Family Dynamics

Why Do Some Siblings From Troubled Families Turn Out Fine, While Others Flounder?

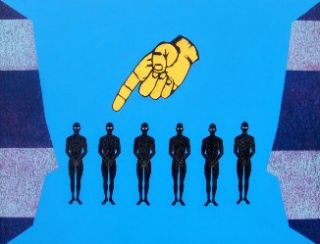

Tag, you're it!

Posted August 20, 2012

Tag, you're it

A Google search term that recently led a reader to find one of the posts on my other blog interested me. It asked, "Five children. One BPD [borderline personality disorder]. Why?"

What an excellent question!

As I pointed out in my previous post of March 5, Scientific Fraud in the Nature Versus Nurture Debate, I still occasionally hear the argument that certain behavioral disorders can not possibly be shaped primarily by dysfunctional family relationships, because other children of the same set of parents turned out to be OK.

Of course, in addition to growing up in the same household, siblings also happen to share many of the same genes — but that point is seldom brought up by people who make such claims. Anyway, neuroscientists already know for certain that complex behavior in human beings are not determined by single genes or even groups of genes.

The ridiculous assumption implicit in the sibling argument is that parents treat all of their children the same. Children are born with major differences from one another that force parents to react differently even if they try not to.

Do you have siblings? Do you have more than one child? Tell me if the siblings are all treated exactly the same by your parents or in your family. Come on, be honest.

Indirect evidence that children are responding to environmental contingincies in the family and not to genetics is also provided by a phenomenon I have occasionally seen that I call sibling substitution.

I derived this term from a similar term, symptom substitution, which is a subject that was a bone of contention between psychoanalytic therapists — who thought psychological symptoms were caused by an individual’s internal emotional conflicts — and behavior therapists — who thought that symptoms were caused by environmental rewards and punishments impacting certain behaviors.

The behaviorists claimed that if they just taught patients new and better habits and reinforced them, then they would be completely cured. The analysts said that would not work because the patient’s underlying conflict would still be present, so the patient would therefore develop a new and different symptom. The behaviorists claimed to have proof that their side won the argument, but that might be because they cured things like phobias that were not caused by internal conflicts in the first place. Neither side had any evidence for their argument when it came to dysfunctional personality traits.

What I noticed was that if I somehow successfully helped patients to significantly change a dysfunctional role that they were playing within a family of origin, they often did not develop any new dysfunctional behavior, just as the behaviorists would have predicted. Unfortunately, a previously unaffected brother or sister would suddenly step into the role they vacated! Hence, no symptom substitution. Sibling substitution. While as a patient's therapist I did not owe anything to his or her sibling, I still found this result less than satisfying. I helped a patient, but in the process I helped screw over his brother! What good is that?

To illustrate, say that one sibling is the “Chosen One” who has agreed to fulfill a dysfunctional role: He's the one who never gets married so that he remains free to never leave home - in order to keep an eye on an ailing mother after a father runs off. Let us further suppose that the Chosen One suddenly says to Mom, “I can’t do this any more. I’m moving out so I can have a life of my own. You need to find someone your own age to take care of you!” and actually moves out (Mind you, this is something most people playing such a role are highly unlikely to ever do).

If he follows through, he will usually first suffer universal condemnation from every relative he has. If that powerful family maneuver does not get him to change his mind, as it usually will, a brother may then move in with Mom and take his place. The brother may even develop marital problems that lead to a divorce so that he can free himself up to do so.

As an aside, this sequence of events might seem to indicate that all the siblings in such a family had, until this point, been perfectly willing to let one of their number stay in the unhappy position of Chosen One so they could selfishly go off and lead their own lives. However, selfishness may not be the complete reason they had stayed out of Mom's problems.

They may pressure the Chosen One to stay in the role, not just to let themselves off the hook, but because they think their mother actually prefers the Chosen One in the role, and wants no one else to play it. The Chosen One was, in a sense, picked out by Mom specifically to play the role. The Chosen One is treated by the siblings in the way they do for Mom's benefit, not just their own!

As I also mentioned in the earlier post, sometimes parents pick out some of their children to treat like Cinderellas and others to treat like princesses. So how does it happen that only one sibling among many is chosen to be and volunteers (almost always both) to be the Chosen One in a situation where a role is not determined culturally by sibling position or gender? For simplicity’s sake, lets call that person It, like in the game of tag.

Before I give my opinion on that question, I want to describe a recent journal article that attempted to look at why siblings turn out so different from one another when they allegedly grew up in the same environment.

In an article in the Journal of Personality Disorders entitled, “Psychopathology, Childhood Trauma, and Personality Traits in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and Their Sisters,” Lise Laporte, Joel Paris and others studied the sisters of female patients with BPD. They state in the abstract: "Most sisters showed little evidence of psychopathology [mental problems]. Both groups reported dysfunctional parent-child relationships and a high prevalence of childhood trauma.

Joel Paris, M.D.

