Dopamine

Tonic Levels of Dopamine Lubricate Moments of Superfluidity

Finding your sweet spot of dopamine production facilitates athletic bliss.

Posted September 2, 2016

As an ultra-endurance athlete, harnessing the power of dopamine to create a state of superfluidity—in which my mind, body, and brain operated with absolutely zero friction or viscosity—was the secret to my athletic prowess and sports success.

Through decades of physical and mindfulness training, I learned how to fine-tune just the right amount of dopamine pumping through my nervous system to manifest "sweat and the biology of bliss" on a daily basis. Dopamine regulation helped make the equation SWEAT=BLISS a reality for me, as it can for everybody. Tapping the power of dopamine was the key to having my training and competition never feel like torture or drudgery, but rather a rewarding labor of love.

Next week, neuroscientific thought leaders from around the world will be gathering in Vienna, Austria for the Dopamine 2016 Conference (Sept. 5-8). Matthäus Willeit of MedUni Vienna's Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, is organizing the Dopamine conference along with Harald Sitte. These researchers have been exploring the pitfalls of having too much or too little dopamine in your system. They also want to identify the sweet spot or "tonic level" of dopamine that optimizes psychological and physical well-being for every individual.

Willeit and Sitte have found that serious health problems can arise if too little or too much dopamine is being self-produced. For example, if too few dopamine molecules are released and in circulation, Parkinson's disease can develop. On the flip side, an excess of dopamine can lead to mania, hallucinations, and is associated with schizophrenia and addiction.

In this blog post, I offer some unconventional ideas about dopamine based on a hodge-podge of life experience, empirical evidence, and conversations with my father, Richard Bergland, who was a world-renowned neuroscientist and my mentor.

Based on observations and personal experience, I believe that many people can use a combination of moderate aerobic training and mindfulness meditation to fine-tune a personalized tonic level of dopamine on a daily basis. Of course, holistic remedies are not appropriate for all people in every circumstance. Please use common sense and follow the advice of your medical doctor or mental health professional to see if keeping your dopamine at a tonic a level requires pharmaceutical treatment.

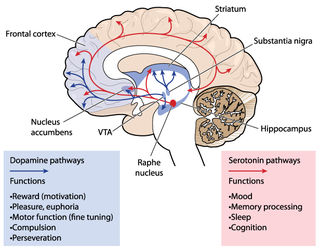

All Animals Seek Pleasure and Avoid Pain

Over a decade ago, I wrote extensively about dopamine in The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss. I refer to dopamine as “The Reward Molecule” because it drives pleasure seeking goal-oriented behavior via our dopaminergic pathways, which transport dopamine from one region of the brain to another. Segments of the passages below are adapted from “The Brain Science of Sport” chapter of my first book.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that facilitates achievement, goal-oriented behavior, motivation, mood, and movement. It causes that rewarding 'ding, ding, ding' jackpot feeling that floods your body when you win a prize or say "Yes! I did it." after accomplishing a goal.

Dopamine is released during exercise naturally; it is also the culprit for creating drug cravings and driving addictive behavior. Cocaine and other drugs hijack the dopaminergic pathways and fry dopamine receptors throughout the brain. The same ability of dopamine to make you feel like you're on top of the world can backfire and make you feel like you've hit rock bottom.

Through life experience, I've found that tapping into the infinite powers of dopamine helps to optimize my human potential and creates a feeling of transcendent ecstasy by taking me into a state of superfluidity. Neuroscientist, Robert Heath, once said, “All moral learning is ultimately based on the pain and pleasure circuitry in your brain and your internal reward-punishment system.”

In a statement, Harald Sitte of MedUni Vienna's Institute of Pharmacology, said, "Dopamine release is also responsible for people becoming addicted, in that they are always seeking pleasure so that they can reach higher and higher dopamine levels. Dopamine is the reason why a lot of people are constantly seeking to satisfy their cravings."

Eighty percent of dopamine is produced in a small region of the brain called the subsantia nigra (black stuff). Its axons thread like fire hoses through the brain, pumping dopamine to pleasure centers, where they cause a neural chain reaction that gives you a hit of ecstasy or reward. By creating clear-cut goals as you move through the day, you can release a continuous stream of dopamine. And avoid reward deficiency syndrome by consciously identifying goals and achieving them.

There is a growing consensus that the dopamine network influences everyday behaviors. Richard Depue, Ph.D., professor of human development at Cornell University, points out that goal-directed behavior, or the lack thereof, tends to present itself as a personality trait. One benefit of sticking with a moderate exercise routine is that it creates daily habits that keep the dopamine pumping and foster a healthy athletic mindset of setting a goal and achieving it.

