Anxiety

7 Ways to Use Anxiety to Improve Performance

Research continues to link moderate anxiety to optimal performance.

Posted December 18, 2018

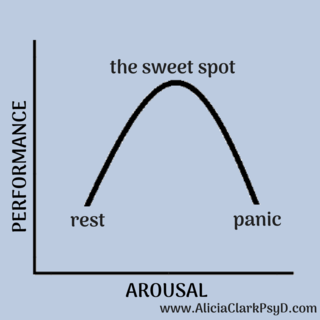

Optimal performance is something so many of us strive for in our lives, but using anxiety to get there isn’t something many of us consider, or even believe is possible. And yet the correlation between moderate stress and peak performance has been established for almost 100 years according to the Yerkses Dodson Law that was originally discovered investigating animal performance in a maze under stressful conditions.

Perhaps the most influential thinker in human optimal performance is psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who coined the term flow with the publication of his book by the same title in 1990. Flow has been described as the optimal experience of engaging in peak productivity, that combines effort, struggle, and anxiety to create necessary arousal and focus. Stress and anxiety are a key part of the flow equation, and without them, optimal performance can’t happen.

As the science of anxiety continues to evolve, more is being understood about anxiety’s role in helping protect and motivate optimal behavior, despite its common reputation for being merely a problematic symptom. Clinicians know that anxiety sufferers get better when they listen to their rational anxiety, and then use it to do something about the problems it routinely signals.

Assembling the science supporting anxiety’s role in driving optimal performance has been among the more rewarding parts of writing my new book, Hack Your Anxiety (Sourcebooks, 2018). Far from just an annoying symptom, moderate anxiety can be a valuable tool in helping us achieve our best selves.

While there is much still to learn, there are already key takeaways for how we can use this emerging science to our advantage. Here are 7 science-based strategies to use anxiety to improve performance.

- Change your attitude about anxiety, and embrace it as a resource for good. A large-scale study of stress and its impact on health demonstrated that stress is only harmful when we believe it is, even when it is severe. Believing you can handle stress and anxiety, even if it is intense, protects against doubt and the negative spiral that can come from fearing anxiety.

- Optimize focus. According to science, one of the most powerful things anxiety does is harness focus, and redirect attention where it’s needed most. With so many competing demands for our attention, and the targeted effort it takes to focus, anxiety can give us the boost we need to step up our performance.

- Anxiety is a natural motivator. Stress stimulates dopamine that fuels the 'motivation to act.’ Anxiety is seldom praised for its reflexive energy for action, but it has long been associated with a drive to do something. Even Webster’s defines anxiety is a “fear or nervousness about what might happen” along with “a feeling of wanting to do something very much.”

- Anxiety keeps you alert, vigilant, and ready for optimal performance. Not only does anxiety keep you motivated, it may help you be more efficient in your actions. Research from France suggests that stress allows for efficient detection of threats, along with swift action. Neural processing is fast and selective in sensory and motor systems, allowing for peak efficiency in processing and responding to stimuli.

- Anxiety reminds you of things you’ve forgotten, things that need attention. Anxiety errs on the side of caution (thanks to its negativity bias) and can even overgeneralize and exaggerate potential risk. While this isn’t a comfortable experience to envision the worst, avoiding an unwanted outcome can give us the jolt we need to stay on task.

- Reappraise any performance anxiety as excitement. The latest science of emotion suggests that emotions are constructions we actively participate in creating. We feel a sensation, run it passed our experiences and vocabulary, and in choosing a label, actually construct the emotion we experience. In studying the impact of reappraisal on anxiety, Alison Brooks at Harvard took this concept of emotional construction a step further. She found that participants who simply reappraised their performance anxiety as excitement felt significantly less distress than those who did not.

- Prioritize sleep when you can. Research continuously demonstrates the power of sleep to help us function at our best - our brains need it to flush toxins and absorb new information. Stress and anxiety work best in our life when they are balanced by rest, and not enough sleep can exacerbate anxiety symptoms. Aim for 7–9 hours nightly when striving to perform your best.

Allowing anxiety to fuel optimal performance means accepting you will take an active role: do what is needed, make things happen, and know you can handle how you feel along the way. Anxiety doesn’t have to be the enemy if you can view it as a motivator for growth and change.

Peak performance and optimal experience require we bring our best effort, and harnessing our anxiety can help us do just that.

This post originally published on Dr. Clark's blog.

©Alicia H. Clark, PsyD

References

Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, 68.

Zein, M. E., Wyart, V., & Grèzes, J. (2015). Anxiety dissociates the adaptive functions of sensory and motor response enhancements to social threats. ELife,4. doi:10.7554/elife.10274

Barrett, L. F. (2013). Psychological Construction: The Darwinian Approach to the Science of Emotion. Emotion Review,5(4), 379-389. doi:10.1177/1754073913489753

Brooks, A. W. (2014). Get excited: Reappraising pre-performance anxiety as excitement with minimal cues. PsycEXTRA Dataset. doi:10.1037/e578192014-321

Öhman, A., Flykt, A., & Esteves, F. (2001). Emotion drives attention: Detecting the snake in the grass. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General,130(3), 466-478. doi:10.1037//0096-3445.130.3.466

Aston-Jones, G., & Cohen, J. D. (2005). AN INTEGRATIVE THEORY OF LOCUS COERULEUS-NOREPINEPHRINE FUNCTION: Adaptive Gain and Optimal Performance. Annual Review of Neuroscience,28(1), 403-450. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709

Keller, A., Litzelman, K., Wisk, L. E., Maddox, T., Cheng, E. R., Creswell, P. D., & Witt, W. P. (2012). Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. Health Psychology,31(5), 677-684. doi:10.1037/a0026743.