True, only three of 56 sisters in the sample had the disorder themselves, and parental neglect was equally prevalent among the patients and their sisters. However, 76.8 percent of patients with BPD reported emotional abuse, while only 53.4 percent of sisters did. The severity of this type of abuse was also higher for the patients. Differences in sexual abuse were even more pronounced, with 26.8 percent of patients and only 8.9 percent of sisters reporting such abuse. In this case, however, the severity of the abuse suffered was similar.

The authors discount the idea that the dysfunctional parenting was differentially applied to the sisters in their study, despite the significant differences in some of the numbers. The sisters, they wrote, reported “equally impaired” relationship with the parents.

But this conclusion may be due to the fact that the important differences in parenting between siblings are far more subtle than studies of this type can possibly measure. The number of beatings by the father, for example, may be the same for the two girls, but what about everything else that took place in the father's separate relationships with the two daughters? Was the father nicer to one than the other at those times when he was not being abusive? What was said to each girl during the beatings? I find that details such as these are of crucial importance in understanding patients with BPD.

As I pointed out in a post on my other blog, Childhood Sexual Abuse Taken Out of Context: “Studies that examine psychological and social variables in child sexual abuse (CSA) tend to focus on factors such as who the perpetrator was, what type of abuse was suffered (penetration vs. fondling, for example), the severity and frequency of the abuse, and whether the social welfare or criminal justice system became involved. Rarely, the response of non-abusive relatives to CSA victims, usually the mother, is examined.

"Clearly, most of the victim’s interactions with perpetrators and bystanders alike occur at times when abuse is not occurring, and these other parts of such relationships may also have profound effects on the victim’s later relationships and self image. Again, due to their staggering complexity and intermittent nature, they are difficult to study using statistical techniques.

"Contextual factors include the entire history of the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator: what is said during, before, and after the abuse; what the relationship between victim and perpetrators is like when the abuse is not taking place; what other people in the family are doing at the time of the abuse and at other times; how each family member relates to the victim; who if anybody knows what is going on and whether or not they intervene; and a whole host of other characteristics of the interpersonal environment of the victim.

"Even during abuse, a victim’s interactions with a perpetrator is not limited to the sex act alone. Words may be spoken; other activities may occur right before, right after, and even simultaneously.”

These considerations are, while of vital importance, are almost impossible to quantify.

“So get to the question of why one child is singled out already,” I hear you complaining. “Why would parents focus their conflictual behavior on one or perhaps two of their children, leaving the others relatively unscathed?" OK, OK, I'll tell you why I think that happens.

In families with several children, which child or children become the primary focus of the parents’ conflicts and problems depends on a variety of factors. Certainly a child’s innate temperament plays a role, so we cannot leave genetics completely out of the equation. A parent who really does not fully want to be a parent but who feels guilty about this impulse (something commonly seen in families that produce a child with BPD), will react more problematically to an innately difficult child than to an easy child. The latter simply requires a lot less attention, while the former requires much more time.

Additionally, the problems exhibited by a difficult child may feed into a parent’s guilt over wishes to be free of family burdens. The parents may become concerned that perhaps their unacknowledged dislike for taking care of children is the cause of the child’s problems. Hence, parents who are already feeling overburdened yet guilty will often feel guiltier with difficult children. In response, they often try to overcompensate by getting more involved with those children, which may then further increase their resentment over the parenting role. The difficult temperament of the child and the internal conflict of the parents feed off of one another, leading to more family conflict and chaos, and so forth.

Another major factor which determines which child or children become “It” has to do with the natural similarities between particular children and the parents themselves, or between the children and other family members with whom the parents may have had a conflictual or problematic relationship. Parents are well known to both identify and counter-identify with their own children.

To continue with an example from an earlier post on this blog, say that the mother is the oldest sister in a traditional Chicano family and had been required to give up her social life or college as a young woman in order to take care of her younger siblings. She then grows up and has children of her own, thrusting her back into the exact same, conflictual position.

Because of identification, she might feel sorry for her oldest daughter and envious of her youngest daughter. Conversely, depending on the extent and severity of her resentment and her conflict over it, she might be harshest on the eldest daughter, who reminds her most of herself.

Either way, the manner in which she interacts with each daughter will be completely different.

In a similar fashion, light skinned vs. dark skinned children in black families may be the seed of subconscious differential treatment by parents.

Yet another major factor in one child becoming “It” is that parents may often subconsciously displace conflicted feelings about their own parents or other family members on to children who have a physical resemblance or a similar innate personality to the problem parent. That child may then become the focus of the parent’s anger, guilt, or a variety of other problematic feelings, thereby creating a special bond (be it positive or negative) with that particular child and not with any of the others.

Because of the multiplicity of factors involved, determining the exact reasons why one child is the primary focus in any particular family is a speculative and difficult endeavor. Luckily, in psychotherapy an absolutely accurate and precise identification of these factors is not necessary for planning strategies for altering dysfunctional interactions. An educated guess will usually suffice.