Attachment

How a Desire to Say “This Is Mine” Propels the Vinyl Revival

Not feeling like a digital song is “mine” drives consumers to buy and own music.

Posted November 1, 2020

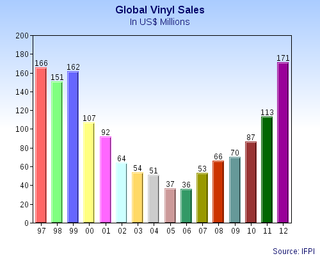

In September 2020, vinyl record sales surpassed digital CD sales for the first time since 1986. Why do so many people still want to buy and own vinyl records in an era when streaming music services are ubiquitous?

Although many audiophiles swear that analog recordings provide listeners with superior sound quality, a double-blind study (Uwins, 2015) published by the Audio Engineering Society cast doubt on the notion that listeners' perception of audio quality was propelling the so-called "vinyl revival."

Interestingly, Michael Uwins concluded that "sound quality is not the sole defining factor and other, non-auditory attributes profoundly influence listener preferences. Such [non-auditory] factors are as much a part of the vinyl experience as the music etched into the grooves."

One non-auditory factor that may be driving the vinyl revival is called psychological ownership (PO). In a seminal paper (Pierce et al., 2003), Jon Pierce and colleagues describe psychological ownership as "the state in which individuals feel as though the target of ownership or a piece of that target is theirs (i.e., 'it is mine!') and thus becomes part of one's extended self."

According to Pierce et al., when someone develops a strong emotional connection and personalized attachment to material possessions vis-à-vis psychological ownership, these tangible goods often become associated with being in a "safe place" or "home."

Many record collectors (myself included) become familiar with unique skips, scratches, and the patina of their well-worn copies of a vinyl album in ways that reinforce a sense of psychological ownership. In his paper, "Passion and Nostalgia in Generational Media Experiences," Göran Bolin of Södertörn University in Sweden writes: "It is not any version of a certain song or album, but the specific copy of a specific record (the vinyl copy with the original cover) that is the trigger of memories and emotional states."

In their 2016 paper, "Psychological Ownership and Music Streaming Consumption," Gary Sinclair and Julie Tinson explored how the shift in consumer use from physical forms of music consumption to non-material streaming services places a "greater value (emotional and monetary) on the physical product because of the lack of legal ownership and/or absence of perceived ownership associated with streaming."

Now, a new "psychological ownership" framework (Morewedge et al., 2020) helps to explain how PO may be driving the "vinyl revival" in an era of music consumption that tends to be dominated by streaming services. This paper, "Evolution of Consumption: A Psychological Ownership Framework," was published on October 22 in the Journal of Marketing.

In a news release, the authors recap their research question: "Why does—and what happens when—nothing feels like it is MINE?" Of note: The authors write MINE in all caps to emphasize that a consumer's first-person perceptions of psychological ownership are rooted in feeling that "this object is mine." As Morewedge et al. write: "Technological innovations create value for consumers and firms in many ways, but they also disrupt psychological ownership—the feeling that a thing is 'MINE.'"

Although this new psychological ownership framework doesn't focus on the vinyl revival specifically, it does address the broader technologically-driven evolution of consumption that replaces the psychological ownership of "solid" material goods.

"Psychological ownership is not legal ownership, but is, in many ways, a valuable asset for consumers and firms. It satisfies important consumer motives and is value-enhancing," first author Carey Morewedge of Boston University said in the news release. "The feeling that a good is MINE enhances how much we like the good, strengthens our attachment to it, and increases how much we think it is worth."

The loss of psychological ownership associated with using a subscription-based audio streaming service like Spotify or Pandora can leave some music listeners feeling less passionate about songs they don't "solidly" own and may help to explain the global revival of purchasing vinyl records.

Anecdotally, I know that my vinyl record collection gives me more in-the-moment happiness than any other "stuff" that I own. Listening to old vinyl records on my Hi-Fi stereo system from the early '80s evokes revitalizing memories and feels regenerative. (See "The Neuroscience of Hearing the Soundtracks of Your Life.")

As an autobiographical example of psychological ownership through the lens of vinyl records vs. streaming music: I usually experience a boost of inspiration when the 2019 cover version of "Higher Love" by Kygo featuring vocals by Whitney Houston comes on my running playlist at the gym. But I don't "own" this song; I stream it. And just like every other digital download that didn't involve going to a record store to buy, there's an emotional disconnect compared to the visceral response of playing the vinyl maxi-single version of "Higher Love" that I purchased in 1986.

Without fail, I always get goosebumps and an ecstatic feeling anytime that I put my 12" extended remix vinyl version of "Higher Love" by Steve Winwood (with Chaka Khan) on the turntable and crank it up to glass-shattering decibels on my vintage Cerwin-Vega speakers. For me, watching any vinyl record that I own spin around on a turntable (as you can see in the YouTube video above) instantly facilitates a sense of psychological ownership that streaming music will never be able to replicate.

References

Carey K. Morewedge, Ashwani Monga, Robert W. Palmatier, Suzanne B. Shu, Deborah A. Small. "Evolution of Consumption: A Psychological Ownership Framework." Journal of Marketing (First published: October 22, 2020) DOI: 10.1177%2F0022242920957007

Gary Sinclair and Julie Tinson. "Psychological Ownership and Music Streaming Consumption." Journal of Business Research (First available online: September 24, 2016) DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.002

Sarah Dawkins, Amy Wei Tian, Alexander Newman, Angela Martin. "Psychological Ownership: A Review and Research Agenda" Journal of Organizational Behavior (First published: October 12, 2015) DOI: 10.1002/job.2057

Göran Bolin. "Passion and Nostalgia in Generational Media Experiences" European Journal of Cultural Studies (First published: October 12, 2015) DOI: 10.1177%2F1367549415609327

Michael Uwins. "Analogue Hearts, Digital Minds? An Investigation into Perceptions of the Audio Quality of Vinyl." Audio Engineers Society (First published: May 05, 2015)

Jon L. Pierce, Tatiana Kostova, and Kurt T. Dirks. "Toward a Theory of Psychological Ownership in Organizations." Academy of Management Review (First available online: April 01, 2001) DOI: 10.5465/amr.2001.4378028