Memory

Forgetting Sorrowful Moments

How can we erase memories of harmful happenings that tend to linger?

Posted March 10, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Life is a sequence of memories, some solidly enshrined in the hippocampus, and some ready to be deleted.

- People with hyperthymesia or autobiographical memory may struggle with not being able to delete harmful long-term memories.

- The technique of cognitive reframing can help people rid themselves of unwanted memories.

My blog posts fall under the umbrella title The Speed of Life. My most recent posts have been about controlling thoughts and harrowing memories. In this one, I’m crossing another line that separates thoughts from comprehension and brings together a triptych—reflections, remembering, and forgetting.

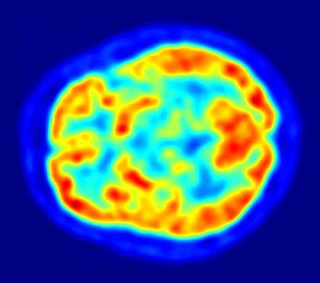

Memories can harrow, yet also be forgotten. Time has erasure power or the control to blur matters harmful to the mind and body. It is an influencing arbitrator that listens without too much bias to all psyche troubles. It judges what stays pigeonholed in the hippocampus and what is deleted.

Time is also tuned to practice. The 19th-century German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus conceived a mathematical model of how memory retention drops over time—The Forgetting Curve. Ebbinghaus concluded by experimental studies that unless a person continues to review, material retention will diminish inversely proportional to time measured in days.

When I was young, going back to—I forget how many years ago—I read Alexander Luria’s short nonfiction book, The Mind of a Mnemonist. Luria was a Soviet neuropsychologist who for 30 years studied Solomon Shereshevsky, a journalist who had a super-spectacular memory. At one of his first appointments, Luria asked Shereshevsky (let’s call him S, as Luria did in his book) to read a copy of the first canto of Dante’s Inferno in ancient Italian, a poem of over a thousand words in a language that made no sense to S. Soon after, Luria asked S if he could remember the canto. S recited it precisely. Ten years later, Luria asked again, and once again, S repeated the canto as if he had just read it.

What might seem like a gift turns out to be a curse. S’s hyperthymesia condition caused distractions of irrelevant images or thoughts. He was limited in reading novels because he would get tripped by keeping incidentals in his head. A lit cigarette continuing to burn in an ashtray in one scene would trouble him in the next.

For some people, forgetting is a more difficult task than remembering.

In my last post, I wrote about haunting memories one might wish to forget. The problem with trying to forget is that memories are cataloged in a one-way field of dendrite spikes in the hippocampus. Once accepted through filters and gauntlets of the conscious-subconscious loops when we sleep and dream, memories rest in their long-term niches until events more important to the body replace them. They do not easily let go. Some are suppressed or repressed. As you know, suppressions and repressions can sometimes be protections and other times mentally toxic.

Dreams, however, are the saviors. The path to forgetting is to dream. Dream away all your sorrows. That is why we dream. Sleep—ironically, the protector—is the key to forgetting. Memory has its purpose, as does forgetting. Without memory, we have no directions for behavior, no solutions to problems, and no plans because we have no rationale for learning from the past.

Consider my case of being born at the beginning of WWII when my father, at 35, enlisted as a private and fought in France. That war history is vivid for me and so too was the Korean War, only because my grandmother died on the same day of an announcement that the Korean War had ended. Those connections provided mileposts and VIP memories pigeonholed in my hippocampus; they made histories of those wars bold and capitalized.

So, how can we dispose of repeating unwanted thoughts?

S’s curse was the difficulty of forgetting trivial and irrelevant material. To forget a memory, he would burn a piece of paper on which he spelled out what he wished to forget. Sounds easy, but I suspect that for most of us, that would not work.

Fortunately, most memories fade in time. For those that don’t, the annoying ones, there are tools. Therapists know those tools and can help. They probe to find out what triggers a troubling recollection. It could be as innocent as a coincidental awareness of a color, a smell, a sound, a death of a loved one, or any one of a thousand prompts connected to a common emotion.

Consider how S, the mnemonist, innately used tricks to commit things to memory by associating colors, sounds, and numbers as labels for long-term recollection as if memories were being coded and filed in cabinets. Luria wrote that S would think of numbers as characters. “Take the number 1. This is a proud, well-built man; 2 is a high-spirited woman; 3 a gloomy person; 6 a man with a swollen foot; 7 a man with a mustache; 8 a very stout woman—a sack within a sack. As for the number 87, what I see is a fat woman and a man twirling his mustache.”

That method of remembering can also be a method of forgetting. If the memory is emotionally negative, try the cognitive reframing approach spinning it to a positive association. Remember, the brain can do amazing things under the power of heavy-duty concentration. For a general example, if a repeated annoying memory pops up by an association with a particular food, a piece of music, or the scent of a special flour, try disassociating the harm by mindfully replacing the set-off with one of the many moments when those same triggers afforded joy.

Remember the joys we tend to forget.

References

Schacter, D. L. (2009). Psychology. New York: Worth Publishers. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2.

A. R. Luria, The Mind of a Mnemonist, trans. by Lynn Solotaroff (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Luria, Aleksandr Romanovich; Lurii︠a︡, A. R. (1987). The mind of a mnemonist: a little book about a vast memory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-674-57622-5.