Stress

Scientists Discover an Elixir for Stress Called Nociceptin

Researchers have identified a natural anti-anxiety system linked to the amygdala

Posted January 9, 2014

A group of scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) in La Jolla, California collaborated with an international team to identify a system in the brain that naturally moderates the effects of stress. These revolutionary findings confirm the existence of a natural stress-damping network—known as the nociceptin system—as a potential target for therapies against anxiety disorders and other stress-related conditions. The study appears in the January 8, 2014 issue of the Journal of Neuroscience.

Marisa Roberto, associate professor in TSRI’s addiction research department, known as the Committee on the Neurobiology of Addictive Disorders, has been researching nociceptin for years. In this new study she said, “We were able to demonstrate the ability of this nociceptin anti-stress system to prevent and even reverse some of the cellular effects of acute stress in an animal mode.”

The Nociceptin/NOP System Is Linked to Stress Response in the Amygdala

Nociceptin, which is produced naturally in the brain, is part of a family of peptides that structurally resemble opioid neurotransmitters. Interestingly, nociceptin doesn’t act at all like an opioid. Nociceptin (also known as orphanin)—which was first identified in 1995—binds to its own specific receptors called NOP receptors, but it doesn’t bind well to other opioid receptors. In an unexpected twist, the scientists who discovered nociceptin in the mid-1990s found that when nociceptin is injected into the brains of mice, it doesn’t kill pain like most opioid peptides—it makes pain worse.

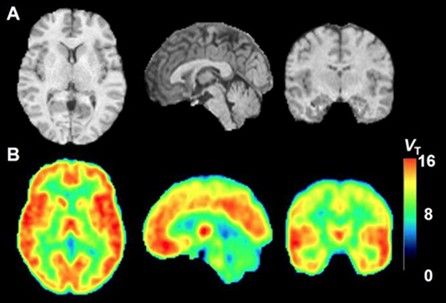

The nociceptin/NOP "anti-anxiety" system.

The molecule was given the name “nociceptive” (noci- is the Latin root for "hurt") because of its pain-producing effect. However, subsequent studies demonstrated that by simultaneously activating the NOP receptor—which is a protein involved in the regulation of numerous brain activities—that nociceptin began acting as an anti-opioid. When combined with activation of NOP it had the ability to affect pain perception, and also block the rewarding properties of opioids such as morphine and heroin.

Subsequent studies in rodents found that nociceptin acts directly in the amygdala, a part of the brain that controls basic emotional responses to stress. The findings suggested that the nociceptin/NOP system operates automatically as part of a natural stress-damping feedback response.

Researchers around the world have been collaborating to break the code of how the anti-stress properties of the nociceptin/NOP system function. This new study is a breakthrough because it might offer a better way to treat stress-related conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as help with the stress of drug-withdrawal which often derails addicts in their effort to kick a habit.

Reducing the Stress Reaction via Nociceptin and the Central Amygdala

For the new study, Marisa Roberto and her collaborators honed in on the nociceptin/NOP system in the central amygdala. Roberto and her laboratory at TSRI used a novel technique to measure the electrical activity of stress-sensitive neurons in the central amygdala.

In a previous animal study from December 2011, Roberto and her colleagues demonstrated that a particular stress peptide produced in the amygdala, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), plays a key role in the transition from alcohol use to alcohol dependence. "This peptide," said Roberto, "drives craving for alcohol." Roberto and her colleagues also demonstrated that nociceptin, can both prevent and reverse some effects of alcohol and had anti-stress benefits.

The stress-blocking effect was especially pronounced in the stressed out rats—probably due to their stress-induced increase in NOP receptors. But that was not all. By varying the sequence in which the scientists introduced the two opposing peptides, the researchers established that it did not matter whether they introduced nociceptin before or after CRF had done its work: In either case, nociceptin counteracted CRF and drove GABA levels down. "No matter when CRF is added, nociceptin wins," said Roberto.

