"Nothing could be more mistaken than the now fashionable attempt to apply the methods and concepts of the natural sciences to the solution of social problems." - Ludwig von Mises, Omnipotent Government

The 1990s may have been dubbed “the Decade of the Brain,” but the past ten years has seen an explosion in popularity of the field of neuroscience. Every week, it seems, a new popular book is published which promises to explain the age-old mysteries of human existence in terms of brain science. The age of neuroscience is upon us; to the believers, it is only a matter of time before all human problems will be understood--and conquered--through an understanding of the brain.

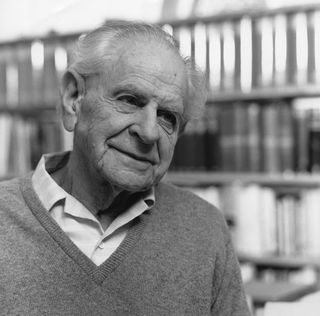

The great philosopher of science Karl Popper defined scientism as the inappropriate application of the scientific method to questions beyond the scope of science, such as philosophy, ethics, and psychology. While science is very good at telling us the boiling point of water, it is utterly useless in giving us meaning in life, answering questions of morality, and explaining human thought. Nevertheless, pop neuroscience has attempted to do all of these things, and more.

Why is an understanding of the physical brain insufficient in answering some of humanity's greatest questions? Because it rests on a faulty biological reductionism that sees man as no more than a machine, a helpless computer-brain at the mercy of neurons and brain chemistry. The philosophical concept of "self" (or "mind") is erroneously equated to brain. This reductionistic misapplication of knowledge ascribes scientific answers to nonscientific questions, ignores differences between persons, and negates explanations of human conduct in terms of freedom and will. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) might show us that certain areas of the brain "light up" when people do or think certain things, but it can never tell us why a person thinks, feels, or does what he does. To believe otherwise is the height of scientistic folly.

The application of neuroscience to the practice of psychotherapy is especially troubling. I recently saw an elderly lady in psychotherapy who fell depressed after the death of her husband of sixty-plus years. Her husband was not only her spouse but her confidant, her closest friend, and the only man she ever loved. No explanation of her depression in terms of neuroscience could possibly suffice in conceptualizing her melancholic emotional state. What she needed was not some biochemical explanation of her emotional suffering but rather human connection, understanding, and empathy.

Psychiatry--and by extension psychology and psychotherapy--would be wise to leave the brain science to the neurologists and focus instead on the insightful understanding of individuals as moral agents and human actors.