Ethics and Morality

On Becoming a Performance Consultant

Here's a checklist about necessary KSAs in being a performance consultant.

Posted November 13, 2019

Suppose you want to be a performance consultant; assisting high level performers to accomplish to their highest ability as well as enjoy the performance process. I’m talking here about practitioners who work not only with athletes but have “translated” their knowledge, skills, and abilities into doing similar kinds of work with performing artists, business executives, or those in high risk professions.

Although there are many similarities across these areas or domains, how does this understanding translate into practice? What does it take to become competent in a field—mental performance consulting—that is broad, emerging, and multiply defined?

Some formal processes and regulations establish certain external measures—yet even these are new and still being developed.

But what if you are an already-trained and skilled practitioner moving into somewhat unfamiliar territory? How do you go about measuring your competence to offer these services? What do you need to know? How do you assess what you already know? What you need to learn? How you get from “there” from “here”?

Fifteen years ago, my colleague Dr. Charles H. Brown, Jr. (known affectionately as “the other Charlie Brown”) and I laid out some of the “there” in You’re On! Consulting for Peak Performance. We’ve continued thinking, discussing, developing, and writing about the elements we consider necessary for this type of consultation.

We’ve come up with a self-assessment measure, the Performance Consulting Readiness Checklist (PCRC). This checklist and rationale form the basis for an article we’ve written, Performance Consulting Competence: A Description and Checklist. It is available from either of us: drhays@theperformingedge.com or drcharlie@headinthegame.

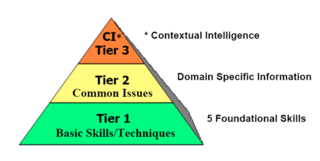

So what’s involved? Three ascending tiers of knowledge, skills, and ability (often called KSAs) plus an all-important grounding in the ethics of practice.

We describe Tier 1 as Foundational. These five areas are typically developed either in graduate school training or through subsequent formal education. The first and foremost is relationship or clinical/counseling skills. Knowing how to connect with a client is the basis (and sometimes the most important element) for assisting others. Secondly, one needs an understanding of motivation, how people change, and a positive or “growth” perspective. Because we’re talking about high-level performance, one also needs to know models of performance excellence. Physiology (the mind-body connection) is the fourth aspect, whether in relation to the obvious (such as athletes) or the sedentary (executives who direct others’ activity). And finally: performers don’t function in isolation. It is vital to understanding systemic elements, whether in relation to family, team, or organization.

The second tier relates to the particular domain in which one is practicing. What are the primary characteristics of working with athletes? With medical students? Do you find this profession interesting? Do you know the language and customs of the domain? Are there additional skills that you may need as a practitioner in that domain? For example, if you’re working with soldiers, do you know about the signs of and treatment for PTSD? If you’re working with dancers, do you know about eating disorders? Do you have a strong referral network?

The third tier is very much of an “on the job training” kind of thing. You need to have contextual intelligence (CI). CI takes into account the particular situation in which a specific consultation occurs. You may have a strong academic and research background; you may understand the performance domain in general; but ultimately you need to understand the particular individual, team, or organization as it plays out in this setting and this moment.

Performance consulting is not a fly-by-night nor pick yourself up by your bootstraps profession. Rather, various ethical principles and constraints are necessary elements to good practice—and for the protection of the public.

Within an ethical framework, here are some essential elements. First, one needs to have cultural competence. What does that mean? Having multicultural knowledge and recognition of diversity; an understanding of the particular culture of the domain(s) within which you are working; and appreciation for the historic and current differences—and any implicit power differentials—between performance consultants and some performers with whom we work. Being affiliated with—and abiding by—the ethics codes of relevant professional organizations is, likewise, critical.

How do you become competent? Documentation of your professional development is another safeguard—for you and those with whom you work. And there’s that old (milk industry) saying, “you never outgrow your need for milk.” Well, that may or may not be true, but what is true is that you never outgrow your need for professional development and supervision, consultation, or opportunities for peer review of your work.

Finally, since performance consulting is an emerging area of practice it’s important to know about and reflect on the ways in which ethics guidelines apply to particular aspects of your practice. This might involve issues such as multiple role relationships, confidentiality, informed consent, and various other elements of competent practice.

Feeling daunted? I hope not. Rather, I hope you feel energized, curious, and feeling like I’ve laid out the beginnings of a roadmap for this fascinating area of practice.