Depue and others strongly believe that dopamine traveling along the reward pathways is the prime driving force that motivates most people's behavior. “When our dopamine system is active, we are more positive, excited, and eager to go after goals and rewards, whether it’s food, sex, money, education, or professional achievement,” he says.

Pursuing target behaviors, by single-mindedly focusing on a project, for instance, triggers the release of dopamine. Depue also suggests that people who are goal-oriented not only tend to be more motivated but are also generally happier. “We have strong evidence that feelings of elation [that occur] because you are moving toward achieving an important goal are biochemically based, though they can be modified by experience.”

Dopamine is what drives most athletes to set goals and achieve them. For example, back in my days of athletic competition, if I had a mission to qualify for the Hawaii Ironman—the joy of pouring every ounce of my energy into that long-term objective by achieving mini-goals day in and day out was incredibly rewarding. The actual race was actually just the icing on the cake for my journey of getting there.

Dopamine also facilitates motor learning and is key to fluid movement. Autopsies of people with Parkinson’s disease have shown that the black stuff of the substantia nigra appeared lighter in color, researchers made the connection between dopamine and fluid movement. Psychologically, I believe that dopamine is central to creating a state of flow and superfluidity. In order to achieve a tonic level of dopamine, set tangible goals and achieve them. Finish what you start—and you’ll release a hit of dopamine.

There is one important caveat. Too much dopamine can make a person manic or schizophrenic; too little results in the shaky physical movements of Parkinson’s. I have had delusions and hallucinations that are produced by an overload of dopamine after reaching my threshold of going for about twenty-four hours of nonstop exercise. Although I loved doing ultra-endurance sports in my youth, I have no desire to take my mind and body to the limit anymore.

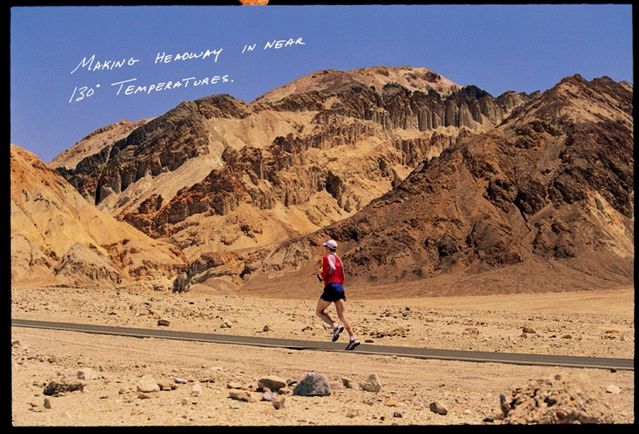

As an example, during the Badwater Ultramarathon in Death Valley, due to an overload of dopamine combined with heat exhaustion, I experienced the nerve-wracking illusion of snakes jumping out of rocks and psychadelic blankets of kaleidoscopic stars atop Father Crowley Point, which is the second five-thousand-foot climb that finally gets you out of Death Valley.

These hallucinations are a form of exercise-induced delusions triggered by way too much dopamine. Regular, daily, goal-oriented movement along with mindfulness and diaphragmatic breathing can help produce the perfect amount of dopamine.

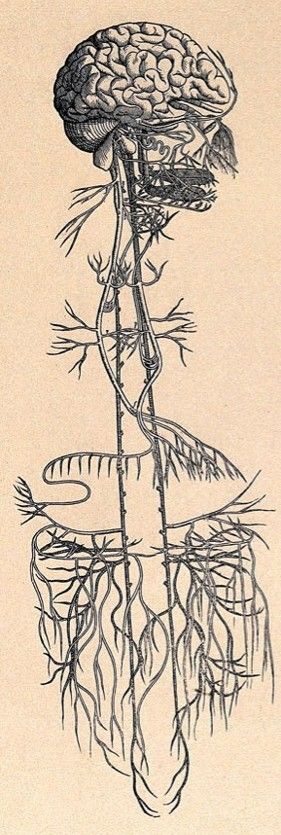

Engaging the Vagus Nerve Through Mindfulness Counters Dopamine-Fueled Mania

My father was a neuroscientist, neurosurgeon, and nationally ranked tennis player who taught me a lot about dopamine and how to have grace under pressure both on and off the court by consciously releasing acetylcholine to slow down my nervous system.

Ideally, a state of superfluidity is frictionless and lacking entropy because you aren't overexcited and don’t feel hypomanic or discombobulated. As an athlete, whenever I felt that I was getting too high on dopamine I would use meditation practices to bring myself back down to earth.

