Coronavirus Disease 2019

Grandma Won't Die...This Year

Statistics keep the flu away and predict me to be alive at 101.

Posted September 4, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

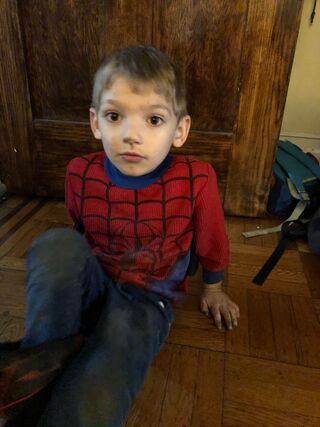

“You’re going to die,” my youngest grandson told me, with a matter-of-fact voice, as if he had just learned something and he thought I should know it too.

“Yes, but not for a long time,” I answered.

My four daughters are not so blunt, but they worry. They urged me to take precautions to prevent COVID. In March, I promised that I would not get the virus until October, when the medical professionals would know how to treat it. In April, I often checked my pulse, fever, and oxygen, grateful to keep my promise.

It is now September. I was right. The death rate for people hospitalized with COVID-19 is about half what it was in early spring. Doctors try to avoid ventilators and nurses put people on their stomachs to breathe; scientists know which drugs might help (vitamin D) and which do not (hydroxychloroquine).

I am more relaxed about washing groceries and checking my vitals. I am also more vigilant about mask-wearing and distancing, because I, like the doctors, have learned. A revised promise: I will never get the virus, not even in October, because I now know about long-term cardiovascular and neurological damage.

My daughters have a new worry. They have read about a second spike when flu season starts. I need to teach them about statistics.

First, overall: The United Nations (World Population Prospects, 2019) reports that the average U.S. woman dies at age 81. I am 78; almost there. But 81 is an average. It includes babies who die of SIDS, children killed by cars, teenage girls with illegal abortions, adult women with cancer, heart disease, diabetes.

The U.N. statistic that relates to me is that, if a U.S. woman is alive and well at age 80, she will live, on average, 10.16 more years. That puts me to 90. And research by Zaniotto’s team (in Scientific Reports, 2019) on old people in the United States and England finds that those without four deadly behavioral risks (smoking, obesity, alcohol, inactivity) live an additional 11 disability-free years.

That means I am likely to live, happy and vital, to 101.

No guarantees. I could be hit by a bus tomorrow, or be struck by lightning, or be bitten by a poisonous snake. But back to statistics: Those deaths are highly unlikely. Motor vehicle fatalities are usually young children or older adolescents. Children dart into the street or refuse to stay in the car seats; novice drivers take foolish risks when they are with friends.

That is not me: I don’t dart, I wear my seat belt; I no longer drink and drive. Less than one North American in 100,000 dies of lightning or snakes, and that one is usually a young, foolish, man. No old woman dies of lightning or snakes.

My daughters raise another specter, the flu. Trump was two decades off when he dated the 1918 epidemic, and he underestimated COVID-19. In March he tweeted “Last year 37,000 Americans died of the common flu. It averages 27,000 to 71,000 deaths per year. Nothing is shut down, life and the economy go on. At the moment there are 546 confirmed cases of coronavirus, with 22 deaths. Think about that.”

Wrong, as Trump now knows. But not completely wrong. Flu is deadly. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that flu caused about 41,000 deaths in the winter of 2019-2020. The number is approximate because lab tests confirmed only 11,199 of those deaths. The others were what the CDC calls influenza-like illnesses (ILL), defined as acute respiratory illnesses with a fever above 100 F and onset within the past 10 days (to distinguish it from chronic lung disease).

So yes, I could die of the flu, as about 15,000 old women did last year. But consider the data again: I got my flu shot, the extra strong one they recommend for people over age 65 whose immune system might be waning. Vaccination might not prevent infection, but it reduces severity: no hospital, no death. I protect my immunity by getting enough sleep (at least 7 hours) and eating lots of yogurt. (Probiotics help, according to Lenoir-Wijnkoop and her colleagues, in Nature, 2019.)

But there is a more substantive reason why the flu won’t kill me this year: It might kill no one! In Science, August 2020, Kelly Servick described the “flu season that wasn’t." Almost no flu occurred in nations below the equator, which have just experienced winter, their usual flu season.

Cases of flu 2019 2020

Argentina 4623 53

Chile 5007 12

Australia 9933 33

South Africa 1094 6

Those are cases, not deaths. Those countries had social distancing, lockdowns, mask-mandates, and hand-washing advisories, all winter long (our summer).

What does that mean for me? As long as I continue to wash my hands, avoid closed and crowded rooms, and don’t kiss my grandchildren, I won’t get the flu this year. Non-kissing is hard, but I can kiss people when I am 80, and in the 11,512 weeks after that.

Maybe by then my grandson will know not to tell me that I am going to die, and maybe by then I will tell him that I am glad I saw him grow up. Then, not now, I will be ready to say goodbye.