Chronic Pain

You’re. Not. Crazy.

Why standard medical care paradigms often fail those with chronic pain.

Posted January 30, 2020 Reviewed by Chloe Williams

In 1850, Ignaz Semmelweis presented a revolutionary idea to his medical colleagues in Vienna, Austria—one-third of the women giving birth in their care died from infections caused by the dirty, unwashed hands of physicians. Unfortunately, no one believed him, and he ended up dying in an insane asylum.

If there is one lesson we learn from history, it’s this: We do not learn from history.

How many times are diagnostic tests run on patients with chronic pain—patients with fibromyalgia, for example—that all come back “normal” or “inconclusive?” These results are then taken as permission to rule out physical causes of their complaints. With lab and imaging results in hand, the doctor looks at the patient, not knowing what to say other than, “It’s unclear what is going on. All your tests came back negative.” Even when those exact words are not said, the tone in which news like this is delivered implies that their pain does not have a physical cause, but rather a psychological one.

What is perhaps more interesting about the women giving birth in Vienna in 1850 is that they knew there was a problem. Indeed, pregnant women begged to be released from hospitals so that they could deliver at home with the help of a midwife. They knew their odds of delivering away from the hospital under a midwife's care were much better than with a physician.

Now some 170 years later, this trend towards willful compliance and acceptance of standard medical care for pain continues in modern medicine. However, it sounds something like this: “Because we cannot find the cause of your pain with an MRI or blood work, there must not be a cause for your pain.” What comes next for the men and women suffering with chronic pain is often a prescription for psychiatric medication, usually for depression.

(It’s true—being told you're crazy is depressing.)

Shedding Light on the Origins of Pain

Now in the year 2020—in the age of 10-minute medical appointments—physicians do not have (nor insist upon) the time to explain to patients how chronic pain develops. This may be due to their lack of understanding of modern neuroscience. Knowing the underlying mechanisms of chronic pain can empower both the physician and patient to view chronic pain differently.

Neuroscience is complicated. For that reason, analogies are helpful in making complex brain processes easier to understand. One analogy I use when talking with my patients about chronic pain is a motion-detecting floodlight.

Picture a deer walking through the backyard of a home, late at night. Consequently, the motion-detector floodlight turns on. Observing this, you might say to yourself, “Hey, that floodlight works!” Now picture the same scene, but this time only a single, small leaf flutters by the light. When it suddenly turns on, you think, “Oh no! That floodlight should not be turning on.”

Similarly, the way we treat chronic pain is to view pain as the problem. Traditionally, we ignore the “motion-sensitive device” in the brain causing the output of such pain. We might use medications to mask pain, but this is like trying to fix a malfunctioning floodlight by changing the lightbulb.

Pain is not the problem; the nervous system constantly producing pain is.

Understanding Pain Through a Neuroscience Lens

Light touches, different types of fabric, bed linens, a hug from a friend—these are things that should not hurt. When they do hurt, the part of our nervous system that is responsible for providing information about vibration, pressure, and touch is being misinterpreted by the central nervous system (specifically, the brain and spinal cord).

This misinterpretation comes as a threat. And when the brain assesses incoming sensory input as threatening, it then outputs protection—in the form of pain.

A basic understanding of our nervous system is immensely helpful for the treatment of chronic pain, and that begins with the knowledge of how the peripheral nervous system works. We have 43 miles of peripheral nerves whose sole function is to tell us when something is different. They do not tell us that we hurt. When we have a cut, burn, or any kind of pressure on a nerve, the nerve ending itself does not produce pain.

What it does do, is to send information to the brain about a change that has taken place. It is then up to the brain to figure out if that difference is worth paying attention to or not.

The Balance Scale in The Brain

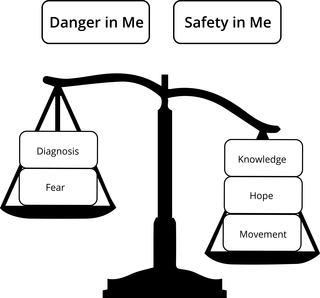

According to Lorimer Mosely and David Butler, one element of the brain’s neuromatrix map that influences the production of pain is a balance scale. On one side of the scale, the brain collects evidence of danger. It must then determine whether or not there is enough credible evidence to support the notion that the body is at risk of being harmed. If the evidence threshold is met, pain is produced.

Here are some classic pieces of evidence the brain will weigh when assessing for danger.

- “The doctor told me mine is the worse back he has ever seen!”

- “My MRI shows I have degenerative disc disease. That does not sound good.”

- “I take a lot of pain medication, but it hardly touches my pain.”

- “When I move, I hurt.”

- “My pain gets so bad that I must go to the Emergency Room.”

All of this dangerous evidence needs to be weighed against evidence for safety. Unfortunately, safety evidence is in short supply when someone has chronic pain. The brain does not know how else to view sensory information other than to treat it as a threat.

But that can change, with the right kind of help.

Evidence for Safety

Providing patients with knowledge about the nervous system is essential for changing the balance scale in the brain. The knowledge that their chronic pain may be due to an oversensitivity in the central nervous system (and, thus, not a permanent fixture in their life) provides one key piece of evidence for safety.

Over a long period of time, oversensitivity is learned. That means, it can also be unlearned. In that, there is hope. And hope for a better future is another powerful piece of evidence for safety.

While there is value in viewing pain within the balance scale theory, people with chronic pain need to experience evidence for safety in their everyday lives to be convinced. This is where learning to move, stretch, strengthen muscles, and increase endurance comes into the picture.

To help with this, a patient can experiment with a statement like, “Pain does not equal harm.” As this new thought settles in, I have heard patients say things like, “I began to tell myself that just because I hurt when I walk for five minutes, does not mean I am harming my body. Eventually, I found that I could walk for 10 minutes and only feel sore—with hardly any pain.”

As the evidence for safety begins to outweigh the evidence for danger, chronic pain begins to change. As a result, there is significantly less fear of movement and activity. As patients begin to spend more time doing what is important to them, I often hear these exact words, “I am not crazy after all!”

And that is music to my ears.