Although I don’t know of empirical studies to support my hypothesis, I learned through conversations with my dad and life experience that when I need to put the brakes on elevated levels of dopamine that if I relax the backs of my eyes and visualize my vagus nerve squirting acetylcholine onto my heart that I could engage my parasympathetic nervous system and calm myself down immediately. Again, this is strictly anecdotal.

Looking back on my lifelong relationship with having too much or too little dopamine, I realize that I’ve learned how to naturally find my tonic level through various types of practice. For example, I went to a high-pressure boarding school in Wallingford, Connecticut. My dean expected everyone to be wired with the same “Need for Achievement” ambitions, to get straight A’s, and to become a "Master of the Universe." I failed miserably.

The stodgy prep school environment beat me down and made me feel less than. At a certain point, I threw in the towel, embraced my amotivational syndrome, and decided to become a ne'er-do-well. I was filled with shame. Eventually, I turned to the dopamine-fueled rewards of drugs and alcohol as a way to cope with feeling like a total loser, outsider, black sheep, etc.

Because of my aversion to being judged for my extrinsic failures and lack of accomplishments at Choate—after high school, I enrolled at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts. Hampshire is one of the few colleges in America with absolutely no tests and no grades.

While at Hampshire, I got very into yoga and meditation. As a college student, I was fortunate enough to travel to India a few times as part of my studies. While there, I spent time in ashrams—where my only goal was to achieve a feeling of Nirvana by going into deep and extended trance-like states.

One way I would do this was by staring at a candle, relaxing the tonus of my tongue and the backs of my eyes while moving my head back and forth from side to side while focusing all of my attention on the flickering flame. I could sit still and stay in a trance like this for hours. Later in life, when I stumbled on my passion for triathlon, I would go to the same meditative head space that I discovered in India whenever I was running, biking, or swimming.

The Sanskrit word I would use to describe the transcendent feeling I get when I'm in a trance-like state and removed from the 3-dimensional world is pratyahara. I visualize this as unclamping my prefrontal cortex and seating my consciousness down into my cerebellum (Latin for "little brain"). The analogy I visualize is a turtle, which can pull its five appendages inside its shell and withdraw from the world. When the going gets tough for me—in sport or life—the place I go for sanctuary and refuge is deep inside my reptilian brain.

In discussing the phenomenon of feeling transcendent and describing how it felt to go into these meditative trances with my father, he planted the seeds in my head that I might somehow be activating the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) of my cerebellum in a way that created the opposite of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Again, this is speculative.

That said, I really liked the idea of creating a waking dream state that parallels REM sleep while I was running, biking, and swimming simply by activating the VOR system by locking my eyes on a target and moving my head from side to side. This technique worked for me as a way to get through dozens of ultra-endurance athletic competitions. Give it a try during your next workout. Maybe it will work for you, too?

Although what I've accomplished as an athlete might appear to be hyper-dopamine driven to onlookers, I always kept myself zen and grounded by using the tricks above. I have a hunch that without the techniques I learned to slow down my nervous system from years of meditation—and to keep my dopamine levels from skyrocketing too high—I wouldn't have had the grace under pressure to do what I did as an athlete.

For example, when I broke the Guinness World Record by running 153.76 miles on a treadmill in 24 hours, I created a tonic level of dopamine and superfluidity by going into a trance by staring at a small red light in front of me while moving my head from side to side. This unclamped my prefrontal cortex and put me in a cerebellum-driven meditative state. Again, if I allowed the overload of dopamine to build up too much, I would have completely gone into a hypomanic delusional state.

In closing, you don't have to be a competitive athlete to fine-tune your personalized tonic levels of dopamine and create superfluidity. For most people, setting reasonable goals and achieving them while using mindfulness meditation—and diagrammatic breathing to counteract the rush of too much dopamine—can be a winning formula for finding your own tonic levels of dopamine.

Please remember: In clinical situations, atypical dopamine levels require consulting with your medical professional or mental health provider to discuss your best treatment options.

To read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts,

- "The Neurobiology of Grace Under Pressure"

- "Superfluidity: Decoding the Enigma of Cognitive Flexibility"

- "Superfluidity: The Science and Psychology of Creating Flow"

- "Enhanced Cerebellum Connectivity Boosts Creative Capacity"

- "How Does the Vagus Nerve Convey Gut Instincts to the Brain"

- "Synchronized Brain Activity and Superfluidity Are Synonymous"

- "Living in the Limelight and the Underbelly of Superfluidity"

© 2016 Christopher Bergland. All rights reserved.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.

The Athlete's Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.