Anxiety

Why Telling Your Kids "Don't Worry!" Is a Really Bad Idea

New research explains why we worry and points to a better way to deal with it.

Posted January 7, 2020 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

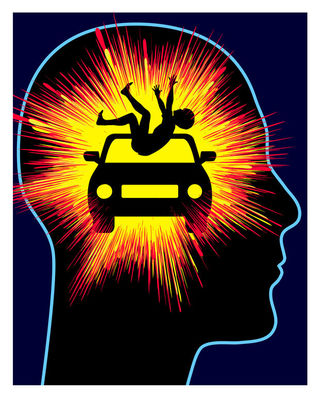

Before we tell our kids, “Don’t worry,” let’s understand why they do. Imagine sitting in algebra class, and suddenly you’re trapped in a vivid image of yourself dying in a car crash.

That image has been called “distressing future imagery,” but it can also be described as a “flash-forward.” Just like a flashback in PTSD, where a person will suddenly experience a vivid memory that can feel like it’s happening now, a “flash-forward” in generalized anxiety disorder is a vivid image of a future bad outcome—like seeing ourselves in a car crash or seeing ourselves fail in a spectacular and humiliating fashion. Worrying is an attractive but maladaptive way of managing these “flash-forward” experiences.

To date, there has been insufficient research about the origins of worry and its relationship to “flash-forward” thinking in adolescence. Innovative new research sponsored by the National Institute for Health Research in England fills this gap.

In a study of 352 secondary students ranging in age from 11-16 in the United Kingdom, researchers attempted to understand the relationship between “flash-forward” thinking and worry, between suppression as an emotional regulation strategy and unwanted, intrusive “flash-forwards,” and crucially, how these processes begin. Since adolescence is the time that many emotion-regulation strategies are generated, studying these processes at their inception can be helpful in informing treatment.

Based on regression analysis, the researchers found that “flash-forward” thinking is uniquely associated with generalized anxiety, as well as depression, but not social anxiety. The researchers also found that the tendency to use emotion suppression (trying to “push negative emotions out of the mind”) was strongly associated with the tendency to “flash-forward,” and suppression moderated the relationship between generalized anxiety and the impact of “flash-forward” images.

What Is Worry?

Worry is a maladaptive anxiety-management strategy. Because anxiety is experienced in the body, and worry is experienced cognitively, worry is a way of lowering the physical sensations of anxiety. Worry allows us to generate a certain amount of mental distance from “flash-forward” images. People with anxiety disorders report using worry to distract themselves from more distressing images.

Worry is negatively reinforced. A negative reinforcer removes something unwanted (the physical sensations of anxiety) and cements a behavior (worrying) in place. In the short term, worrying works! It lowers physical sensations of anxiety, like a pounding heart or a dry mouth, and that feels like a relief. In fact, it provides such relief, anxious adolescents tend to use it frequently. However, in the long term, it prevents emotional processing, leading to more intrusive images and greater anxiety.

What Is Emotional Suppression?

Emotional suppression involves trying very hard not to feel an emotion. Anxious adolescents try to avoid the experience of anxiety by “not thinking about it” or “shutting it off.” The problem with that strategy is that it’s impossible to shut down an unwanted emotion without also shutting down wanted ones. This is how humans work: If we aren’t feeling our fear or our anger, we also aren’t feeling our joy and our wonder.

In her book The Big Book of ACT Metaphors, psychologist Jill Stoddard uses a metaphor for emotional suppression that is called “Duct Tape Room.” (To read more from Jill Stoddard, click here.)

Imagine you are in a room. Suddenly, there is a drip on one wall. You don’t have time to deal with the drip, find the source, or fix it, so you just put some duct tape over it. For a while, that works, but eventually, another drip forms. So you duct tape over that. Before you know it, the room is a maze of duct tape, and you can’t even navigate through it. There’s just no space to live in there! Wouldn’t it be better to figure out the source of the original drip and fix it properly?

Trying to shut down an emotion also shuts down personality development, joy, and the ability to navigate the social world. It’s tempting in the moment and can sometimes be adaptive in a crisis. In the long term, it has serious side effects.

Implications for Treatment

We know that adolescence is a crucial time for developing emotion-regulation strategies, which means the best time to intervene with maladaptive strategies is also in adolescence. This study points to an important means of doing so—helping anxious or depressed adolescents learn to deal with their flash-forward thinking.

In my Targeted Parenting classes, we look at all maladaptive symptoms as potential superpowers. Flash-forward thinking can be used the same way. Instead of using “worry” or “emotion suppression” to manage flash-forwards, what if we could encourage kids to deliberately generate those images, learn from them, and move forward? In fact, “flash-forwards” can become a valuable superpower!

Gary Klein, a psychologist whose Psychology Today blog can be found here, talks about how we can use “prospective hindsight” or “pre-mortem thinking” to imagine future catastrophic scenarios and plan for them. This way, if we are ever in that situation, we’ll already have a plan in place.

Instead of allowing adolescents to suppress and try to control their “flash-forwards,” let’s teach them to actively welcome the “flash-forward,” and then use it in pre-mortem planning. If we’re picturing dying in a car crash, let’s make a checklist of everything we can do to avoid that outcome. Same if we’re picturing flunking out of school. If we’re picturing the death of a loved one—that can’t be avoided, but we can spend time with that person in the present, we can build memories, and we can remind ourselves of resources for dealing with strong emotions

Flash-forward thinking doesn’t have to be maladaptive. Let’s actively teach our children to embrace their imagery, learn from it, transform it into a superpower, and move forward. Instead of saying, “Don’t worry,” let’s teach children to embrace and transform their worries. Now, that’s what I call forward-thinking parenting.

To read more about hacking challenges into superpowers, click here.

© Robyn Koslowitz, 2020

References

Victoria Pile, Jennifer Y.F. Lau, Intrusive images of a distressing future: Links between prospective mental imagery, generalized anxiety and a tendency to suppress emotional experience in youth, Behaviour Research and Therapy, Volume 124, 2020.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103508. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005796719301949

Borkovec TD, Inz J. The nature of worry in generalized anxiety disorder: A predominance of thought activity. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1990;28:153–158.

Borkovec TD, Lyonfields JD, Wiser SL, Deihl L. The role of worrisome thinking in the suppression of cardiovascular response to phobic imagery. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;31:321–324.

S.P. Ahmed, A. Bittencourt-Hewitt, C.L. Sebastian, Neurocognitive bases of emotion regulation development in adolescence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 15 (2015), pp. 11-25.

Gross, J. Antecedent and response focused emotion regulation: Diverge consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74 (1) (1998), pp. 224-237.

Gross, J., John, O.P., Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85 (2) (2003), pp. 348-362.

Stoddard, J. A., & Afari, N. (2014). The Big Book of ACT Metaphors: A Practitioner's Guide to Experiential Exercises and Metaphors in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.