As part of their latest study, a research colleague, biologist Roberto Ciccocioppo and his laboratory at the University of Camerino in Italy, conducted a set of behavioral experiments showing that injections of nociceptin specifically into the rat central amygdala significantly reduced anxiety-like behaviors in the stressed out rats, but showed no behavioral effect in non-stressed rats. Roberto, concludes that “stress exposure leads to an over-activation of the nociceptin/NOP system in the central amygdala, which appears to be an adaptive feedback response designed to bring the brain back towards normalcy.”

In future studies, Marisa Roberto and her colleagues hope to determine whether this nociceptin/NOP feedback system somehow becomes dysfunctional in chronic stress conditions. “I suspect that chronic stress induces changes in amygdala neurons that can contribute to the development of some anxiety disorders,” said Roberto.

Conclusion: Mindfulness Meditation and Pharmaceuticals Can Target the Anti-Stress System

The Athlete’s Way

The Athlete’s Way

Everyone needs tools and an outlet to lower anxiety and improve healthy, loving social connections. Maintaining a broad social network and close-knit intimate bonds will always be one of the most effective ways to combat depression and anxiety. Aerobic exercise, meditation, yoga and lifting weights are also very effective ways to reduce stress and break the cycle of chronic anxiety. Getting through a tough workout also builds grit and resilience.

During mindfulness training—or a physical workout—you can deconstruct the elements of what causes you stress, let out aggression, and trigger neurobiological changes that reduce anxiety. During a meditative jog, bike ride, swim, elliptical ride, yoga session, or aggressive kick-boxing session... you can break the cycle of stress both psychologically and at a neural level.

These new findings from The Scripps Research Institute are very useful because they pinpoint the neurobiological roots of our natural anti-stress system. I have written numerous Psychology Today blog posts on cognitive therapies and mindfulness practices that can reduce anxiety and help with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Please see a list of additional reading at the end of this post for direct links to those PT blog posts if you’d like to learn more.

Roberto Ciccocioppo concluded, “Compounds that mimic nociceptin by activating NOP receptors—but, unlike nociceptin, could be taken in pill form—are under development by pharmaceutical companies. Some of these appear to be safe and well tolerated in lab animals and may soon be ready for initial tests in human patients.”

Buddhist monks who do compassion meditation, also known as loving-kindness meditation, have been shown to modulate their amygdala through their practice. Increasing compassion related activity in the amygdala through meditation may reduce stress and contribute to feelings of social connectedness to the joy and suffering of other sentient beings.

Many studies have shown that various types of meditation—including LKM (loving-kindness meditation)—can reshape your brain through neurogenesis and neuroplasticy. Practicing LKM is easy. All you have to do is take a few minutes everyday to sit quietly and systematically send loving and compassionate thoughts to: 1) Family and friends. 2) Someone with whom you have tension or a conflict. 3) Strangers around the world who are suffering. 4) Self-compassion, forgiveness and self-love to yourself.

Doing this simple 4-step loving-kindness practice along with other mindfulness meditation can literally rewire your brain by engaging neural connections linked to empathy and peace of mind. Although there is no specific research or empirical data on this yet, common sense would suggest that these meditative practices might directly improve the nociceptin/NOP stress-reducing feedback system in the central amygdala.

If you’d like to read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts:

- “The Size and Connectivity of the Amygdala Predicts Anxiety”

- "Two New PTSD Treatments Offer Hope for Veterans"

- “The Neurobiology of Grace Under Pressure”

- “Mindfulness Made Simple”

- “Can Meditation Make Someone More Compassionate?”

- "Video Gaming Can Increase Brain Size and Connectivity"

- "Meditation Has the Power to Influence Your Genes"

- “The Neuroscience of Empathy”

- ”How Does Meditation Reduce Anxiety At a Neural Level?”

- “Can Mindfulness Backfire?”

- “Mindfulness Training and the Compassionate Brain”

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.