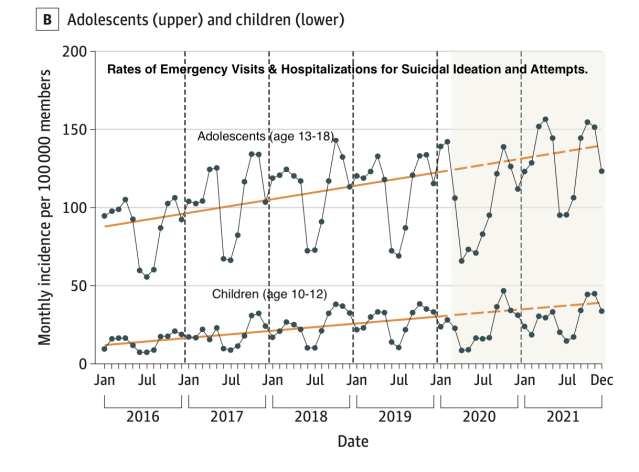

Youngran Kim and colleagues (2023) used a large database of health insurance claims to chart the month-by-month rates of emergency mental health admissions for suicidal ideation or attempts for teens ages 13 to 18 and children ages 10 to 12, across the country, for the years 2016 through 2021. The results are depicted in the figure below, taken from the research report. As you can see, the rates of emergency visits were much greater for teens than for younger children, but for both groups the rates were much higher during school months than during the vacation months of June, July, and August.

It’s worth noting, in this graph, that in 2020 the rate of admissions dropped sharply in March, April, and May, unlike in other years. Those were months when most schools were closed because of COVID, and several research studies (which I reviewed here) revealed that mental health among students overall improved during those months. This observation runs counter to dire predictions by some that the lock-down would be psychologically devastating to kids but is consistent with other evidence that students’ mental health improves when school is not in session.

In a large study conducted for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Benjamin Hansen and colleagues (2022, here) examined rates of teen suicides month-by-month over years. They found a pattern for actual suicides very similar to that found by others for suicide attempts. Suicide rates were much higher during school months than during vacation months. By comparing suicide rates in different counties across the nation, they showed that the timing of increased suicides corresponded closely with the timing of school openings. In areas where schools opened in August, suicides began to increase in August. In areas where schools opened in September, suicides began to increase in September. They also found that teen suicides plummeted in the middle of March, 2020, when schools closed for COVID, and remained low until schools reopened for the following school year.

In the graph near the top of this post you can see a brief decline in suicide rates from 2019 to 2020. That decline reflects the decline in teen suicides in the months of school lockdown.

Academic Training in Preschool and Kindergarten Has Been Shown to Cause Long-Term Harm.

To fully understand the damage to kids’ mental health resulting from NCLB and Common Core we must also consider the ways that kindergarten and preschool changed because of these federal interventions. Whereas kindergarten was once primarily a place for children to play and adapt to being away from home and with other kids, after NCLB and Common Core it became increasingly a place where kids are supposed to acquire the literary and numeracy skills that were formerly introduced in first grade (Repko-Erwin, 2017). And now, increasingly, even tots in many preschools are being required to spend hours per day at “academic” seatwork, in the belief that this is necessary to prepare them for the rigors of kindergarten!

I’m often invited to speak at conferences of preschool and kindergarten teachers, and many of the attendees express outrage and disgust at what they are required to do to little children in their classrooms. Many of the best teachers have resigned. I have previously discussed teachers’ reactions to these changes in detail here and here.

All the research studies I’ve been able to find that examine long-term effects of such early academic training have found that the effects are negative. Experiments comparing students who were in academic preschools or kindergartens with those who were in play-based preschools or kindergartens have routinely shown that by third grade and beyond, the former are socially, emotionally, and even academically disadvantaged compared with the latter. I reviewed some of these studies here and here.

