Motivation

The Long Game

How to be a long-term thinker in a short-term world.

Posted September 20, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- The pandemic has forced us into survival mode, focusing on the challenges of today at the expense of opportunities for a better tomorrow.

- Ensuring the future of organizations and personal success requires becoming a long-term strategic thinker with an execution excellence mindset.

- There is a way to break out of the endless cycle of feeling rushed, overwhelmed, and perennially behind to create a meaningful life.

- Anyone can learn to play the long game by being a long-term thinker in a short-term world.

Crash of financial stock markets, disruptions in global supply chains, online learning, working from home, shortage of hospital beds, scarcity of toilet paper—these are just some of the challenges the pandemic has posed. It has forced us into survival mode, which calls for focusing on the here and now of living. It forces us to contend with the challenges of today at the expense of opportunities for securing a better tomorrow. But ensuring a future calls for more strategic thinking. It’s necessary to become a long-term thinker in a short-term world.

There’s a real hunger for strategic thinking. In a study of 10,000 senior leaders, 97 percent said that strategic thinking is the single most important thing they can do for the future of their organization. But for many of us, we feel pulled in a million directions and simply don’t have the time or the mental bandwidth to engage in it. Working with senior leaders on how to play and win the long game in the short-term world, including as a Dean’s Fellow at the Darden Business School, I have noticed that the pandemic has made this perennial problem worse.

The Challenges of Being a Long-Term Thinker

When it comes to being a long-term thinker, there are several major challenges.

One is lack of white space—we don’t have enough room in our calendars to actually take a step back and look at the big picture. It’s not as if it requires huge amounts of time or taking a sabbatical, but it does require at least a little time away from the hurly-burly.

Another major challenge is knowing what to be optimizing for. For many of us, we’ve been in heads-down mode so long we may have lost touch with our original goals or intentions, or we may be fulfilling a script—often created by our family or by society—that isn’t right for us anymore.

A third major impediment to long-term thinking is that, like almost everything worthwhile, it usually takes way longer than we want it to, sometimes even way longer than we think it should. During the frustrating middle part, before actual results are visible, it’s easy to lose faith and assume that we’re not making any progress at all. That’s the point when a lot of people give up, often too soon.

I spoke with Dorie Clark on how one can learn to play the long game. Dorie is a recognized authority on strategic thinking. She is the author of the upcoming book The Long Game: How to Be a Long-Term Thinker in a Short-Term World. She is a keynote speaker and teaches executive education for Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business and Columbia Business School.

Playbook for the long game

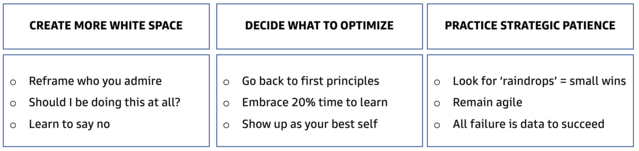

Clark’s approach has three facets: Creating more white space, deciding what to optimize for, and overcoming setbacks through the practice of strategic patience.

1. Create more white space.

In our society’s rush to success, there’s often the view that more is better. That leads to over-stuffed calendars to the point where it’s almost impossible for us ever to accomplish everything promised, leading to an endless to-do list and endless guilt. Instead, we need to be vigilant in saying no, even to good things, if they’re not aligned with our proactively set goals.

In The Long Game, Dorie tells the story of saying no to a free Caribbean vacation (she had been invited to give an expense-paid talk to a friend’s professional group) because she realized that, no matter how cool it sounded, it wasn’t strategically aligned with her own goals, and it would take a toll on her in an already heavy travel season.

2. Deciding what to optimize for.

Sometimes it’s easy to lose track of why we’re doing what we’re doing once we get enmeshed in the rat race. Clark recounts the story of Sarah, an artisanal jeweler who became an attorney in order to help small-business people and artists like herself. To help pay the bills, she took a job at a traditional law firm, where the work was all-consuming.

Over time, she came to realize that unless she made a dramatic change, she would never get to help artists through her work. So she cold-called the CEO of Etsy, then a relatively small startup, and talked her way into a job as in-house counsel. She sold him on her unique skills as a knowledgeable lawyer who also understood the mindset of the craftspeople who used the site. Sarah worked there for nine years and helped take the company public. By returning to the first principles of her legal career, Sarah was able to make a significant difference for the artists she cared about.

3. Overcoming setbacks or things taking longer than we want.

Setbacks are inevitable along the path to any meaningful goal. We know that intellectually, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy when they happen to us.

Clark reports on Anne, a treasured colleague and client of hers, who had been writing for a high-profile business publication. After six months of producing more than 35 articles for free, her editor fired her. She was told she was “not creative enough.” Not only was that incredibly insulting, but it was also demoralizing.

Anne reached out to several colleagues who also had written for high-profile publications to see how they had handled various forms of rejection. One colleague told Anne that after getting dissed by her editor, she had never written again. That stunned Anne, and she vowed she wouldn’t let the same thing happen to her. Within several months, Anne pitched and was accepted to write for an equally prestigious business publication, and several years later, she continues to write for them. We can’t afford to let gatekeepers, many of whom honestly have no idea what they’re doing, prevent us from sharing our ideas and accomplishing our goals. We have to keep moving forward, just like Anne did.

Strategic vs. Ordinary Patience

Accomplishing most of the meaningful goals of our personal and professional lives will take a while, and face detours, setbacks, and changes along the way. By its very nature, a long game requires patience, and how you view it makes a great difference. Viewing it as ordinary patience, which is typically passive—just sit back and wait, and good things will hopefully happen—is not as useful.

Instead, viewing it as strategic patience allows us to accept—reluctantly!—that we may have to wait for our goals to be accomplished. But that doesn’t mean we’re not taking action. We’re formulating our goal, creating a hypothesis about the road toward it, and monitoring it carefully to determine whether we should keep on the existing path or pivot and make changes. It’s understanding that things do take time, but we have more control and ability to effect change with persistence and perseverance than we might have imagined.

Playing the long game has the additional benefit of activating the tremendous power of compounding—resulting in what others see as overnight success.

Now that you know the playbook, you too can play the long game by being a long-term thinker in a short-term world.

References

Dorie Clark (2021). The Long Game: How to Be a Long-Term Thinker in a Short-Term World. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.