Highly Sensitive Person

Managing High Sensitivity, Then and Now

Part 3: How the treatment of high sensitivity has changed over time.

Posted January 18, 2022 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Our culture has continued to be troubled by emotional-sensorial experience for men and for women.

- Though their approached varied, Victorian doctors shared a common emphasis: curing hysteria and social-emotional sensitivity.

- Today there is more emphasis on the benefits of sensory processing sensitivity and a shift toward support and management rather than cure.

This is part 3 of a three-part series. Part 1 explored how Victorian and contemporary medicine talked about hysteria and HSP, respectively, as sensorial-emotional maladies. Part 2 discussed the purported causes for high sensitivity in the hysteric and in the HSP.

There was no end to “cures” for hysteria in the nineteenth century. From leeches to rosewater to vaginal suppositories, the number and type of cures rival the myriad purported causes. But despite the doctor’s different recommendations in their treatments, one thing remains consistent: all emphasized curing hysteria, rather than just managing it.

When it comes to treating today’s HSP, there are methods for coping with emotional regulation; however, the literature for the most part emphasizes the positives as well, suggesting that one would not want to eradicate but rather support one’s sensitivity for individual and social betterment. Seventy-one percent of the population claims to be either highly sensitive or moderately sensitive. [1] The shift away from cure for those on the high and medium scales of the HSP continuum signals a different regard for people’s everyday sensorial-emotional experiences.

Treating Hysteria in Victorian Times

Whereas some Victorian physicians sought to treat hysteria preemptively by bolstering up the general health of young girls, and others treated the perceived catalyst, still others focused on both the catalyst and relief of the accompanying symptoms.

For some physicians, the cure was in prevention. Since a disordered state of health was thought to be the root of environmental sensitivity by some physicians, they recommended parents watch over young family members to prevent causes and detect symptoms. [2]

Other physicians emphasized withdrawal, proposing that parents should keep girls and women away from possible triggers. [3] To stave off attacks, the theory went, a woman should keep clear of any mental, emotional, or environmental triggers.

Yet other physicians targeted treating depressed nerve-power once a woman already experienced it. [4] Just like theories of hysteria, cures differed. Yet most of the Victorian medical texts emphasized eradication of the nervous sensitivity.

How Is High Sensitivity Managed Today?

Today, studies are examining not only the negatives but also the positives of sensory processing sensitivity (SPS)—for the individual and for society. Newer literature challenges the diathesis-stress model or double-risk model to argue that something called vantage sensitivity exists. [5, 6, 7, 8] This means that individuals might experience overwhelm or unwellness in some situations but can also really thrive in other situations. In other words, they are not simply at risk but also at potential.

Research also suggests positive social effects of being highly sensitive: responsiveness to others’ emotions, trust, cooperation, etc. [9] Those on the high to medium sensitivity scale also exemplify attributes essential to certain careers such as therapist, writer, doctor, or teacher. Lastly, research has shown that an HSP’s aesthetic sensitivity (a heightened sensitivity and responsiveness to the arts) can enrich their lives. [10]

Given this shift to identifying some of the inevitableness and positives of SPS, there has also been a shift in discussions of management rather than cure. Given that SPS can lead to overarousal as well as physical ailments and depression or anxiety, the literature stresses “self-regulation”—but in a self-awareness and self-care way, not a policing or disciplinary way. [11]

Physicians and psychologists recommend certain strategies to help the person remain calm while stimulated. Tips are readily accessible on blogs and in periodicals. In one Psychology Today article, Haas provides 10 different suggestions for HSPs that include tips like wearing noise-reducing headphones and planning for decompression time. Certain recommendations, such as having a room to retreat to, echo to a certain extent the Victorian recommendation of removing the individual from stimuli—but here, the removal is temporary and planned, rather than the daily rule.

Elaine Aron’s monograph, Psychotherapy and the Highly Sensitive Person, outlines how therapists can help support their HSP clients. In Chapter 3, she provides strategies for helping the client navigate overarousal and strong emotional reactions. For work outside of psychotherapy, Aron provides The Highly Sensitive Person’s Workbook.

Her work also extends to those working with HSPs; Aron discusses tips for healthcare professionals working with highly sensitive people; tips for teachers working with highly sensitive students; and tips for employers of highly sensitive people in her 1990 monograph, The Highly Sensitive Person. Responsibility for negotiating sensitivity in our social interactions seems, Aron would suggest, to extend beyond the highly sensitive individual. Overall, Aron emphasizes and appreciates the advantages of SPS, so these strategies are couched in language of support rather than punitiveness.