The most rigorous, well-controlled such study was of an academically based preschool program in Tennessee, designed for children of families below the poverty line. Because more families signed their children up for the program than could be accommodated, a random lottery was used to determine who would be in the program and who wouldn’t. This provided the perfect conditions for a controlled experiment. Researchers at Vanderbilt University followed the children in both groups over subsequent school years up through grade 6 (Durkin et al., 2022).

The major finding was that children who had been in the program were, by 6th grade, performing more poorly by every measure than those who were not in the program. They performed more poorly on all academic achievement tests (in reading, math, and science). Most significant, they were nearly twice as likely by 6th grade to have been diagnosed with a learning disorder compared to those who were not in the program. They also showed significantly more behavioral problems, including rule violations and fighting in school, than those in the control group.

It seems quite possible to me that forcing little children to abide by the new preschool and kindergarten curricula is, for some children, traumatic child abuse, which makes them feel they are failures and burns them out about school and maybe other aspects of life before they have really started. I would not be surprised if children in the Tennessee preschool program, now teenagers, are more likely to feel suicidal than those who were kept at home in their economically impoverished families that year.

Conclusion and Further Thoughts

Compulsory schooling, where students are forced to learn (or go through the motions of learning) in ways that do not match their natural ways of learning, has never been good for children’s and teens’ mental health (see Gray, 2013). But changes brought on by No Child Left Behind and Common Core have clearly made schools worse in this regard than they were before. Children’s and teens’ own reports, and the timing of mental breakdowns and suicides over the school calendar, make it clear that school has become a major source, if not the major source, of psychological distress for American children and teens.

This is a difficult conclusion for most adults in our society to reckon with. Most adults would rather attribute young people’s distress to almost anything else. The research studies I have described here are almost never reported in the popular press. A tiny correlation between social media use and anxiety in girls gets major press coverage with sometimes dramatic headlines, but a study showing that 83% of teens cite school pressure as a major source of distress, far more than any other cause, or that teens’ rates of mental breakdowns and suicides are about twice as high when school is in session as when it is not, gets essentially no coverage at all.

There seems to be, in our society, a taboo against admitting that school creates mental distress in the majority of students. School is something that we, the public, have imposed upon young people, so to blame schooling is to blame ourselves, and that is hard. It is far easier to blame those profit-seeking social media and video game companies.

If you attend to the popular press and avoid careful reading of the actual research literature, you are likely to believe that new technology is the primary cause of young people’s distress. I intend in a future post to take a hard look at the research evidence, exaggerated by the popular press, that social media, or iPhones, or screens in general are causing today’s epidemic of anxiety, depression, and suicide in young people. Stay tuned.

As always, I welcome your thoughts and questions. Psychology Today does not allow comments, so I have posted this on a different platform where you can comment. I invite you to comment here.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). School health policies and practices study: 2014 overview. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Durkin, K., Lipsey, M.W., Farran, D.C., & Wiesen, S.E. (2022). Effects of a statewide pre-kindergarten program on children’s achievement and behavior through sixth grade. Developmental Psychology, 58, 470-484.

Gray, P. (2013). Free to learn: Why releasing the instinct to play will make our children happier, more self-reliant, and better students for life. Basic Books.

Jarrett, O. (2019). From playing to play advocacy: An interview with Olga S. Jarrett American Journal of Play, 11, 145-155.

Kim, Y., Krause, T.M., & Lane, S.D. (2023). Trends and seasonality of emergency department visits and hospitalizations for suicidality among children and adolescents in the US from 2016 to 2021 JAMA Network Open, July 19, 2023.

Lueck, C., et al. (2015). Do emergency pediatric psychiatric visits for danger to self or others correspond to times of school attendance? American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 33, 682-684.

Repko-Erwin, M.E. (2017). Was kindergarten left behind? Examining US kindergarten as the new first grade in the wake of No Child Left Behind. Global Education Review, 2, 58-74.

Will, M. (2019). Teaching in 2020 vs. 2010: A look back at the decade. Education Week, Dec. 10, 2019.