Child Development

Teaching the Early Adolescent About Freedom

What kinds restrictions on and conditions for freedom nowl apply?

Posted February 6, 2017

“Since our child has already learned the basics of how to behave in the family, why as an adolescent does she have to be taught so much all over again?”

The answer is, developmental change of adolescence upsets and resets the young person’s terms of existence with herself and with the family world.

Around ages 9 – 13, the ten to twelve year process of growing up to young adulthood begins. Detaching from childhood and family the young person starts pushing for autonomy to establish more independence. Differentiating from childhood and family, the young person experiments with expression to establish more individuality. In the process, the old boundaries of childhood will be tested, and new boundaries of operation and expression will be sought.

A healthy young adolescent now wants to know two things. What old family terms of childhood conduct will continue to hold? How will new freedom for older conduct be earned? Parents need to be prepared to answer both questions.

WHAT CHILDHOOD TERMS OF CONDUCT HOLD?

Consider a few kinds of issues can be raised and may need to be re-taught.

When it comes to CHARACTER, the eager young person, by omission and commission, tries omitting the full story about what is going on for freedom’s sake. But the parental response is firm: “We continue to expect you to keep us accurately and adequately informed. HONESTY matters now as much as it ever did.”

When it comes to CONFLICT, the frustrated young person uses loud or hurtful language to get their way. But the parental response is firm: “We continue to expect you to conduct disagreement with us in a non-hurtful and respectful way. SAFETY in conflict matters now as much as it ever did.”

When it comes to CARING, the self-preoccupied young person acts less mindful of others’ needs. But the parental response is firm: “We continue to expect you to treat us in a considerate way. SENSITIVITY between us matters now as much as it ever did.”

When it comes to COMMUNICATION, the inattentive young person increasingly tunes out what parents have to say. But the parental response is firm: “We continue to expect you to LISTEN to us just as we are committed to listen to you, attending to what each other has to say.”

When it comes to COMMITMENT, the impatient young person says ‘yes’ to parents to escape further conversation and then doesn’t follow through. But the parental response is firm: “We continue to expect you to KEEP YOUR WORD just as we keep our agreements with you.”

When it comes to COOPERATION, the disinterested young person resists giving parents assistance when asked. But the parental response is firm: “We continue to expect you to HELP us when requested as we continue to expect to help you.”

When it comes to CONTRIBUTION, the engrossed young person doesn’t want to interrupt electronic entertainment to discharge some household chore. But the parental response is firm: “We continue to expect you to provide some unpaid SERVICE to help support the family just as we do.”

When the adolescent tests to see if basic childhood codes of personal and family conduct holds now that she or he is growing older, parents need to very clearly state where it still does.

HOW ARE OLDER TERMS OF CONDUCT TO BE GRANTED?

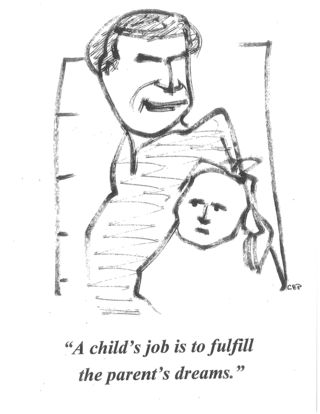

If part of adolescent change still includes acting in the family as the child was taught, another part of change, the freedom part, must also be taught. What is it that the young person can do to incline parents to give more precious freedom to grow?

The answer is: abide by the FREEDOM CONTRACT that parents need to spell out so the young person knows how more freedom can be earned. As I have stated elsewhere, it has six provisions, and it reads like this.

BELIEVABILITY: The young person is giving parents adequate and accurate information and is not lying.

PREDICTABILITY: The young person is keeping promises and agreements and is not defaulting.

RESPONSIBILITY: The young person is conscientiously abiding rules and is not in frequent violation.

MUTUALITY: The young person is living on two-way terms with parents and is not just focusing on self-satisfaction.

AVAILABILITY: The young person is willing to discuss parental concerns when they arise and is not avoiding discussion.

CIVILITY: The young person communicates with consideration and is not disrespectful.

For parents, invoking the choice/consequence connection here can be relatively straight forward. They look at the recent data. If the young person has consistently chosen to meet these conditions, the consequence is that parents are more likely to favor the next request for more freedom. Their adolescent brings a strong collaborative record to the bargaining table. “We have cause to trust you to handle additional freedom.”

If, however, data shows the young person has consistently chosen not to meet these conditions, parents are less likely to approve the next freedom request. The adolescent brings a broken record of collaboration to the bargaining table. “You start showing evidence of working with us, and we’ll be more open to considering your requests for more freedom.”

Where parental love needs to be unconditionally given, the same is not true for adolescent freedom which definitely needs to be conditionally allowed.

“Why do I still have to?” “How can I get to do?” These are two honorable questions that entry adolescents ask, and that parent need to specifically be prepared to answer. At issue are what conditions of family membership and personal conduct stay the same as in childhood and what conditions of conduct must now be met to earn more freedom to grow.

For more information about parenting adolescents, see my book, “SURVIVING YOUR CHILD’S ADOLESCENCE” (Wiley, 2013.) Information at: www.carlpickhardt.com

Next week’s entry: Helping Your Adolescent Cope with Significant Loss