At the root of OCD, there are malignant and persistent forms of doubt and uncertainty: Did I really lock the door or turn off the stove? Is this person that I love and need going to be here despite my violent thoughts? If I don't wash my hands, will I be stricken with something I can't reverse?

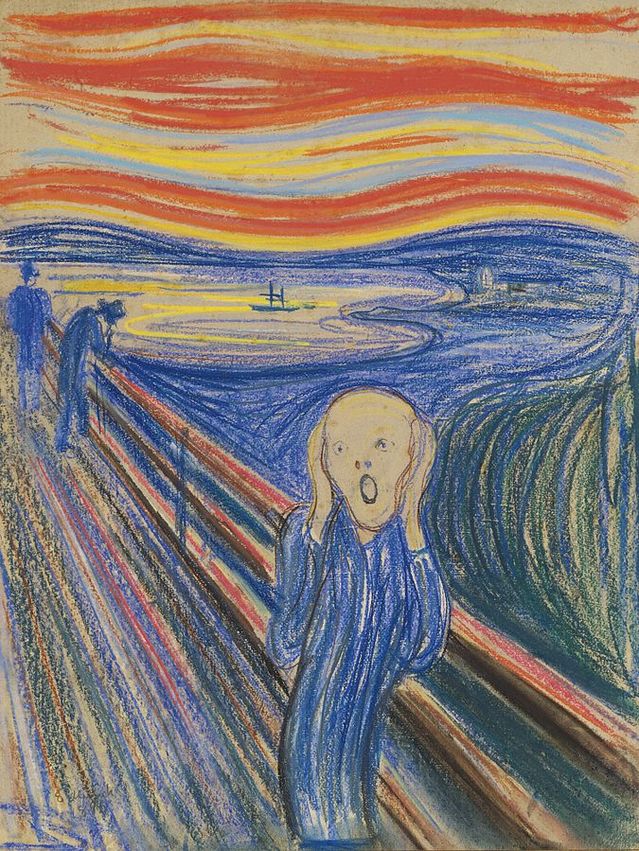

Doubt is the tinder and anxiety the fire; mundane questions quickly become a crucible. For the person with OCD, what is usually settled or solid becomes questionable, and worryingly so, such that the world begins to feel at every turn like the figure in Munch's The Scream.

The French used to call OCD 'la folie du doute', the madness of doubt, or as has often been translated 'the doubter's disease.' Like the diabolical seeds that Iago plants for Othello, doubt becomes a tormentor, imbuing the mind with a feeling of chaos and unfamiliarity, a neurotic paranoia. OCD is constant questioning, a series of only partially fulfilling rituals to help ease the fact that the world doesn't feel quite safe enough.

Largely because of this doubt, the second hallmark feature of OCD is reassurance-seeking, asking others if they think something is okay, safe, or reasonable. Do you think if I touched this subway pole that I will be okay without washing? Do you think that this person will be okay if I had a passing violent thought about them? Do you even think my feelings or thoughts make sense?

People with OCD often rely on others-like seeing-eye dogs-to help shore up their sense that their world and they themselves are stable and secure. Unfortunately, because the experience is so subjective and never a perfect fit, though people help to a certain extent their questions and doubts still linger.

Another common OCD trait is to excessively apologize to people as if one's very words or actions (or lack of action) could have the magical power to harm another person. OCD sufferers are very sensitive about harming others and exhibiting overly assertive or aggressive thoughts or actions. They are sensitive to power and its possibility to hurt and have not yet learned how to harness that inner fire to feel a consistent and contained connection to their own vital energies.

Freud believed that OCD keeps one neurotically busy with other ideas or preoccupations. These throw the person (and even the therapist) off the trail of the more central and threatening feeling. At the heart of these issues, he believed, was a great ambivalence–how can I be connected to the ones I love and be connected to myself when these issues conflict so widely?

An individual with OCD expresses this contradiction by both feeling the fear (in his/her obsessions) and not being able to truly resolve it (compulsions don't really extinguish the root of the issue). I believe that this is the case because an important part of OCD needs to be resolved not only internally but also within the imperfect and valuable sphere of relationships. What better practice than through the therapeutic relationship itself? (In a future post, I'll elaborate on how this happens in clinical practice).

OCD is fatiguing and distressing. The feelings and thoughts it summons can be terrifyingly real-though a hallmark of OCD is knowing that these thoughts are 'unlikely' or 'unreasonable'-and can make one feel as if perpetually sinking in quicksand.

We all have some obsessive-compulsive traits, as we all have to deal with the ambiguity and uncertainty of life and to contend with feeling out of control at times. For a person with OCD, this is a very painful, and debilitating daily experience, often taking significant chunks of time away from feeling safe and creatively connected to others and the world.

Therapy is extremely helpful for OCD. It can help first to feel 'not crazy' and understood from within the specific and personal framework or ones, at times, tormenting world of anxieties. It can also help to learn how to manage the intensity of one's most distressing thoughts and how to find a way of navigating the intense ambivalences of life, and ultimately how to embrace ambiguity and uncertainty in the context of creative living and relating.

OCD doesn't have to feel like a Kafkaesque tormentor. Instead, it can be a place where hope returns, as Kafka so beautifully advised:

"You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait, be quiet still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet!"