Health

How the Fear of Getting Sick or Dying Can Motivate Change

Need motivation to exercise? Illness- and death-related messages get top marks.

Posted November 22, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Crafting persuasive nudges that motivate us to eat healthier, exercise more, and sit less is a Holy Grail-like quest for public health advocates.

- A new study suggests that illness- and death-related messaging may be one of the most effective ways to inspire healthy lifestyle choices.

- But not all "Debbie Downer" health messages work. Nudges that discuss the health care costs of obesity or body shaming don't motivate or inspire.

What motivates you? Do feel-good health messages that frame physical activity as a pathway to "greener pastures" make you want to lace up your sneakers and go for a jog? Or does doomsday scrolling through scorched-earth messaging that warns of all the horrible things that could happen if you don't start eating healthier, exercising more, and sitting less light a motivational fire in your belly?

Does the blissful allure of self-producing endocannabinoids, experiencing a runner's high, and feeling happy after a vigorous workout motivate you to seek regular physical activity? Or are you more motivated by the fear of sedentary-related illnesses and subconscious images of a scythe-wielding grim reaper ending your life early if you sit too much?

In many ways, exercise motivation is like a dual-edged sword or a yin-yang symbol with a "dark side" and a "bright side."

On the dark side, some people are motivated by all the negative things (e.g., depression, illness, death) that are more likely to happen if they don't get their blood pumping via physical activity and strength-training exercises most days of the week.

On the bright side, there's the "dangling carrot approach" of focusing on all the positive things that are more likely to happen (e.g., exercise-induced eudaimonia, increased brainpower, better memory, vitality, longevity) if you do get enough exercise each week.

Maybe “sweat = bliss” messaging isn’t the best way to motivate people?

The subtitle of this blog, "sweat and the biology of bliss," sums up my general philosophy and approach to exercise motivation. As someone who's spent my adult life trying to craft persuasive health communication that motivates people to exercise more and sit less, I've primarily focused on the feel-good (i.e., "sweat = bliss") aspects of working out.

As a general rule, I'm more interested in presenting the "greener pastures" that are available to every so-called "couch potato" if they start moving more than dwelling on the negativity of getting sick and dying prematurely if someone stays sedentary throughout his or her adult life.

That said, new research suggests that my optimistic and cheery approach to health messaging might be a little too Pollyanna-ish.

A recent Canadian study (Oyibo, 2021) examines how people respond to different health messages and "nudges" designed to motivate behavioral change via a fitness app. These first-of-their-kind findings were published in a special issue of the peer-reviewed journal Information called "Designing Digital Health Technologies as Persuasive Technologies."

Illness- and death-related health messaging kickstarts motivation.

During this study, the University of Waterloo's Kiemute Oyibo found that illness- or death-related messages are a highly effective way to kickstart people's motivation to make behavioral changes.

But pessimistic or grim health messaging doesn't always boost people's motivation to change their behavior. Oyibo's research shows that fitness app users weren't inspired to "sit less and move more" if the nudges emphasized obesity, nationwide health care costs of sedentarism, or the social stigma of being overweight.

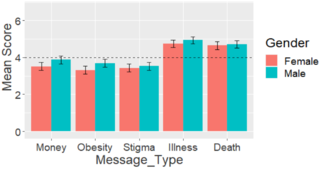

As you can see in the chart below, study participants weren't motivated by impersonal money-related public health messages (e.g., "Physical inactivity costs Canadian taxpayers $6.8 billion a year") or BMI-related messages like "One in four Canadian adults has clinical obesity." Shame-related messages about the social stigma associated with being overweight also didn't have a positive impact on people's motivation.

Unexpectedly, the men and women who participated in this study were most motivated by death-related messages, like "Six percent of the world's death is caused by physical inactivity," and sickness-related nudges, such as "Those who do not find time for exercise will have to find time for illness."

"I did not expect only illness- and death-related messages to be significant and motivational," Oyibo, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Waterloo's School of Public Health Sciences, said in a news release. "Not only were illness- and death-related messages motivational, they had a significant relationship with self-regulatory belief and outcome expectation, and there was no significant difference between males and females."

Oyiba notes that this study is significant because it can help public health advocates and those who design fitness and wellness apps to create more effective and persuasive health communication.

He also encourages future research to examine how other demographic characteristics beyond gender (e.g., age, culture, race, and education) influence exercise-related motivation. Knowing what inspires specific demographic groups to make lifestyle changes could help app designers create optimally persuasive health communication for targeted segments of the general population.

References

Kiemute Oyibo. "The Relationship between Perceived Health Message Motivation and Social Cognitive Beliefs in Persuasive Health Communication*" Information (First published: August 28, 2021) DOI: 10.3390/info12090350

*This paper is part of a special issue, "Designing Digital Health Technologies as Persuasive Technologies."