Bias

Hollywood's Regressive Stereotypes of Italians

Regressive stereotypes of Italians are harmful and hold us back.

Updated January 17, 2024 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Italian stereotypes in films like "House of Gucci" and others can be damaging for Italians.

- When Hollywood depicts Italians it often focuses on organized crime, infidelity and being short-tempered.

- Hollywood could do better, producing biopics of Italians that represent the pinnacle of Italian culture.

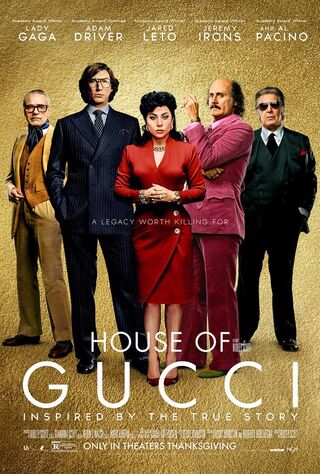

Over Thanksgiving weekend I had the chance to see House of Gucci, starring Lady Gaga, Adam Driver, and Al Pacino. The movie was definitely entertaining, and unlike other movies that use Italian culture as a backdrop to tell stories of vanity and violence (e.g., Casino, Goodfellas, and The Godfather), at least director Ridley Scott offered glimpses of the venues and motifs of Italian high culture that usually go missing in most Italian exploitation films. However, these minor concessions don't erase the fact that Hollywood, once again, traded on hackneyed, regressive stereotypes of Italians and Italian culture. Among them are the familiar tropes of Mafia culture, over-the-top gaudy couture, male infidelity, contracted murder, and last but not least, the vain, hot-tempered, power-hungry Italian woman, typified by The Real Housewives of New Jersey.

Of course, House of Gucci is based on real people and actual events, so the filmmakers can hide behind the fig leaf that they were simply bringing a true story to the big screen. But where, oh where, are the major Hollywood features about the other real people who represent the pinnacle of Italian achievement and culture? Where is the biopic about Amerigo Vespucci, for whom our country and two continents are named? Or Enrico Fermi, the nuclear physicist whose defection to the U.S. during World War II (for the safety of his Jewish wife) helped us defeat the Nazis? Or Frank Stella, the groundbreaking abstract expressionist artist, who still lives in New York City? Or Maria Montessori, the physician-turned-educator whose alternative philosophy on education spawned thousands of schools bearing her name, educating millions of children around the world, including both of my kids?

Within the realm of politics, I'm sure Democrats of Italian descent would appreciate a biopic about Nancy Pelosi, who is not only the first woman to serve as House Speaker but is also the highest-ranking Italian in the history of the U.S. government. On the other side of the aisle, I'm sure Italian Republicans would enjoy a feature film about Antonin Scalia, the first Italian Supreme Court justice.

Of course, the Italians mentioned above are merely those who have significant relevance for modern Americans. But the golden age of Italian culture—providing the world with an endless list of movers and shakers, ripe for the Hollywood treatment—was the Italian Renaissance, centered in Florence during most of the second millennium, especially the 15th and 16th centuries. The luminaries of the Italian Renaissance produced revolutionary achievements in science, literature, commerce, poetry, music, art, and architecture, but Hollywood continues to ignore them. If you've heard of Michaelangelo, Botticelli, Brunelleschi, Galileo, Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Vivaldi, Verrazzano and Nicolo Machiavelli, it is not due to them being the subject of a major American motion picture. However, I give tremendous credit to Netflix and producer Frank Spotnitz for bringing to the small screen the highlights of the Italian Renaissance in the series Medici: Masters of Florence and its sequel, Medici: The Magnificent.

If art imitates life, then Hollywood can be partially forgiven for its disproportionate representations of Italians in early films as poor, uneducated, and Mafia-connected: after all, the Italian migration of the 19th and 20th centuries disproportionately came from the rural southern Italian provinces where people were less educated and the Mafia was a major source of influence. As such, if you ask any of your Italian friends about their ancestry, they will most likely tell you their family emigrated from one of the poor southern regions, like Calabria or Sicily, not one of the wealthy, educated, cultural centers in the north, like Milan, Florence, Venice, Bologna, Genoa or even Rome. In full disclosure, my family on both sides emigrated from Calabria and Sicily, and I am a distant relative of the famous mobster Lucky Luciano.

On the flip side, life also imitates art, and thus, the continued portrayal of Italians that represent only a small slice of our culture keeps us down through the maintenance of hurtful ethnic stereotypes. Although Italian-Americans, like myself, cannot and should not claim to be the victims of oppression in America in the same way that people of color, from myriad racial and ethnic backgrounds have been victimized, the practice of cultural stereotyping still has a damaging effect on us. For many people, when Italian culture or an Italian name is referenced, the next set of assumptions usually centers on whether we're hot-tempered, "connected" (to the Mafia), or have an insatiable libido that will sooner or later lead to infidelity. We are often assumed to be tough but uneducated and sometimes given to illegal activities, like bribery and tax evasion. In other words, the Italian stereotypes that get reinforced by Hollywood contribute to attitudes among people that they can trust us to perform construction on their houses, style their hair, cook them a bowl of "pasta fazool," and help them bribe a local official, but not be their neurosurgeon, the new hire in the physics department, or the psychologist they select to treat their daughter for depression.

In closing, though I'm annoyed with United Artists and the filmmakers of House of Gucci for perpetuating regressive Italian stereotypes, in the spirit of Italian forgiveness I am willing to extend them an olive branch (or perhaps more appropriately, an olive oil dipping bowl): give me a biopic on Dr. Anthony Fauci in a few years and we'll call it even. Salud!