Cognition

Flapping Tongues and Brawny Brains

Does learning a second language prevent dementia?

Posted February 20, 2015

Neuroimaging studies show structural brain differences between lifelong bilinguals and monolinguals. Since bilingualism is not a choice, it’s clear that these changes in the bilingual brain are due to the experience of living with two languages.

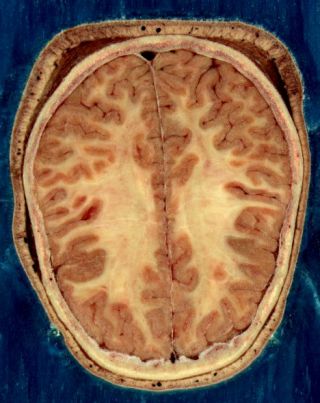

Brain tissue can be divided into gray matter and white matter. The gray matter is the tissue that performs various cognitive processes. The white matter, which forms tracts running through the brain, connects processing in one area with processing in another area. Lifelong bilinguals show increases in both gray and white matter.

It’s believed that the need to balance two languages is what accounts for these differences. In the bilingual brain, both languages are activated in any linguistic task. For example, when Russian-English bilinguals hear the spoken sequence mar-kuh, both the English word marker and the Russian word marka (postage stamp) are brought to mind.

In other words, bilinguals are constantly suppressing the language not currently being used. The ability to inhibit inappropriate responses and to direct mental resources towards appropriate responses is known as executive control, and this develops much faster in bilingual children compared with their monolingual peers.

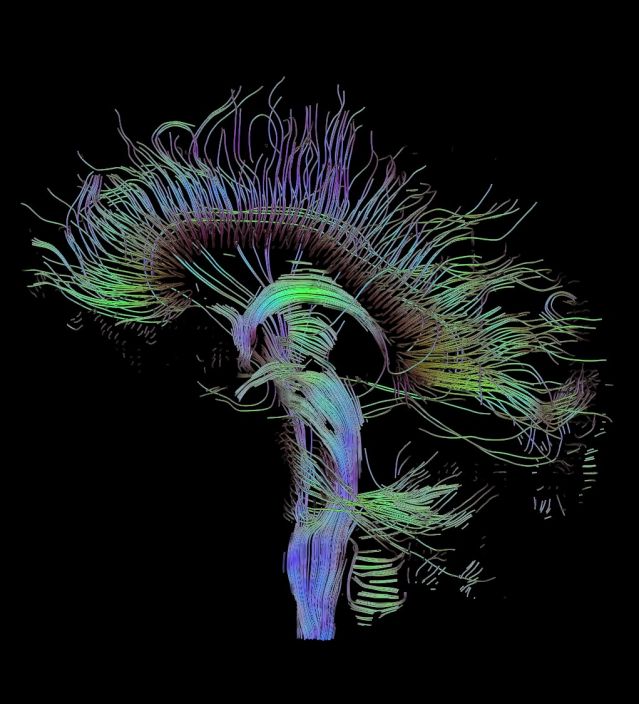

The frontal cortex, as the center for executive control, exerts its influence on other brain regions through a system of white matter tracts running front to back. Neuroimaging studies of young bilinguals show that they recruit a more diverse array of brain regions, compared with their monolingual peers, when they engage in nonverbal tasks requiring executive control. Presumably, these various regions are connected to the executive control center in the frontal lobe.

Lifelong bilingualism leads to increases in gray matter density not only in the classical language areas but also in regions involved in executive control. When compared with monolinguals, bilinguals have more gray matter density in frontal areas responsible for executive control and in parietal regions responsible for selective attention.

Not all bilinguals exhibit these enhancements of gray and white matter. Those who learned a second language later in life or never achieved full fluency have brains that resemble those of monolinguals. In other words, it’s the active use of two languages on a daily basis throughout the speaker’s lifespan that accounts for these differences in brain structure.

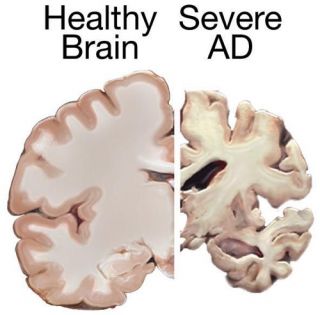

As we age, white matter tracts deteriorate and gray matter shrinks. However, older bilinguals show less reduction of white and gray matter compared with monolinguals, suggesting that living with two languages provides sufficient mental stimulation to protect against brain atrophy and dementia. This resistance to dementia is known as cognitive reserve.

Even when aging bilinguals do develop dementia, they still fare better than their monolingual peers. One study looking at clinical records found that lifelong bilingual patients were, on average, four years older than monolingual patients when symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease were first diagnosed.

Neuroimaging studies tell an even more amazing story. When the brains of bilingual and monolingual patients were studied, it was found that the bilingual brains had incurred far more atrophy than the monolingual brains. In other words, the bilinguals were still functioning at a higher level than were the monolinguals, even though they had experienced more advanced deterioration of the brain areas typically affected by Alzheimer’s disease. It’s believed that the greater white matter connectivity and increased gray matter density in other regions of the bilingual brain were compensating for the areas affected by the disease.

Lifelong bilingualism is one source of cognitive reserve, but studying a foreign language a few hours a week will provide no protection against dementia. The good news for monolinguals, though, is that there are plenty of ways you can build cognitive reserve. Playing a sport, engaging in an intellectually stimulating hobby, and interacting socially with other people—these all boost cognitive reserve just as much as living with two languages does. And they’re activities you can take up at any age.

References

Bialystok, E. (2011). Reshaping the mind: The benefits of bilingualism. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 65, 229–235.

Bialystok, E., & Barac, R. (2012). Emerging bilingualism: Dissociating advantages for metalinguistic awareness and executive control. Cognition, 122, 67–73.

Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M., & Luk, G. (2012). Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends in Cognitive Science, 16, 240–250.

Garbin, G., Sanjuan, A., Forn, C., Bustamante, J. C., Rodriguez-Pujadas, A., Belloch, B., . . . Ávila, C. (2010). Bridging language and attention: Brain basis of the impact of bilingualism on cognitive control. NeuroImage, 53, 1272–1278.

Kruchinina, O. V., Galperina, E. I., Kats, E. E., & Shepoval’nikov, A. N. (2012). Factors affecting the variability of the central mechanisms for maintaining bilingualism. Human Physiology, 38, 571–585.

Luk, G., Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I., & Grady, C. L. (2011). Lifelong bilingualism maintains white matter integrity in older adults. Journal of Neuroscience, 16, 16808–16813.

Luk, G., De Sa, E., & Bialystok, E. (2011). Is there a relation between onset age of bilingualism and enhancement of cognitive control? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 14, 588–595.

Schweizer, T. A., Ware, J., Fischer, C. E., Craik, F. I. M., & Bialystok, E. (2012). Bilingualism as a contributor to cognitive reserve: Evidence from brain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex, 48, 991–996.

David Ludden is the author of The Psychology of Language: An Integrated Approach (SAGE Publications).