Friends

When Your College Freshman Gets Homesick

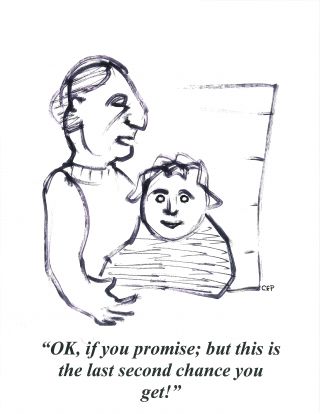

Parents can provide transitional support for an older adolescent missing home

Posted October 19, 2015

It’s actually a pretty common parental question: “What do we do when our college freshman who is living away keeps talking about 'aching' to come home?”

Homesickness is a real complaint. It is some combination of grief, anxiety, loneliness, and longing at the loss of family connections that separation from home has created. Although most common in younger children who are experiencing short term separation from family, it can also occur in last stage adolescents who have moved out for job or college and find they terribly miss the security and familiarity left behind.

When it unhappily preoccupies a young person starting college, it can significantly interfere with his or her capacity to meet demands, reach out, get involved in, and adjust to the new surroundings. If withdrawal takes over, social isolation and academic disengagement can occur, making a hard situation worse.

Although the pain of homesickness is mostly emotional, it can have bodily expression too – with suffering from tension, nausea, sleeplessness, and general feelings of bodily un-wellness. When their daughter told parents how she “aches to come home” she was speaking the physical truth.

Sources of Homesickness

Sometimes, last stage adolescents can be complicit in causing their own homesickness when, to affirm their newly won independence, they push parents away, keep them at an arm’s length, diminish communication to show it is not needed, and generally cut themselves off from the family connection they miss. Then they can even blame parents for abandoning them when it is they who are creating the painful sense of distance by pulling away.

Homesickness is not a condition to feel guilty about or to have criticized. It is simply the young person having a really tough time adjusting to the separation from home and the unease of living more independently in a new place.

Then sometimes a young person’s homesickness is actually a mask for parental child-sickness. They miss her terribly and are having a hard time letting go. So they flood her with attention, encumber her with help, and obligate her with need, all to let her know that there is no place like home, no place where she will be more welcome or better loved. In this case, the issue is not simply the young person missing home; it is parents who miss having her at home.

Then there is what I call “the curse of the happy high school.”

This is another kind of missing home that can hold young people back when adjusting to college. It’s not so much a matter of missing their biological family as missing another family -- their tight circle of close childhood friends with whom they palled around while growing through high school.

Those students for whom high school was just okay or not great fun may be glad enough when it comes time to graduate; but, ironically, those students for who high school was a triumph in every way can have a hard adjustment when they leave.

“The curse of the happy high school” can work this way. Suppose in high school you were socially prominent, were a superior student, were surrounded by a group of long standing friends, had a romantically significant boyfriend or girlfriend, and had many people who clamored for your company.

Now you have gone away to college where you are socially “no one in particular.” With conscientious effort you get average grades. You have a few acquaintances but no good friends. You have no romantic attachment, and other students show no particular interest in getting to know you. The best years of your life seem behind you. Your old friends have scattered in different directions, some moving out of touch. Your level of achievement in this larger world of competition is relatively modest. You have no social world. Dating is like starting over. And people leave you alone. What a letdown!

“In high school I was Mr. Somebody!” complained the young man. “Here I’m Mr. Nobody. Nobody knows my name. No calls! No invites! Nothing! I was really smart in high school, but here I’m barely average. I really miss how life used to be!”

So “Mr. Nobody” returns to family at the end of the semester in a funk with little desire to go back to where he counts for so little. Instead he is determined to look up all the old high school friends that remain in town, reconstitute the old group as much as possible, and resurrect the good times they had as though the past can be recovered, when it actually cannot. For some young people, letting go of high school and the high point of their life so far, can take a very long goodbye.

Growing up requires giving up, and one of the hardest parts of home life to give up is letting go the easy company and constant availability of high school friends. From what I have seen, the holding power of these groups slowly erodes away as individual members, one after another, begin to socially detach and pursue their independent trajectory in life.

Working Homesickness Through

What it takes for a young person away at college to work through homesickness, besides personal effort, is some transitional support from parents. The cell phone and computer make this connecting easy to do. Call it “electronic weaning” as the young person relies on calling, texting, emailing, and messaging with parents while adjusting to more autonomy at the outset.This transitional support allows social independence some time to grow. In these cases, the parental message needs to be: “You are not alone.” “You can call/communicate with us any time.” “We will be calling to let you know we think of you.” “You can always come back to visit.” “We admire your brave adventure of moving away.”

Having faithfully done this, by the second year a familiarity with new surroundings, comfort meeting school demands, and relationships with new friends usually take hold and attacks of homesickness become less frequent and severe. The trick for parents is to give support to help adjustment while still encouraging independence.

There are a number of common family insecurities that last stage adolescents can encounter leaving home for college, and there are some assurances parents can give that may ease this pain of missing home. I touched on five in my book, “Boomerang Kids” (2011).

“When I leave home I will be forgotten?” There is a need to know one is remembered and thought of. By commemorating special occasions and giving expressions of spontaneous caring, parents need to let the young person know she remains very present in their minds and hearts.

“When I leave home will I lose my standing in the family?” There is a need to know one’s position in the family is still secured. By preserving his room and possessions, parents need to let him know that his empty room and old belongings continue to physically hold his old place.

“When I leave home can I still come and stay?” There is a need to know one is always welcome back. By making a fuss over her visits, parents need to let her know they are glad to see her whenever they can.

“When I leave home will we still talk?” There is a need to know one is still in communication with the family. By receiving and maintaining regular communication, parents need to let him know the news about what is going on at home.

“When I leave home will you still be there if I run into trouble?” There is a need for access to mentoring support. Parents need to let her know that they are there to help figure out difficulties that may arise.

By answering these worry questions affirmatively, parents can provide assurances that encourage stepping off into more independence than the young person has known before.

Finally, most colleges have Counseling Centers staffed by people well-versed in helping a young person meet the significant challenge of creating a temporary home away from home. Recommending this short-term support is usually well to do, as is encouraging joining of student organizations to create a sense of social connection and belonging.

In most cases, homesickness resolves by the end of freshman year, so that is the parental strategy – to give support and play for delay: “Let’s keep in regular communication and wait to make any decision about leaving college until the end of the Spring Semester.”

For more about parenting adolescents, see my book, “SURVIVING YOUR CHILD’S ADOLESCENCE,” (Wiley, 2013.) Information at: www.carlpickhardt.com

Next week’s entry: How Parental Divorce can Impact Adolescence Now and Later