What This Means for HSPs Today

The figure of the HSP preserves key concepts that have framed our understanding of the interplay between senses and health from Victorian times to the present.

What a comparison between the nineteenth-century hysteria discourse and the twenty-first-century sensory processing sensitivity conversation shows us is that our culture has continued to be troubled by emotional-sensorial experience for men and for women. While women are no longer maligned as the one gender exclusively prone to “fits,” men continue to report lower on certain HSP scale questions due, it is theorized, to cultural stereotypes. Nonetheless, the deviation from the diathesis-stress model and from the single-sex model is heartening, as is the narrative shift away from cure toward management.

Examining the discourse around sensory processing sensitivity in light of historical hysteria discourse raises the question: What do we do when there is no (or lessened, perhaps) medical pathology? When there is no narrative impetus toward a cure?

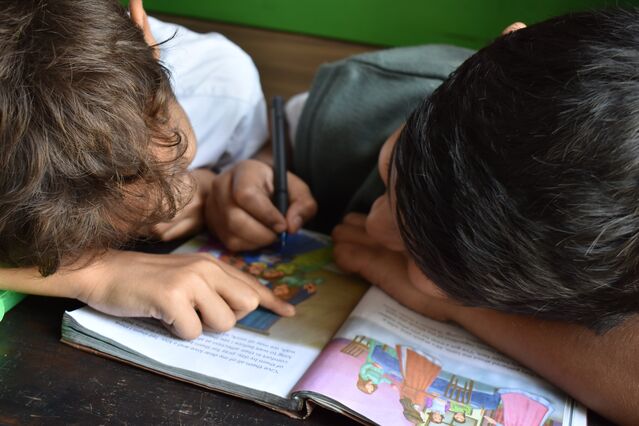

This shift away from thinking of people with SPS as disordered and mentally ill encourages us as a culture to reduce stigma and, instead, provide support. It spreads out the social responsibility of teaching affect regulation and supporting children’s emotional development both at home and through social and emotional learning (SEL) programs in school curriculums. If SPS is truly epigenetic, as recent research has suggested, environmental support is key.

As Boyce sees it, “[r]ecognizing this differential susceptibility is an essential key to understanding the experiences of individual children, to parenting children of differing sensitivities and temperaments effectively, and to fostering the healthy, adaptive capacity of all young people.” [12] And Elaine Aron and Arthur Aron are confident that “if raised in a supportive environment, [individuals with high sensitivity] would surely develop methods of affect regulation such that their emotional reactions would remain at a level that mainly enhances decision-making processes.” [13]

Though more research of course needs to be done, the big take-away is supporting the future of all young people. This involves shifting broader cultural stigmas around not only emotion and sensitivity in general but also pointedly for men and boys. The gender balance across the HSP scale flies in the face of Western culture that still critiques men’s emotiveness and sensitivity as anti-masculine and effeminate. This new HSP research asks us to shift away from the perception that women are simply more emotional or sensitive and to revise our approach to sensitivity in boys.

References

Acevedo, B., et al. (2018). The functional highly sensitive brain: A review of the brain circuits underlying sensory processing sensitivity and seemingly related disorders. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 373(1744), 1-7. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0161.

Acevedo, B.., et al. (2014). The highly sensitive brain: An fMRI study of sensory processing sensitivity and response to others’ emotions. Brain and Behavior, 1-15. doi: 10.1002/brb3.242

Aron, E. N., & Aron, A. (1997). Sensory-processing sensitivity and its relation to introversion and emotionality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 345–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.2.345.

Belsky, J., and M. Pluess. (2009). Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychol. Bull., 135, 885–908.

Boyce, W. T. (2019). Why some children are orchids and others are dandelions. Psychology Today.

Carter, R. (1853). On the pathology and treatment of hysteria. J. Churchill.

Hall, M. (1830). Commentaries: Principally on those diseases of females which are constitutional. Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper.

Hovell, D. (1867). On pain and other symptoms connected with the disease called hysteria. John Churchill & Sons, New Burlington Street.

Jagiellowicz, J. et. al. (2016). Relationship between the temperament trait of sensory processing sensitivity and emotional reactivity. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 44(2), 185–199.

Lionetti F. et. al., (2018). Dandelions, tulips and orchids: Evidence for the existence of low-sensitive, medium-sensitive and high-sensitive individuals. Translational Psychiatry, 8(24), 1-11. doi: 10.1038/s41398-017-0090-6.

Listou Grimen, H. and Å. Diseth. (2016). Sensory processing sensitivity: Factors of the highly sensitive person scale and their relationships to personality and subjective health complaints. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 123(3), 637–653.